Part 1—InterTribal Buffalo Council Restores Herds—and More

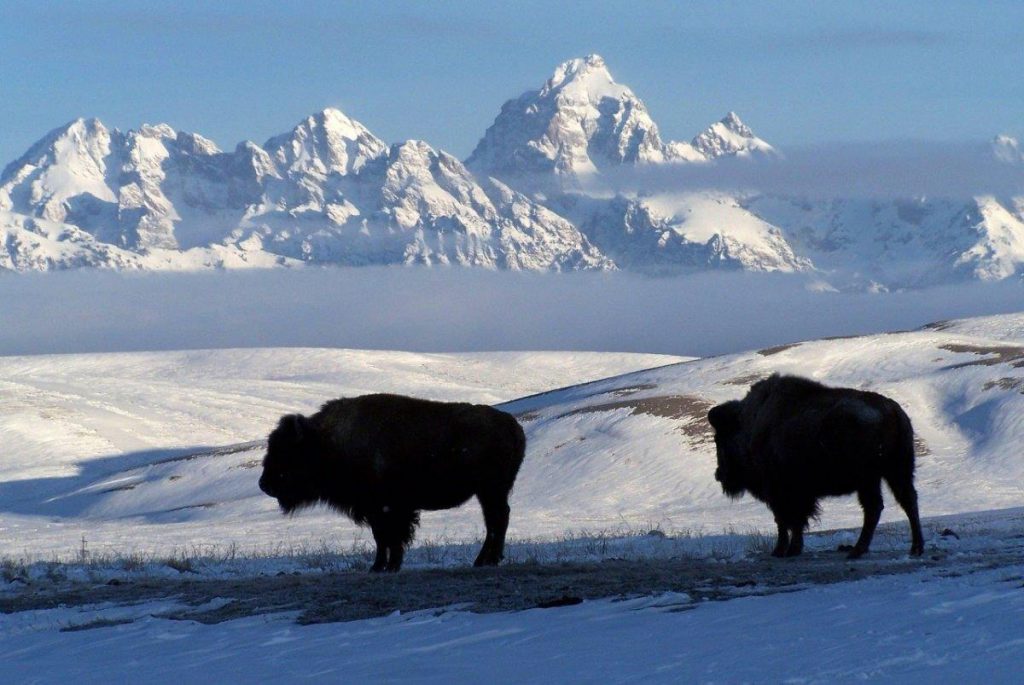

Whether it is unique training opportunities, large scale restoration goals, more effective marketing or Native cultural issues, ITBC has worked with tribes to restore buffalo on tribal lands. Photo ITBC.

Over and over delegates testify: As we bring the buffalo back to health, we also bring our own people back to health. And that’s what it’s all about.

In February 1991, a meeting in the Black Hills of South Dakota, hosted by the Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, brought Native people from all four directions, as is traditional, to talk about a topic that concerned them all.

How can Indian tribes with experience raising buffalo help other tribes restore buffalo to their lands? Why is this important to us?

Representatives of each of 19 tribes—most of them from the Plains states—spoke of their desire to obtain or expand buffalo herds and grow them into successful, self-sufficient programs.

Many difficult and complex problems were involved that tribes and herd managers had faced alone—with mixed results.

Each tribe that desired buffalo needed to purchase or set aside enough suitable lands for year-around grazing or hay lands, fence that land with high, sturdy fences, and obtain buffalo—all expensive options.

Not all tribal members agreed with the value of such land use.

Next, they needed to manage the herd wisely, so if possible, the buffalo herd would be financially self-sufficient.

Growing the herd, with a healthy calf crop each year—so they produced enough meat for tribal and ceremonial uses and young stock for sale or expansion—was essential.

Furthermore, far beyond the economics of it, most buffalo enthusiasts expressed concerns that they inspire others—not merely to restore live buffalo to tribally-owned pastures across the United States—but that they restore them in ways compatible with their traditional spiritual and cultural beliefs.

Although some tribes and tribal members had engaged in production of buffalo for sale and/or for subsistence and cultural use, these activities were conducted by each individual tribe, with little or no collaboration between tribes.

Frequent droughts on the Plains brought unexpected set-backs.

Some managers were able to fill some needs, and not others. Some herds dwindled and ended. Many managers became discouraged at the high costs and seemingly slight benefits.

Yet, others succeeded well.

As the meeting ended, all representatives knew they wanted to continue the discussion and find ways to work together to help each other.

It was plain to all that an organization to assist tribes with their buffalo programs was sorely needed.

With hard work and dedication of the group, the US Congress was approached with the need to appropriate funding for tribal buffalo programs. That June, in 1991, Congress voted to provide funding and donate surplus buffalo from national parks and public refuges to interested tribes.

This action offered renewed hope that the sacred relationship between Indian people and the buffalo might not only be saved but would in time flourish.

The intertribal group agreed to supervise federal grants and distribution of the animals.

Buffalo began coming home to reservations in earnest.

The Tribes again met in December 1991 to discuss how the Federal appropriations would be spent.

At this meeting, each tribe spoke of their plans and desires for buffalo herds and how to help existing tribal herds expand and develop into successful, self-sufficient programs.

In April of 1992 tribal representatives gathered in Albuquerque, NM.

It was at that meeting that the InterTribal Buffalo Council (initially called the InterTribal Bison Cooperative—ITBC)—officially became a recognized tribal organization. Officers were elected and began developing criteria for membership, articles of incorporation and by-laws.

In September of 1992, ITBC was incorporated in the state of Colorado and that summer established a permanent office in Rapid City, South Dakota.

“Having the buffalo back helps rejuvenate the culture,” says Jim Stone, Rapid City, Executive Secretary of the Intertribal Buffalo Council and a Yankton Lakota.

“In my tribe, like others, the buffalo was honored through ceremony and songs. There were buffalo hunts and prayers to give thanks to the buffalo.”

The council has adopted the mission of “Restoring buffalo to Indian Country, to preserve our historical, cultural and traditional and spiritual relationship for future generations.”

Thirty years of Tribal Buffalo Progress

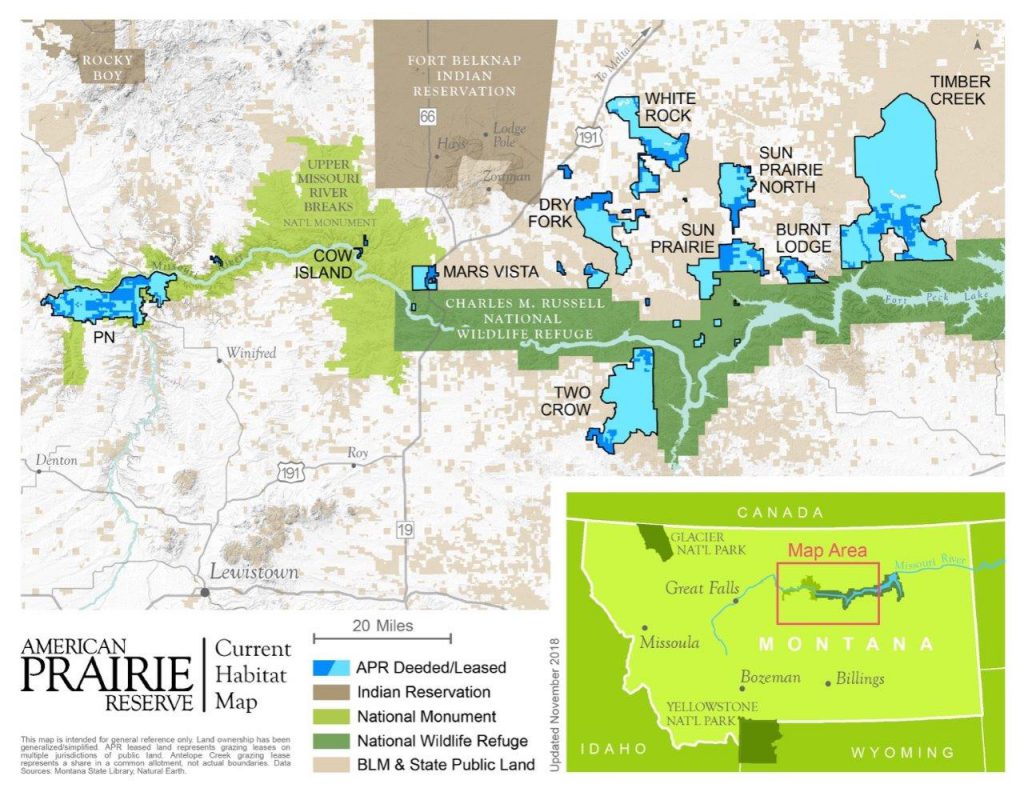

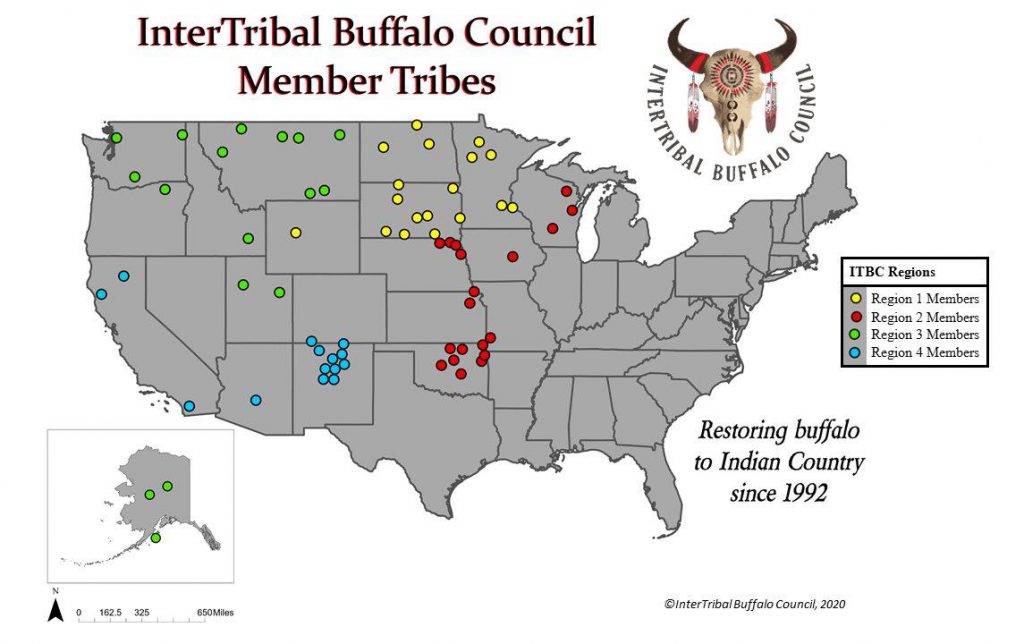

Today, 30 years later, 69 federally recognized Tribes from 19 states have joined the Intertribal Buffalo Council. Most of these tribes own a buffalo herd, for a total of more than 20,000 buffalo living in tribal herds across the United States today.

Sixty-nine Tribes with ITBC herds in 19 states are divided into 4 regions with over 20,000 buffalo—most are west of the Mississippi River. ITBC.

InterTribal Buffalo Council Member Tribes

|

|

ITBC is committed to helping each tribe bring buffalo herds on Indian lands in a manner that promotes cultural enhancement, spiritual revitalization, ecological restoration and economic development.

Many are Plains tribes with a long history of dependence on buffalo for food, shelter and clothing.

Others have no known history of hunting buffalo, but desire the cultural experience.

“Today’s resurgence of buffalo on Tribal lands, largely through the efforts of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, signifies the survival of the revered buffalo culture as well as survival of American Indians and their culture,” says Ervin Carlson, Blackfeet, President of ITBC.

Ervin Carlson, president of ITBC, member of the Blackfeet tribe in northwestern Montana, recently stated their goal this way:

“For Indian Tribes, the restoration of buffalo to Tribal lands signifies much more than simply conservation of the national mammal.

“Tribes enter buffalo restoration efforts to counteract the near extinction of buffalo that was analogous to the tragic history of American Indians in this country.” In other words, they see the two tragic events as similar and parallel to each other.

“Today’s resurgence of buffalo on Tribal lands, largely through the efforts of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, signifies the survival of the revered buffalo culture as well as survival of American Indians and their culture.”

“We have many cultural connections to the buffalo,” says Alvah Quinn, a Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate from South Dakota, former manager of the tribal buffalo program.

“I grew up hearing about the buffalo, but we didn’t have any around on the reservation.’

His tribe’s last recorded buffalo hunt was in 1879.

Quinn says he will always remember the night in September 1992 when he helped bring the first 40 buffalo to his home reservation.

“I was really surprised that night. There were 60 tribal members waiting in the cold and rain to welcome the buffalo back home. After a 112-year absence!”

They now own 350 buffalo—one of many success stories.

After three decades, Intertribal Council leaders are even more convinced of the value of these buffalo herds.

Daily they are reminded that buffalo represent the spirit of native people and how their lives were once lived, free and in harmony with nature.

They’ve seen how bringing buffalo back to tribal lands helps to heal the spirit of Indian people.

Today some tribes own very large buffalo herds, for commercial as well as cultural purposes.

The Crow Tribe has 2,000 buffalo running free-range on their large, mountainous reservation spanning the state line between Billings, Montana, and Sheridan, Wyoming.

Pauline Small on horseback, carries the flag of the Crow Tribe of Montana. As a tribal official, she is entitled to carry the flag during the Crow Fair parade at Crow Agency, south of Billings, Montana. The Crow have one of the largest tribal herds, at 2,000 head.

At Pine Ridge, the Oglala Sioux raise 1,100 including both tribal and college buffalo herds, and Rosebud also raises 300 under a tribal umbrella, reports Stone.

Other tribes set goals for a small herd mostly for cultural and educational purposes, explains Mike Faith, long-time tribal buffalo manager and now tribal chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, who also serves as Vice President of the Executive Council of the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

Mike Faith, Vice President of ITBC, Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman and long-term manager of the tribal buffalo herd, advises “Quality over quantity is what counts.” ITBC.

Faith has worked with the InterTribal group since its beginnings. He says a new tribe might slaughter only one or two buffalo a year for special celebrations and ceremonial use.

It depends on land available, land uses on the reservation, tribal population and historic dependence on buffalo.

“Quality over quantity is what counts,” says Faith. “Whether they want a small herd—20 or 30—or a larger commercial herd, we can give help and technical assistance.”

No matter the numbers, Faith suggests it is important that new tribes take their buffalo venture seriously. Hiring a knowledgeable buffalo manager is critical.

The Intertribal Council offers training and educational programs and coordinates transfer of buffalo and grant funds.

Troy Heinert, ITBC Range Technician, visits Rosebud, SD, helping Wayne Frederick and his crew work 2014 surplus bison “on hold” so they can be released out into the pasture. ITBC, Facebook, October 31, 2014.

Experts are available to help tribal leaders work out management and marketing plans that fit their particular concerns and goals, if desired.

Details like building high, strong fences before the buffalo arrive are essential—and costly.

Big bulls can jump six feet or more.

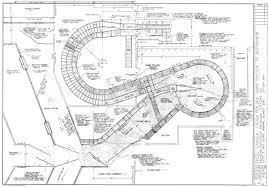

Round or angled corrals work better than square, as buffalo tend to jump when they hit a corner.

They may get hung up and die of a heart attack.

Corrals work best when built with sorting tubs and alleyways with enclosed sides so animals move ahead without seeing out. Curved alleyways are helpful so buffalo think moving ahead is a way to escape.

There may be grants available to help defray costs, the experts tell the tribes.

A buffalo herd needs plenty of space, grass and water. On request, experienced leaders will visit to help determine goals and advise on land base.

Sometimes they recommend reducing animal numbers to better accommodate the land available.

They also work with federal agencies to help bring fractured lands together.

A manager with training in low-stress buffalo handling is preferred.

Handlers familiar with raising cattle will find surprising differences, Faith explains.

For instance, many cowboys shout at their cattle when chasing them.

But buffalo are essentially wild animals, he says. They feel stressed with noise and pressure, so it’s better to move them quietly and slowly.

Arnell D. Abold, of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) Tribe, was recently appointed to the position of the Executive Director for the InterTribal Buffalo Council. Ms Abold is the first Native woman to serve as Director of ITBC since its inception in 1992.

Arnell D. Abold, of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) Tribe, serves as Executive Director for the InterTribal Buffalo Council. The first Native woman Director of ITBC since its inception in 1992, she has served as its Fiscal Director since Nov. 2001. ITBC.

Ms. Abold previously served as the Fiscal Director. She continues to devote her career to the vision and the mission of the organization.

Her passion, belief, and devotion to the buffalo and the membership tribes that hold the buffalo sacred is what drives her dedication and loyalty to the organization.

Tribal Buffalo Success Stories

One of the first tribes to raise buffalo, the Taos Pueblo, in northern New Mexico in the valley of a small tributary of the Rio Grande, obtained them in 1902 or 1903 from the Goodnight herd, according to Jim Stone, of the ITBC.

The Salish-Kootenae had buffalo too, perhaps descended from the original calves brought by Samuel Walking Coyote to the Montana Flathead reservation.

On South Dakota Indian reservations, the Pete Dupree and Scotty Philip families continuously raised buffalo from the wild in the 1880s.

Some early private buffalo herds did not survive long or were removed during the brucellosis eradication program, says Stone.

Most replacement buffalo now come from the federal park system and have been disease-free for decades.

The Yakama herd grew from 12 buffalo in 1991 to more than 200, producing 40 to 50 calves every year. The tribe, located in south central Washington on the Columbia Plateau, hopes to expand its buffalo herd to 400 over the next few years, and furnish more meat for tribal elders and low-income families.

Eventually the Stillaguamish Tribe near Arlington, Washington plans to share buffalo meat with neighboring tribes and make it available to the general public.

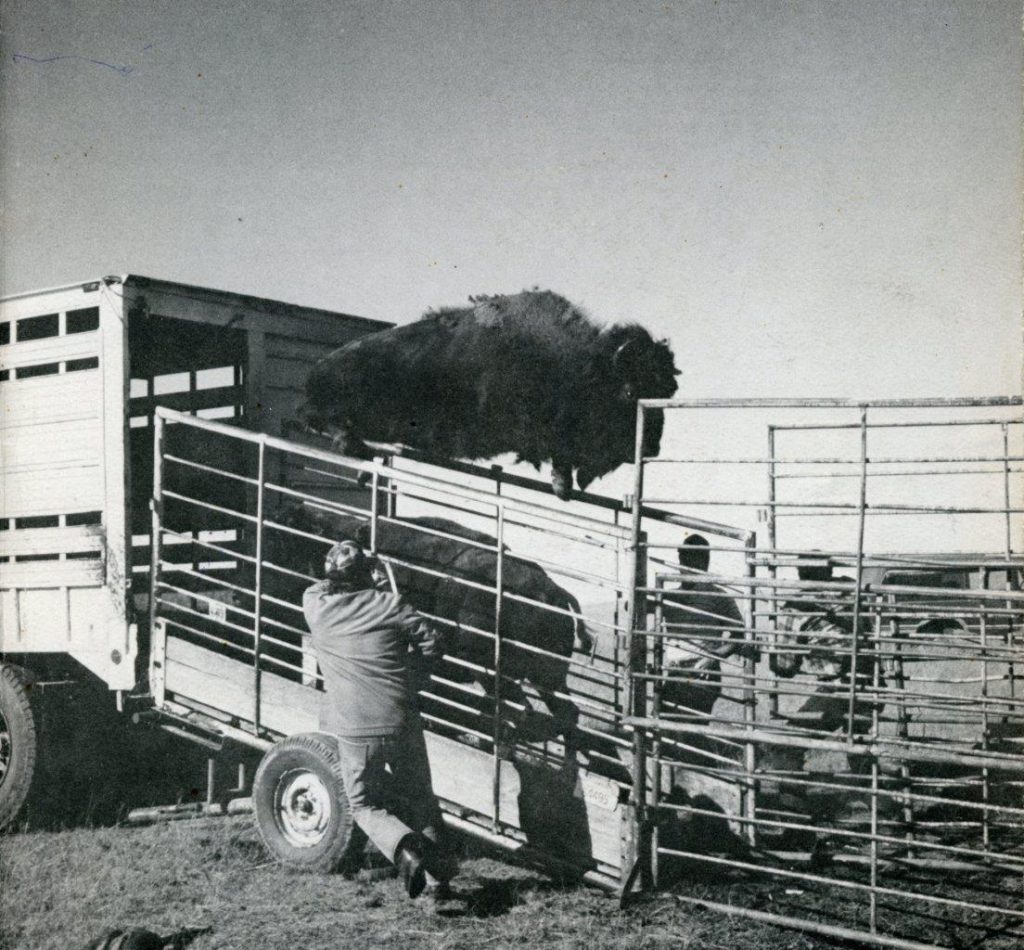

ITBC Buffalo herd arrives at new home in Montana. Photo fwp.mt.gov.

In 1997, the Oneida Tribe of Wisconsin started their buffalo herd with 13 heifers and a bull from Wind Cave National Park.

When she saw the delighted response of Native People on western reservations to the return of buffalo, Pat Cornelius, now Oneida herd manager and former board member of the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, felt sure her people would be heartened as well by a herd of their own.

She describes the arrival of the first 14 buffalo as an awesome spiritual moment.

“The earth shook!” she said, when the animals jumped from trucks.

By 2007, the Oneidas owned 120 cows and bulls, with 43 calves.

The presence of buffalo has made a big difference to them, Cornelius says, describing the many local people visiting daily in summer and winter from a specially-built viewing mound and shelter.

The Eight Northern Pueblo tribes of New Mexico, like many other Native Americans, live on the land of their ancestors. Five maintain buffalo herds and cooperate to diversify bloodlines.

The Picurís herd began over a decade ago with one female and one bull. It has grown to 80 head, not including spring calves.

Their buffalo are pastured in a field close to the road, so visitors often stop.

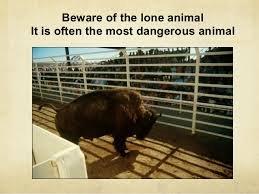

Tribal herd manager Danny Sam cautions them that it is not safe to walk among the buffalo.

Sam serves as secretary for the Intertribal Buffalo Council and has been involved with the program since the beginning.

He has seen many changes. One he does not care for is that federal inspections, taken over from the state, require more paperwork, charge a fee and classify buffalo as an exotic species, rather than livestock.

“They’re not an exotic species,” Sam says. “They’re native to this country.”

New Bison Herds in Alaska

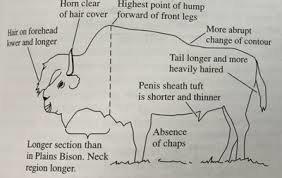

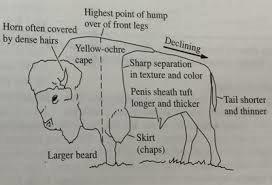

Alaska may not seem like a natural home for buffalo. But bones and petroglyphs prove the larger wood buffalo lived and were hunted there in ancient times.

The first Alaskan group to join the restoration program, after Athabascan tribes began introducing plains buffalo, was at Stevens Village near Delta Junction.

The new herd there includes 38 buffalo, 14 of them calves, obtained with help from the Intertribal Buffalo Council.

Rocky Afraid of Hawk, a Lakota Oyate elder and the Council’s spiritual advisor, flew to Alaska from South Dakota for a welcoming ceremony.

He told the Athabascan people that buffalo were placed on earth to teach people how to live.

“You can learn from them.” he said.

Afraid of Hawk presented the village with a buffalo skull to use in ceremonials and prayers. To bless the event, he burned sagebrush in a metal can with coals from the fire.

Randy Mayo, first chief of the Stevens Village tribal council, carried the smoldering sage to guests and let them wave smoke over their faces.

The village presented Afraid of Hawk with tobacco and salmon strips.

Traditional chief David Salmon, a Chalkyitsik elder, sat on a folding chair beside a wood fire, relating buffalo stories told by his grandfather.

Beside him, Herb George, a Stevens Village tribal council member, stirred a bubbling soup made with buffalo meat.

He said he was making soup the way his father taught him—like a traditional potlatch soup, but with buffalo bones instead of moose.

Mayo believes being around the buffalo can help people work through their problems.

He acknowledged that when the village voted to move forward with raising buffalo, he didn’t know much about the animal that had provided food, clothing and shelter to his ancestors.

He has learned a lot.

“Every time I come here it lifts me up,” said Mayo. “Just observing them, you never get tired of it.”

Stevens Village leaders encouraged other Athabascan villages to start their own buffalo herds.

A Holistic Approach at InterTribal Buffalo Council

Lisa Colome, Technical Service Provider for the Intertribal Buffalo Council in Rapid City, served as rangeland specialist, but like others who work there, she takes a holistic approach.

A Cherokee elder who came from Oklahoma for training told her of their first herd.

“I can’t tell you what it meant to us,” he said. “I really believe with the return of the buffalo there’ll be an awakening of our people.”

Teaching young people about traditional relationships and spiritual connections to the buffalo is important to Colome. “This is what tribes are seeking.”

Teaching buffalo values to children are important to Indian tribes. Young people have a natural awe of buffalo, reports Lisa Colome, Technical Service Provider at ITBC headquarters in Rapid City, SD.

“Native kids have a natural connection to the buffalo,” she says, her dark eyes warming.

“They’re just naturally born with this awe. They are never disrespectful and show genuine caring.”

She enjoys bringing children to see the buffalo.

“Once I brought a group of sixth graders. They watched silently as the buffalo ran over the hill out of sight. I said, ‘Just wait, I think they’ll come back if we’re quiet.’

“We peeked over the hill. The buffalo circled back and came within 25 feet. The kids had never been that close before.”

It’s easy to see that Colome is excited about her work, whether her day focuses on herd and forage health, or cultural and spiritual ties. Not always do tribal herds bring financial benefits, she knows—often quite the opposite. But always she sees cultural value.

‘I love being a part of developing tactics, plans and solutions that ensure buffalo are here for generations to come,” she says.

“Return of the buffalo awakens the native spirit—it gives us hope of better lives.”

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog