Many buffalo stampedes were described by hunters, soldiers and early settlers on the plains and prairies. They regarded stampedes as spectacular and grand, but “awful in its results,” according to David A. Dary in The Buffalo Book.

It took little provocation at times to get a stampede started—the yipping of a prairie dog, the cry of a wolf or coyote, a flash of lightening, or a clap of thunder could set it off.

Sometimes it took only one buffalo snorting and starting to run on its own, for others to join him in a chain reaction. In seconds a peaceful herd of grazing buffalo could become a charging mass that ran hard for ten or twenty miles.

Once running, the buffalo herd trampled everything in their path, including other buffalo too slow to keep ahead of the mass. They could not be turned. Or they would turn abruptly at some obstruction.

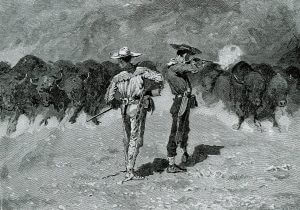

This drawing depicts Theodore Roosevelt’s account of a Texas hunt in 1877 by his brother Elliot and his cousin John, who were caught on the Staked Plains by a buffalo stampede. Their only chance was to split the herd, which they did by shooting continuously into the charging mass. Drawing by Frederic Remington.

In April 1846 George Andrew Gordon was out hunting with four friends on the plains of northwestern Texas.

Gordon became separated from the others and in trying to find them, he lost all but one of his rifle bullets. To see better, he began to ride his horse to the top of a nearby hill.

Suddenly he heard a low murmuring sound “as of the wind in the tops of pine trees.”

The sound increased, became a deafening roar. The ground shook and he said his horse shook with fear. But the only place of safety seemed to be a small grove of trees at the top of the hill.

A moment later he saw the buffalo coming and kicked his horse into a gallop.

The trees were about a foot in diameter and free of undergrowth. Only one tree had branches low enough for him to reach.

Gordon stood up in the saddle and grabbed a branch, pulling himself and his heavy rifle up into the tree.

The rushing buffalo were almost upon him, when they apparently heard or smelled his terrified horse, and tried to turn or stop, but slid and fell in a heap.

“In the twinkling of an eye,” he recalled later, “they were overwhelmed by the pressure behind. I have never seen two railroad trains come together, but one who has seen the cars piled up after a wreck can imagine how the buffalo were heaped up in an immense pile by the pressure from behind.”

The buffalo in the rear kept coming at a gallop, but as they reached the heap of trampled and dying buffalo just in front of the horse and man, they dodged to one side or the other.

He watched from his perch on the tree, while his horse stood there against the tree shaking with fear.

“I could now enjoy a spectacle which I fancied neither white man nor Indian had ever before seen. The front rank as they passed was as straight as a regiment of soldiers on dress parade. The regularity of their movements was admirable.

“It appeared as though they had been trained to keep step. If one had slackened in the least his speed, he would have been run over.”

It took nearly an hour of “alternate terror and pleasure,” as Gordon described it, for the entire herd to pass out of the small grove of trees, as he clung tightly to his branch.

He sat there a few minutes after they’d gone, wondering if he’d had a bad dream. Then he climbed down from the tree and took up the reins of his horse, which was still standing there shaking.

(David A. Dary, The Buffalo Book: The Full Saga of the American Animal, 1974. Swallow Press.)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog