Bears Arm, a second chief of the Hidatsa, told how he got caught on foot in the middle of a stampeding buffalo herd.

It was during the glorious days of “running buffalo.” Those days arrived with horses on the northern plains, sometime after 1700 and ended with the last of the wild buffalo in 1883.

The first horses arrived in Puerto Rico, North America, with Columbus and the Conquistadors on his second voyage in 1493.

The conquerors from Europe did not want the Natives to learn to ride. They succeeded for awhile.

But during the next years, through escape, raids and trading, horses worked their way north.

By the early 1700s the Commanche and Apache owned sizeable horse herds.

As they traded with northern tribes, a new horse culture grew up across the west that extended from Texas far north into the northern plains and prairies of Canada.

American Indians on the Plains became excellent riders—perhaps the best horsemen the world has ever known. Many men owned large horse herds.

From childhood, Native boys and girls lived on horseback. They grew up with horses, raced each other on horses, and helped train horses.

On coldest nights, they helped their fathers bring a favorite horse into the tepee when blizzards raged.

Once the Native Americans had horses, hunting became far easier and more exciting.

A good horse could run as fast as the buffalo—although they could not run at top speed for 10 miles, as the buffalo could.

But Native hunters had their tricks to turn a running herd, such as by killing the leaders.

Still, hunting accidents often happened and they could be deadly.

A good buffalo horse was well trained.

He could single out the exact buffalo he knew his rider wanted, cut in close and stay there—while dodging the huge hairy head with its viciously slashing horns, responding instantly to the rider’s knee pressure or a shift in weight, and avoiding badger holes.

At the same time his master was leaning over—with the utmost freedom to use both arms and hands in firing one deadly arrow after the other from his bow into the buffalo’s fatal spot.

The Hidatsas lived along the Missouri River at a place called Fish Hook Village, named for a sharp turn in the river.

One day, from across the river, near what is now Washburn, North Dakota, the scouts signaled. A great buffalo herd was grazing not far off.

The hunters made plans to run them, and performed the traditional ceremonies. Then they set off across the river.

Bears Arms wanted a large buffalo hide, so he decided to kill the largest bull he could find.

Most of the other hunters wanted tender and tasty meat for their families. So they were looking for younger cows and young bulls.

“I was not hungry just them. I did not want to kill cows.” Said Bears Arms.

“Riding along, I saw a splendid big fellow.

“I rode along his side—on the right side. You should always kill buffalo bulls from that side. You can shoot arrows better.”

He picked out the fatal spot. Low behind the front leg to reach the heart or lungs.

“I made the hit I wanted. But the arrow did not reach his heart.

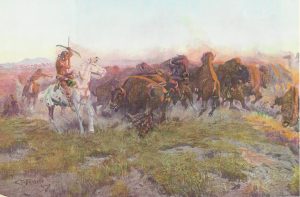

Riding deep into the buffalo herd could be extremely dangerous. Painting by CM Russell.

“The buffalo made a very quick turn.

“He caught my horse and threw him into the air.

Bears Arms leaped free of the injured horse.

“While he was tearing his guts out, I got away afoot.

Bears Arms was right in the middle of the running animals. He had to keep running or get run over.

He looked for help, but was separated from the other hunters. They shouted and tried to get through the stampeding herd, but could not come to his rescue.

No one could see well in the swirling dust and dirt.

“The buffalo were scared and running fast. The dust was thick. The roar of their feet was terrible.

“No one could reach me now.

“I grabbed a cow by the hair of her neck and ran along by her side.

“She was afraid of me.”

The cow kept trying to get away toward the outside of the main herd.

Protected by the bulk of her body against him, and still holding on to her long hair, Bears Arms worked his way clear of the stampeding hooves behind. He held his knife ready in case she turned on him.

“I got away then,” he said.

“I did not kill her because she had been good to me.”

The old bull stopped too, at the edge of the herd, stumbling and bleeding.

“He did not run far. He was shot in the lungs and was bleeding bad from his nose and his mouth now.

“He stood apart alone and died standing up.

“I lost my horse. But got the biggest hide there!”

It was a good day for the hunters, and Bears Arms began skinning his big bull.

(Story recorded by Colonel A.B Welch among oral histories given by older men of the Mandan, Arikara and Hidatsa along the Missouri River in Dakota Territory during the late 1800s.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog