Part 1: Hunting Calves with Buffalo Jones in the Desert, 1886

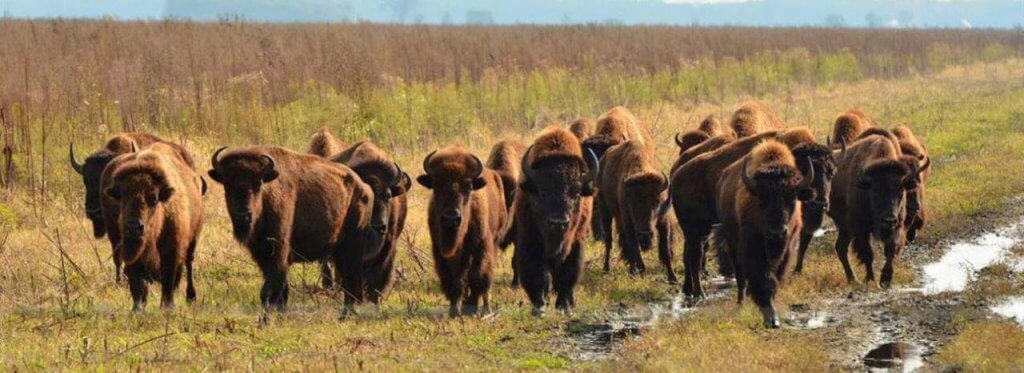

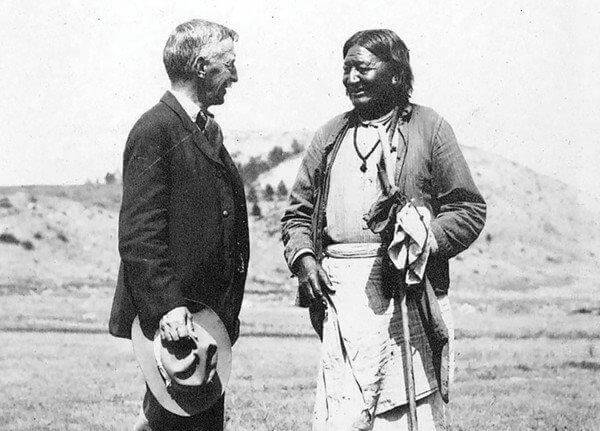

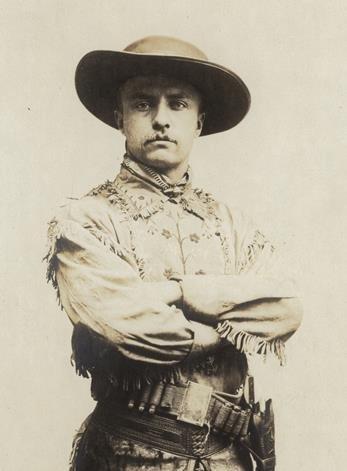

Into the desert sands. In 1886 a few wild buffalo could still be found in the most remote and formidable desert country of Texas. Buffalo Jones travelled into those desperately dry desert regions to capture calves. Credit National Park Service.

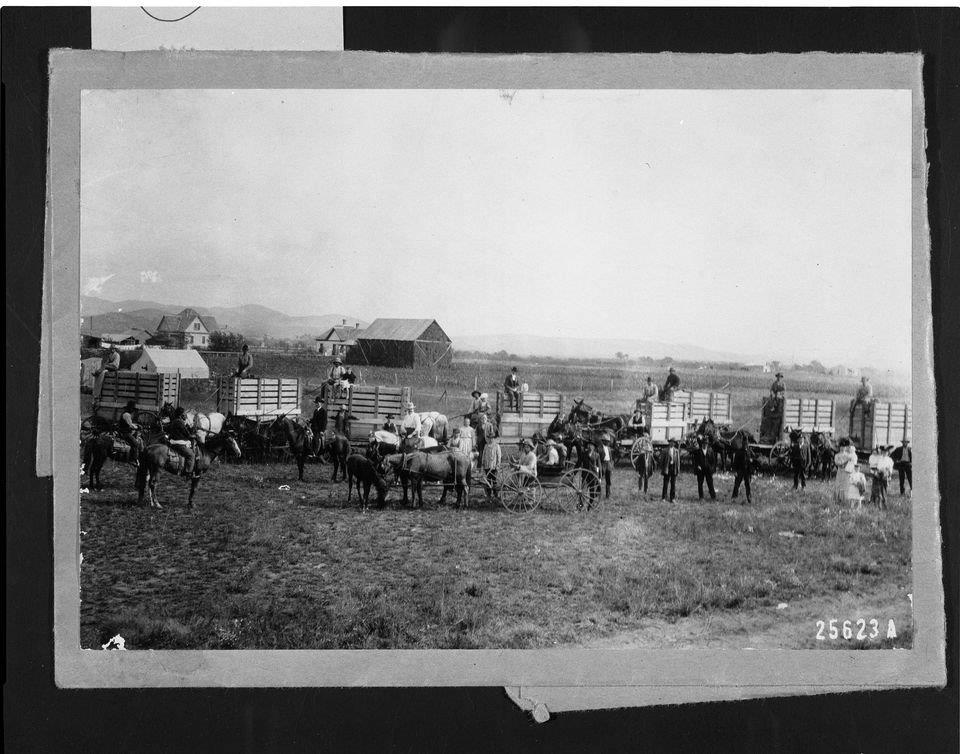

On a bleak cold day—April 24, 1886—Buffalo Jones struck out with Charley Rude and Newton Adams with a team of 3-year-old mules harnessed to a light spring wagon and another team hauling a heavier lumber wagon.

They took provisions for a 6-week expedition in Texas desert country determined to capture buffalo calves for Jones’ Kansas ranch.

Their point of departure was the little Kansas town of Kendall, on the Arkansas River not far from the west border of that state.

First challenge was crossing the treacherous Arkansas River—about a half mile wide, 5 feet deep with a quicksand bottom and choked with floating ice.

Jones met that challenge by commandeering two of his own “immense work teams”—large draft horses which happened to be working in an area quarry hauling out the “marble block” he was constructing at his home in nearby Garden City, Kansas.

The draft horses pulled the 2 rigs across the river and sent them on their way into the Oklahoma sandhills beyond and southwest across plains and deserts of the Indian Territory and the Panhandle of Texas.

It was to be “a long weary march—with the almost absolute certainty of not meeting a soul,” according to CJ Jones’ biographer, Colonel Henry Inman, who compiled his book, Buffalo Jones’ 40 Years of Adventure, by Charles Jesse Jones, from his journals in 1899.

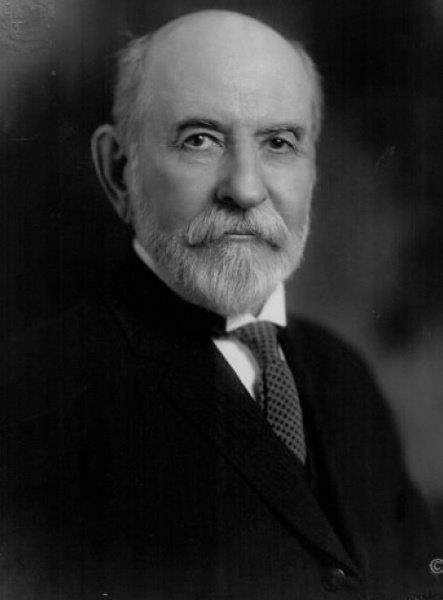

Buffalo Jones was already well known in Kansas as a legislator and successful town builder who came West as a buffalo hunter and worked as a mail carrier, station agent and rancher.

Although successful on many fronts, his current passion was to rescue buffalo calves and develop a herd of them from the wild.

Heading into No Man’s Land

Day after day the little party strained their eyes hoping to discover something that would relieve the monotony.

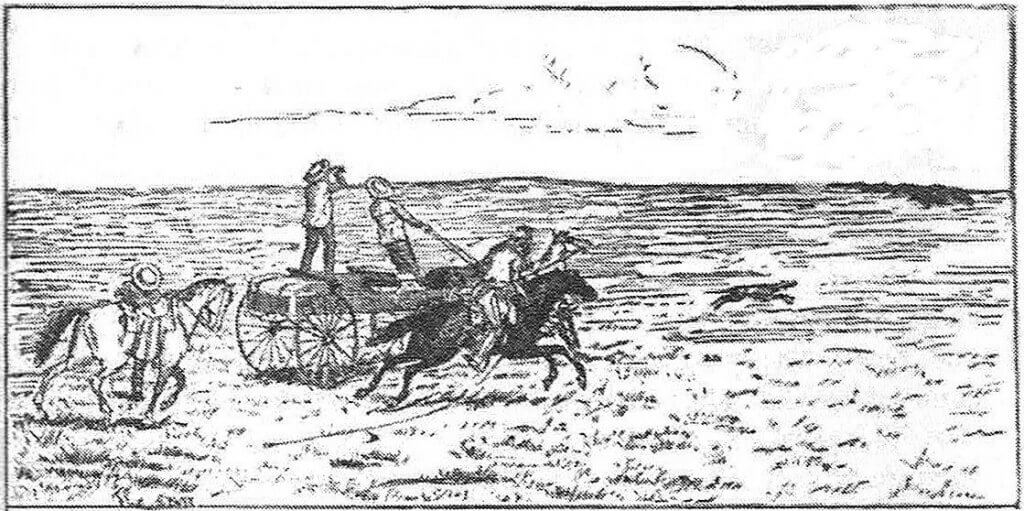

Scenes on the Journey. Jones’ party stopped at a last cattle ranch where ranching people kept quiet about the whereabouts of any wild buffalo herd. They left civilization behind and headed into ‘No Man’s Land.’ Credit JA Ricker, artist.

Always it seemed they were searching for water, as well as buffalo calves.

Then one day Buffalo Jones was driving his light team ahead, while Rude lay in the rear leading two saddle-horses which were reserved for the chase when the proper time would arrive.

Jones climbed a divide hoping to find water for camping, when he suddenly exclaimed.

“Great Heavens!. . . An elephant for sure!

Buffalo Jones sighted their first buffalo just before dark as he stood on the wagon seat at the edge of a high divide looking for water. Abruptly he sat down, swung the wagon down into a nearby ravine, handed the reins to Rude, then jumped out, crawled back to peek over the top, and shot a huge bull. Credit NPS, J Schmidt.

He gave the off horse a cut with the whip and whirled the team around so short and quick that it almost tumbled supplies out of the wagon.

Old hunter that he was, he had made it a rule to stand up on the seat in crossing a ridge, when after big game. Now this allowed him to see buffalo before they noticed his approach.

He sat down, drove quickly into the ravine, then jumped out, gave the reins to Rude and scrambled to the crest of the divide with his Winchester and peeked over.

In a few minutes, Bang! came the gun’s report. He turned and waved for Rude to come.

Three hundred yards beyond was a huge buffalo bull—dead! Killed instantly by his rifle.

Charley Rude and Newton Adams were excited and delighted to see their first buffalo.

They carved off about a hundred pounds of excellent meat and skinned the remarkably large head for mounting.

It was getting dark and the men had no water all day and were extremely thirsty. Worse, they had found no water in their last 20 miles. The horses were jaded.

Colonel Jones built a fire of buffalo chips on the highest point of the divide, telling Adams to keep up the signal so they wouldn’t get lost.

Then he and Rude mounted the saddle-horses and went in search of water. Jones took the high plateau and Rude the bottom of the ravine—each with a pail on his arm.

Hours passed, but neither returned to camp.

Adams grew anxious, frightened that Indians had captured both men. So he let the signal fire die out—and crawled off to hide in the long grass.

Near midnight he heard the sound of a gun far out on the prairie. He grew frantic with fear, convinced that Jones was killed—as the shot had come from that direction.

Soon he heard another report—from due north, followed immediately by two more to the east.

In terror he listened, sure that his time had come, forgetting entirely that he was supposed to return any shots he heard.

Very soon, to his terror, he saw what he supposed was an Indian riding a pony, passing by the camp. He shrank back into his hiding spot hoping all would go on by without discovering him.

His imagination told him the entire prairie was alive with hostile Indians hunting him!

Suddenly, one of his horses whinnied loudly at the passing horse, and his heart sank.

But the next second a voice called out, “Hello Adams! Where are you?”

It was Colonel Jones. His life on the Plains taught him how to find camp. He had come close even without the beacon fire he had started on the hill before he left.

Embarrassed, Adams leaped to his feet to help renew their buffalo chip fire on top of the hill.

By its dull glare Rude was guided into camp. In his pail he carried water, having found a small pond—while Jones had found none, looking from the high points.

Luckily, Rude had enough water to quench the thirst of the men, wet the throats of the four mules and Jones’ horse—his own having satisfied himself at the pond.

Colonel Jones broiled a large piece of delicious buffalo meat on the coals, brewed coffee and fried ‘slapjacks—being dubbed as good a cook as he was a hunter.

Then, the men’s stomachs filled and comfortable, they spent a jolly time until well after midnight listening to Jones’ stories of his experiences in the Great Plains and mountains.

Next morning, while the others fixed breakfast, Jones took his field glasses, strolled off in search of water, and in a short time discovered—a half mile to the southwest a beautiful pool of the purest and clearest.

He returned by a very high point where he could not resist stopping to contemplate the magnificent scenes all around him.

“For the Colonel is a lover of Nature in her quieter moods, as well as in the midst of an exciting chase after her wildest and dangerous creations,” wrote his biographer. “The air was so pure that not a vapor streaked the dawn, so that he could see over a vast area.

“He who has never been alone on the Great Plains and looked across a magnificent stretch of prairie at the moment of sunrise, cannot comprehend the thrill of emotion which fills one’s soul as he gazes upon such a scene—a landscape bewildering in its vastness.

“Colonel Jones stood entranced as he drank in the variety and charming features of the panorama, which only ended in the deep blue of the horizon, while imagination took him beyond.

“Little groups of antelope were either grazing, or having completed their morning repast were ruminating in the sunny ravines.

“Bands of wild horses were gamboling on the green hillsides, while here and there a wolf or coyote that had not yet finished its nocturnal prowling, slowly moved toward its den of seclusion as the sun rose in fullness of beauty and splendor.

“The wind was blowing from the south and it would not do for the scent of the party to be wafted in the direction of the herd, for buffalo will more quickly stampede at the smell of objects approaching them than by actual sight of the disturbing element.” E Nottingham Caprock Bison Release. Credit Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.

“Far in the distance was a herd of perhaps 20 monstrous buffalo, unconscious of the fact that so near was an individual who had enlisted his best efforts in ‘rescuing the perishing’ from annihilation.

“How slowly they move! In single file toward their sequestered nooks. Where the grass is thick and tender.

“Now the Colonel became intensely interested in this group of shaggy monsters as the light glinted upon their huge bodies.

“What he desired was the young bison, to raise at his ranch and thus perpetuate the species. There might be a hundred there, but the fact could not be determined, except by going closer.

“The Colonel returned to camp. With the animals all watered, breakfast was hurriedly dispensed of and soon

“They arrived at the crest of a high divide, where to the northwest, far beyond in a wide valley, a herd of 20 buffaloes was discovered—the same first seen by the Colonel in the early morning—lying down for their midday rest.” JA Ricker.

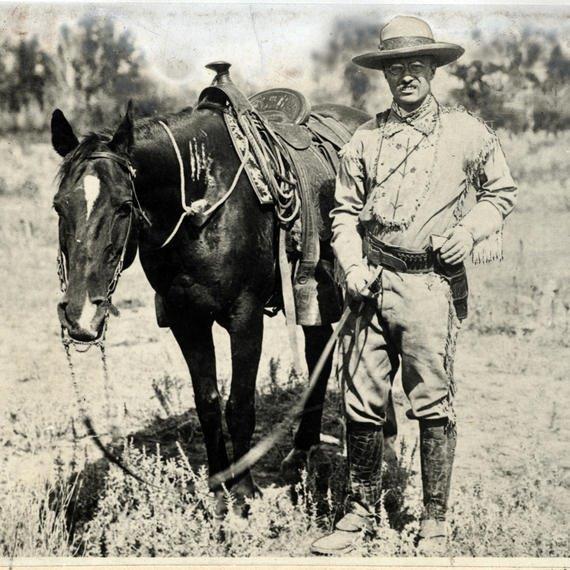

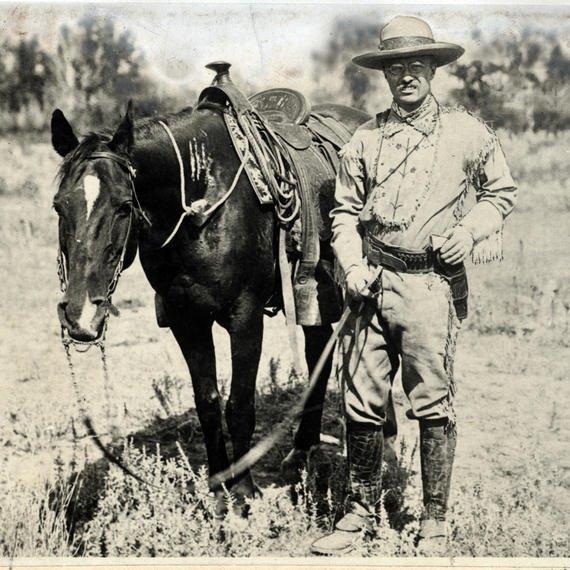

“The Colonel guided as usual, riding in the light wagon, leading his Kentucky thoroughbred, already saddled and bridled, with lasso carefully wound around the horn of the saddle and plenty of small rope to bind the calves if any were found in the herd.

“About 10 o’clock they arrived at the crest of a high divide, where to the northwest, far beyond in a wide valley, a herd of 20 buffaloes was discovered—the same first seen by the Colonel in the early morning—lying down for their midday rest.”

Here the team was immediately turned to the left, into a draw that opened into a larger one, situated between the buffalo and their pursuers—out of sight.

“Arriving at the larger ravine, a turn into it at the right was made, until another ravine from the west was encountered. Turning into it the most precautionary measures were adopted.

“The wind was blowing from the south and it would not do for the scent of the party to be wafted in the direction of the herd, for buffalo will more quickly stampede at the smell of objects approaching them than by actual sight of the disturbing element. And the odor of a white man is particularly obnoxious to them.

“The wind was blowing from the south and it would not do for the scent of the party to be wafted in the direction of the herd, for buffalo will more quickly stampede at the smell of objects approaching them than by actual sight of the disturbing element.” E Nottingham Caprock Bison Release.

They had to leave the wagons as the rattle of the wheels would certainly betray their presence.

At Last, Buffalo Calves

“Colonel Jones then cautiously took his saddle horse by the reins, drew up the cinch, and gave Rude orders to keep up and gather in the calves if any should be caught. And to lay on the lash and be sure not to lose sight of him.

“Then he led the horse as near as he dared, quickly mounted, laid flat upon the animal and galloped directly toward the buffalo.

“Every detail of his methods worked like a charm. If he had sat erect upon his horse the herd would have become frightened at once and been out of sight in a few moments. He did not deviate from a straight line in the slightest.

“To the buffalo, the object they saw was only a wild horse, looking at it as a very familiar sight. For buffalo are not able to distinguish a moving object from a stationary one, particularly if it is coming directly toward them,” according to Jones.

“Nearer and nearer the Colonel approached the herd, until he was within 200 yards, when they commenced to rise and move slowly away.

“In an instant confusion ran riot with the herd. Away they went, all going to the northeast as if they had been shot out of a cannon . . . To his infinite delight as the buffalo stood up, he saw four tawny calves among them, which had been hidden from view before, so completely were they masked by their mothers, nestled close to their great shaggy bodies.” NPS, Harlan Kredit photographer.

“To his infinite delight as the buffalo stood up, he saw four tawny calves among them, which had been hidden from his view before, so completely were they masked by their mothers, nestled close to their great shaggy bodies.

“In an instant confusion ran riot with the herd. Away they went, all going to the northeast as if they had been shot out of a cannon.

“By this time Mr. Rude had arrived with his mules at the top of the hill, from which commanding position he could grasp the whole exciting scene and take in every feature of the chase.”

“Colonel Jones was in excellent condition to do good work that morning. Getting so near the herd before it started and mounted on his best Kentucky runner was a combination of strategy and luck.

“Fearing that when he dismounted to tie a calf his horse might get frightened and leave him, he had fastened one end of the lasso around his animal’s neck, so he could be sure of keeping the horse from stampeding while binding the captive.

“As soon as the Colonel closed up to the surprised animals they ran all the faster.

“Mark how the cows protect their calves, sheltering them almost under their shaggy bodies!

“But old ‘Kentuck’ was in his prime and swept down upon the buffalo like a wolf on a wandering lamb.

“Now see the lasso whirling in mid-air from skillful hand. Away it goes into the midst of the fleeting shadows of the frightened animals.

“The horse comes to a sudden halt!

“A tawny calf is rearing and plunging at the end of the rope in its frantic struggles to escape the fatal snare!

“It is in vain. In an instant the Colonel is on the ground, grasps the little brute and in three distinct motions lashes its hind legs close up to its neck, slips the noose from its head and with a single bound that would have done credit to the most nimble circus rider, is firm in the saddle again.

“And see how the blooded horse sweeps over the prairie! At every jump the sod and dust are whirled 30 feet high in air, to land on the ground a hundred yards in his rear.

“What a wonderful picture! Scenes rivaling the chariot-racing in the Roman Coliseum of old!

“Every hope of success now depended upon the endurance of the thoroughbred. Like a hawk swooping down on its prey did the noble steed again close in on the flying herd.

“Now the lasso once more is whirled into the air. It shoots out like a cat’s paw and rakes in another calf!

“The Colonel was off as quickly as before, but as he was binding this second victim, he heard a loud grunt accompanied by a terrible rattling of hoofs immediately in his rear.

“Looking up to discover the cause of the strange commotion he saw the mother, who having heard her offspring bleating, was coming to its rescue—her eyes green as an angry tiger’s and hair all turned the wrong way.

“Looking up to discover the cause of the strange commotion he saw the mother, who having heard her offspring bleating, was coming to its rescue—her eyes green as an angry tiger’s and hair all turned the wrong way.” Jones threw his body into the saddle and Kentuck darted off like a flash with the enraged cow in close pursuit. NPS.

“With a bound that surprised the Colonel himself, he threw his body into the saddle and sunk both spurs into Kentuck’s flanks, upon which the horse darted off like a flash with the enraged cow in close pursuit.

“Kentuck whirled into the air like a small boy’s top—as the other end was still around the calf’s neck. There was no time to unfasten the rope from the horse’s neck, as the cow had already passed him and was fixing for another charge.

“All that could be done was to run Kentuck in a circle, using the calf as a pivot—or shoot the cow.

“Bang! Bang! Bang! came three reports from the Colonel’s 45 double-action revolver, but still the cow came nearer and nearer.

“The gallant hunter realized that there remained only two charges in the chambers, so he collected his nerve and waited till the furious animal was almost within reach of his horse. Then, leaning far back in the saddle, he took deliberate aim, firing the fourth time.

“The cow gave a furious snort and bounded away. She was hit high up in the shoulder, badly hurt but not mortally wounded. When she had gone about a hundred yards, she halted, shook her head and pawed the earth.

“Colonel Jones, taking advantage of this lull in hostilities, quickly slipped off Kentuck, tied one the of calf’s hind legs close to its neck, then drew the noose from its neck, again mounted and started after the fleeting herd a mile away, as though nothing had happened.

“Upon overtaking them, he profited by the lesson he had just learned and did not attempt to throw the lasso over another calf while the rope was attached to his horse’s neck. So, reaching down, he attempted to untie it, but the terrible strain it had been subjected to during his little fracas with the cow had so tightened the knot that he found he could not do so.

“The Colonel was well aware that if he stopped to untie it, it would be impossible to overtake the herd again, as his horse was fast becoming fatigued and not able to make another race.

“He concluded that if he pressed the herd hard enough the buffalo would get away and abandon the calves, which they would not do under ordinary circumstances.

“He then contented himself with an occasional dash between the calf and the remainder of the herd, causing it to bleat and beg for assistance.

“In every instance the cows and bulls invariably turned completely around, grunting in response, facing their enemy with a sold front of sharp-horned and vicious-looking heads, coming in the very impersonation of brute rage to the rescue of their little one.

“The Colonel then determined to resort to catching one of the calves with his hands, so he could hurriedly let it go if the herd pressed too closely.

“Reaching over to the right as they dashed over the prairie, he succeeded in grasping the tail of one of the calves (buffalo always run with their tails curved over their backs ‘like scorpions.’)

“The well-trained Kentuck knew that when his rider leaned to the right or to the left it was a signal to turn in that direction.

“So when the Colonel leaned to the right to grasp the tail of the calf, the horse promptly turned in that direction, unfortunately striking the calf with his feet.

“In an instant horse, rider and young buffalo were tumbled in a confused mass on the ground!

“The calf bellowed lustily, half scared to death, upon which 19 of the infuriated bulls and cows turned and started for the intrepid but reckless Colonel with all the intensity of concentrated wrath.

“Nineteen of the infuriated bulls and cows turned and started for the intrepid but reckless Colonel with all the intensity of concentrated wrath. . . Striking the horse a terrific cut with the rope brought him to his feet and senses in a second. Away he dashed with his master clinging to the saddle, out of the way of the impending clash of the charging buffalo.” Parks Canada.

“He at once realized the terrible predicament he was in, but his inevitable coolness in time of danger did not forsake him.

“Striking the horse a terrific cut with the rope brought him to his feet and senses in a second. Away he dashed with his master clinging to the saddle, out of the way of the impending clash of the charging buffalo.

“It was a ‘close call’—to employ a Western expression indictive of escape from almost certain death.

“But Fortune favored the hunter that day—as she has many times since—and the buffalo were doubly enraged upon arriving at the spot where the calf stood, to find their enemy vanished like a mirage.

“These two thrilling experiences, so closely following each other, did not abate one jot of the Colonel’s usual ‘nerve.’

“In a moment, it was ‘Up, Guards and at them! Again, as soon as he could straighten out matters, he dashed into the herd, running it until one calf, exhausted, was far in the rear.

“He pressed the buffalo at such a rate that they were soon so far away they could not hear it bleat.

“He then whirled his horse about, galloped back and met the calf, threw the lasso around his neck, dismounted, tied it and started for the other, the last calf.

“By careful tactics he succeeded in overtaking the herd and the last calf and its mother were separated from the herd, when with the last load in his revolver, he so wounded the cow that she was unable to keep up with her young one, and throwing the lasso over it, he captured the coveted prize.

“Three very exciting hours had just passed in the intense desperate struggle. Both the Colonel and his wonderful horse were so worn out that, after resting for a few moments they were so stiff that neither could make any rapid movement.

Mr. Rude was nowhere in sight and in fact was left 15 miles behind.

His horse exhausted, Jones took off the saddle, tied his horse to it, and set off on foot to find the wagon, his tongue already parched and swollen—with all their water in the wagon driven by Rude.

After two hours, near sunset, Jones saw a wagon far in the distance. Rude was heading for an antelope, which he later said he thought was a man on horseback. He was completely turned around and bewildered.

Together the two men gathered in the calves, found where Jones had left Kentuck, and made a ‘bee line’ for their camp—20 miles away, which turned out to be exactly where Jones said it was.

They arrived about 10 pm, and tied the calves 16 feet apart on a long rope.

But the men got little sleep that night as the calves were bawling constantly for their mothers.

Next morning they christened the calves: Lucky Knight whose mother had been in such a rage; May Queen which had thrown Kentuck; Robert Burns the first saved and Grace Greenwood, the last.

Sadly these last two did not survive the return trip back to Kansas.

Thirst and Opportunity in the Desert

Desiring to get more calves, Jones persuaded his party—now reluctant to go farther into the bleak desert—to continue farther southwest in Texas.

First, they took the buffalo calves they had captured back to one of the last ranches they had passed.

From then on, with misgivings—although courageous—Mr. Rude and Adams plowed on through deep sand and dry lands with scarce water for many miles and many days.

From the top of one of the highest points both men actually felt cold chills run through their nerves as they gazed upon the barren landscape stretching out before them.

To the very verge of the horizon there lay an apparently boundless desert of pure sand. Sometimes the whole surface resembled a high rolling sea with the spray flying high. The wind howled mournfully over the great waste.

Meanwhile Jones rode ahead searching with great confidence and optimism for water and buffalo.

He was more than a mile in advance of the wagons, plowing through the sand at a fearfully slow rate, when upon looking backward over his trail he saw the caravan had halted. Mr. Rude was signaling for him to return.

He swept the whole area with his powerful glass, saw there was no danger lurking from any quarter, so he signaled for them to come on—by riding in a circle.

The wagons did not move, but Rude mounted the other saddle horse and started for the spot where the Colonel waited, impatient for the loss of time.

Rude looked very pale when he arrived. He said that Mr. Adams refused to go any farther for fear they would all perish in the desert from want of water—and that he himself was not anxious to proceed. They had found no water that whole day.

Colonel Jones’ only answer was: “’Go where you like. I shall cross this desert! I know you never can find your way home—you would better choose the wiser part.”

He whirled his horse and rode straight away to the south, as he’d been going, without one parting look at his companions.

After some time he topped a high point out of sight and walked back to the crest of the divide, peeking over with his glasses to check on the wagon.

He saw that the two men had conferred fully 15 minutes. Then they climbed back in the wagon and began to follow his trail.

Mile after mile went by with no vegetation visible anywhere. Darkness set in early and Jones stopped to wait till the wagon came up. They made a dry camp that night.

Next morning, he set out early and about 10 am from a high vantage point spotted a big lake glistening in the sunlight, some 6 miles away. Or was it another mirage?

A band of wild horses was approaching the real or imagined lake. Soon he would know.

Jones insisted that wild horses are the best sign of water because—unlike buffalo—they come to water every day between 10 and 3 pm.

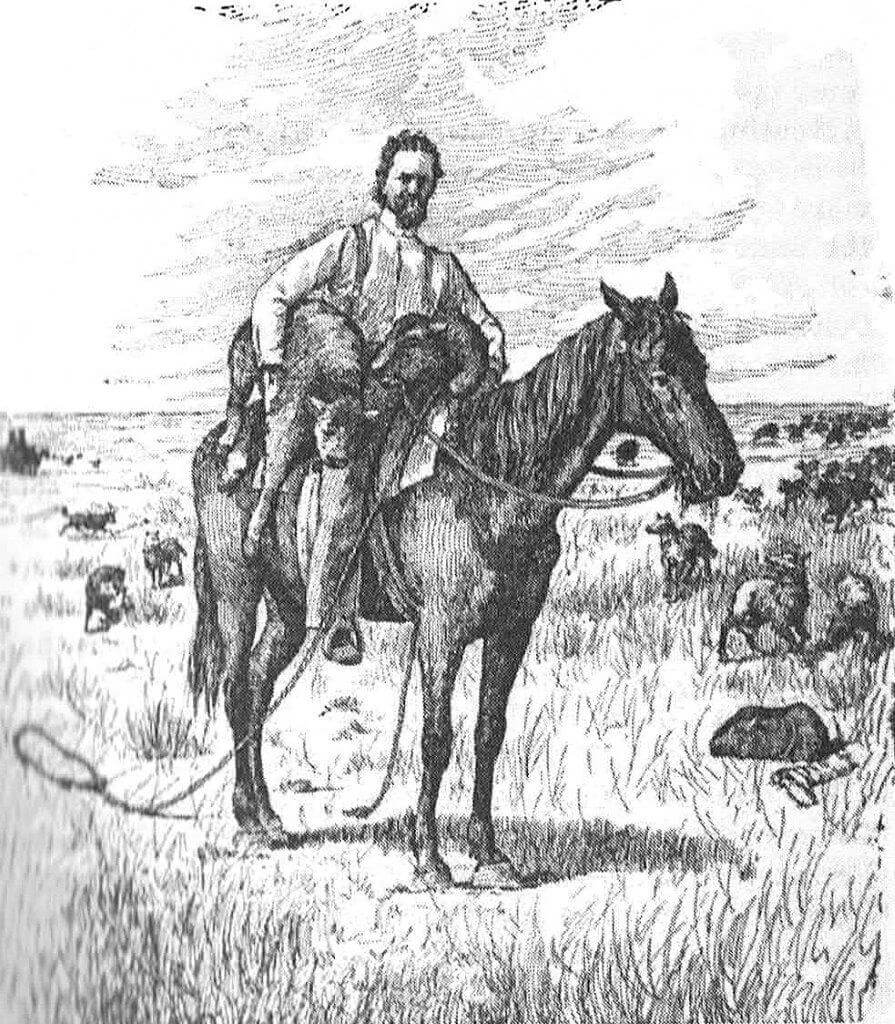

In the desert wild horses are the best sign of water because they come to water every day between 10 am and 3 pm, Colonel Jones told his men. In contrast, he said buffalo will travel three days or more before attempting to find water—so it is useless to follow buffalo hoping they are heading for water. Credit reddit.com.

In contrast, when they came up he told Rude and Adams, that a buffalo herd can travel three days or more without attempting to find a stream or lagoon of water.

The wild horses went to the spot at a gallop, lowered their heads and appeared to drink. Then they sloshed water a few minutes, turned about and went back the way they had come.

Water, without a doubt! Jones had watched wild horses in these maneuvers before.

The other two men were scarcely convinced the beautiful lake was real and not a mirage—until they actually dipped their fingers in the water.

That afternoon Jones saw through his glass a distant lone buffalo cow rapidly traveling south. He was certain she was frightened and hurrying to catch the main herd. She disappeared from sight, still going due south.

They followed with the wagon and covered at least 20 miles before stopping to camp. In all that long distance not an object was visible on the vast expanse before them.

Until just as the sun was setting. Then they saw 9 distinct large animals far off in the southwest, too far off to be sure.

And as Jones peeped cautiously over the next divide he saw what he believed was the last 600 wild buffalo in the world.

Next morning he left the wagon early with two horses to dash after the buffalo, telling his assistants to follow closely behind to pick up calves.

Unfortunately, in the light wagon they soon lost him in the distance and swirling dust of the rapidly stampeding buffalo herd.

The wolves and coyotes were very bold in this “No Man’s Land.” Dozens of them constantly prowled around his horses, slashing at the buffalo calves.

Jones roped 2 calves and wondered, “Shall I leave this one and take chances of the wolves devouring it?”

He decided, “Yes. Such an opportunity to catch calves will never again occur. I have travelled 500 miles for this all-important opportunity!”

Jones grabbed off his cowboy hat, tucked it under one calf’s neck rope. His coat went under another. His vest went under another.

By this time his horse was exhausted.

“Without checking their speed, Colonel Jones leaped on the second horse he was leading, cut him loose and rolled the steel spurs upon his faithful steed’s flanks.”

The 6th and 7th calf each got a cowboy boot tucked in against their neck rope.

Jones knew that wolves will not disturb anything that has on it the scent of man—thinking it is a trap. And at first they didn’t.

“But when the 8th was caught there was a desperate struggle,” according to the writer describing that first buffalo calf hunt.

“The horse by this time was all of a tremble, and covered with foam.

“The gallant Colonel, having no other garment he could well spare, mounted his horse, reached down and drew the baby buffalo up in his arms.

“He then started on the backward track. He could see a band of wolves encircling the 7th calf, so spurred up ‘Jubar’ to the rescue.

“He arrived at the spot just in time. The wolves had closed in on it and were ready to complete their tactics, when they were scattered right and left by the Colonel—who reached down and drew the supposed victim up in triumph.

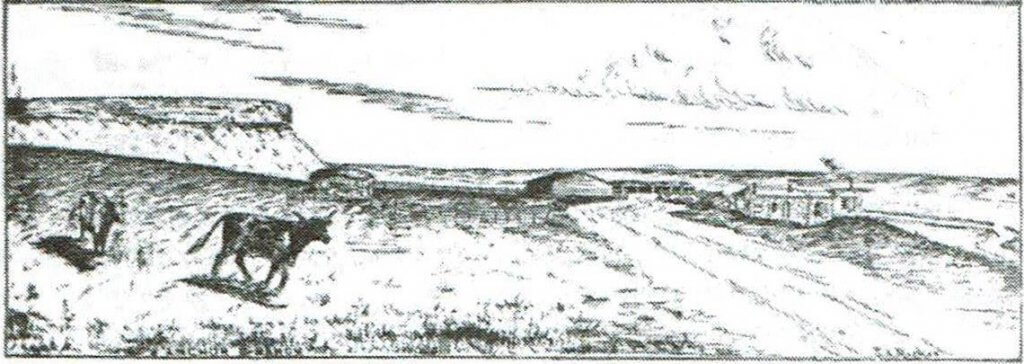

Jones carried two buffalo calves on the saddle while searching for the wagon—with more than 50 wolves and coyotes trotting all around as they accompanied him. Ricker’s sketch shows the buffalo herd in the distance at far right, while wolves surround the captured calves. Wolves came as close as they dared to the small trussed-up calf in the right foreground—being leary of the odor of one of Jones’ cowboy boots. Sketch by JA Ricker.

“This calf was also carried on toward his goal, with a band of more than 50 wolves and coyotes trotting all around as they accompanied him.”

“The next calf fortunately, had been left in a clump of grass which the wolves had missed entirely. When the Colonel reached it his courage failed.

“The danger was too great to attempt taking the 3rd animal up in his arms with the others.

“He let the calves down on the ground and made a dash at the wolves, shooting at them with his revolver, but they paid little attention to this kind of music.

“He was in a dilemma. In a precarious position. ‘Where in the world was the team?’

“He was worn out completely and his strength was gradually giving way. He longed to see the wagon.

“Certainly, his companions could not be lost. The trail of the herd was visible fully half a mile away.

“As often as he would venture off in search of the men, as often did the wolves return and attempt to get at the helpless calves. So he was compelled to remain and fight the vicious, hungry brutes.

“After more than a full hour’s worrying with the pack, he heard the report of a gun—but in an entirely opposite direction from where he expected.

“Upon this happy turn, he made a dash to the top of a high hill near by where he saw the wagon about a mile distant. The driver apparently was wandering at random over the prairie.

“By this time all the wolves were aggregating in one large pack around the three calves and he had to rush down on them in a mighty hurry to save his prizes.

“Yet they hardly noticed him, continuing to jump upon the little buffalo.

“He stood guard over them, preventing the wolves from effecting their purpose, only by the greatest efforts until the team came up.

“And to make matters worse—bringing with them another pack of the hungry devils, which had been escorting the wagon for miles.

“The report of the gun that had attracted the Colonel’s attention was caused by Mr. Rude, who had fired at one of the impudent monsters—a great gray beast, which fortunately he succeeded in killing.

“The men had gathered up three of the calves as they came to them. The three guarded by Colonel Jones were quickly loaded and the wagon going at as rapid a rate as possible back over the trail of the herd until the other two calves and the horse that had been cut loose were safely taken also.

‘The Greatest Herd of Buffalo in the World’

“It was found that the wolves had made no attack upon them. The foresight of the Colonel in putting his clothes around them had prevented it.

“When the last little buffalo was placed in the wagon, Colonel Jones sank on the ground, perfectly exhausted.

“Fortunately, there was a quart bottle of whisky in the light spring rig, it having been brought from home as an antidote to the possible bite of a rattlesnake, the country being full of them.

“A drink of this was administered to him by Mr. Rude and it immediately revived him.

“The team was driven to where chips could be procured.

“A dinner was elegantly served, consisting of deliciously broiled buffalo steak, hot biscuits and excellent coffee—the first warm meal the tired hunters had partaken of for 48 hours.

“An extraordinary appetite gave a zest to it, such as cannot be appreciated by those who have never experienced a plainsman’s capacity under similar circumstances.

“The party bade farewell to the ‘Staked Plains’ and drove to the ranch where they had left the five calves already caught.

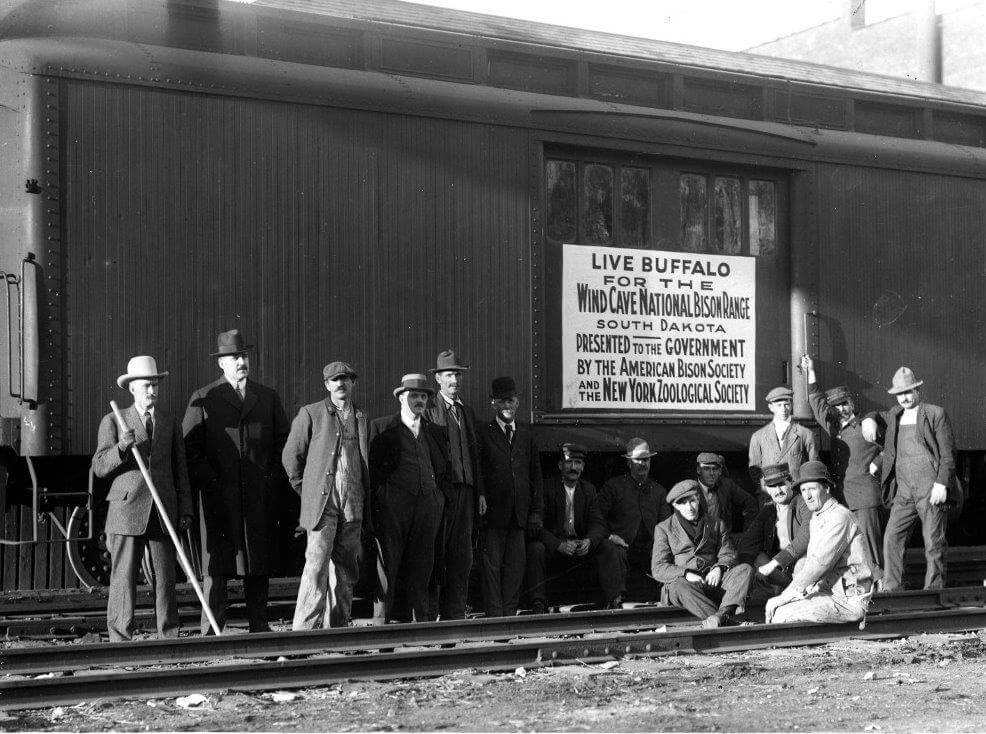

“Fourteen calves were secured—a whole wagon box full.

Buffalo Jones declared his expedition a great success, his first great effort at capturing the nucleus of what he believed would become “the greatest herd of buffalo in the world.” NPS.

They then took a ‘bee line’ for the Colonel’s home in Kansas and arrived there with 10 of the last buffalo calves in good health.

Four died on the way, due to fatigue and inadequate nutrition.

Buffalo Jones declared his expedition a great success, his first great effort at capturing the nucleus of what he believed would become “the greatest herd of buffalo in the world.”

Source: “Buffalo Jones’ 40 Years of Adventure,” by Charles Jesse Jones. Compiled from his journals by Col Henry Inman, 1899. Copyright 1899, by Crane & Co, Topeka, Kansas

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog