Visiting Yellowstone Park in Winter-Part 1

Gardiner: Considered the original entrance to Yellowstone, Gardiner, Montana, at Mammoth is home to the historic Roosevelt Arch, which was dedicated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903. This entrance is open year around. Credit National Park Service.

As remarkable as Yellowstone National Park and Greater Yellowstone are during the rest of the year, in winter the park is a magical place.

Steam and boiling water erupt from natural cauldrons in the park’s ice-covered surface, snow-dusted bison exhale vaporous breaths as they lumber through drifts of white, foxes and coyotes paw and pounce in their search for prey in the deep snow, and gray wolves bay beneath the frozen moon.

Yellowstone in winter also is a place of vulnerability. Wildlife endure extremes of cold, wind and the absence of ready food. Their tracks through deep snow tell of tenacious struggles through the long winter. Park conditions in this most severe of seasons become critical to the mortality of wildlife and even to survival of park species.

No wonder the park is so popular in this magical, vulnerable season with those who have enjoyed its charms.

It is often said among park staff who live in Yellowstone that winter is their favorite season. Many park visitors who try a winter trip to Yellowstone come back for more.

Snowmobiles and other traffic pass bison traveling along side of West Entrance Road in Yellowstone Park. NPS Jim Peaco.

Oldest National Park in World turns 150

This winter, on March first, 2022, marks Yellowstone National Park’s 150th birthday. It’s the oldest national park on the planet and a World Heritage Site.

Signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant, America’s first national park was set aside on March 1, 1872, to preserve and protect the scenery, cultural heritage, wildlife, geologic and ecological systems and processes in their natural condition ‘for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations.’

Within Yellowstone’s 2.2 million acres, visitors have unparalleled opportunities to observe wildlife in an intact ecosystem, explore geothermal areas that contain about half the world’s active geysers, and view geologic wonders like the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

Yellowstone is as wondrous as it is complex. The park is at the heart of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, where nature and culture abound.

This might be a good year for you to experience Yellowstone Park again, beginning with a stunning winter visit—or even for the first time, if you’ve never been here.

Afterwards consider returning for the early spring Native American celebrations at Mammoth and to enjoy the lush flowers and wildlife of changing seasons—Spring, Summer and Fall in Yellowstone—Wow!.

As a native Montanan I’ve visited Yellowstone Park many times, the first time at age 6.

Well do I remember the terror of my first drive to the top of Beartooth Pass above Red Lodge—as a child of the plains. Sudden switchbacks plunged into deep canyons out the back-seat car window on a narrow road with drouping shoulders that fell away without railings into horrifying drop-offs.

I never thought we’d make it out alive, but when we finally reached the top we were delighted to jump out and throw snowballs with our whole family.

Many times through the ensuing years we hiked with forest rangers or sat on logs around a forest service campfire while they filled our ears with amazing stories and facts of wildlife, mountain adventures—and occasionally a tale of outrageous tourist behavior, and its fatal consequences.

Forest Service Rangers are always ready to answer tourist questions. About 4,000 employees work in Yellowstone Park each year. We hiked with knowledgeable Forest Rangers who told us amazing stories of wildlife, sat around their campfires on logs while they shared tales of adventure—and sometimes of reckless tourists with serious and even fatal consequences. JPeaco.

We always left the campfire with a dim flashlight it seemed and some great never-to-be-forgotten memories.

My sister Anne who lived in Helena with little children often took them to the geysers and geothermic lakes—but only with stern cautions for her own three little girls to stay on designated trails and out of the hot water.

At the same time she had plenty of anxiety for other children allowed to run freely up and down the boardwalks, pushing on each other, teasing and testing boiling thermal pools—and their parents’ patience.

Hank Heasler, the park’s principal geologist provides a warning, which he says is often ignored.

“Geothermal attractions are one of the most dangerous natural features in Yellowstone, but I don’t sense that awareness in either visitors or employees,” he says.

No, Anne didn’t sense awareness in those parents, either, as they casually hiked along, laughing and snapping photos of their children’s daring escapades.

The National Park Service publishes warnings, posts signs and maintains boardwalks where people can walk to get close to popular geyser fields.

Morning Glory pool—and a host of other hot springs—glow with colorful deposits of gold, green and blue. In Yellowstone’s geyser basins are 10,000 or more geysers, mudpots, steamvents and hot springs. Yellowsones’ geothermal areas contain about half the world’s active geysers—more than exist anywhere else in the world today. NPS.

Yet every year, rangers say they rescue one or two visitors, frequently small children, who fall from boardwalks or wander off designated paths and punch their feet through thin earthen crust into boiling water.

They remind us that Yellowstone protects 10,000 or so geysers, mudpots, steamvents, and hot springs. People who got too close have been suffering burns since the first explorations of the region.

Later from her winter home in Phillipsburg during the 1970s and 1980s Anne took her college-age girls skiing in Yellowstone Park for Christmas vacation when they were in the upper grades and college.

Alhough Old Faithful lodge might be open for Christmas, she said the rooms available at that time were scarce, but filled with beds for kids.

Cross-country skiing was on your own.

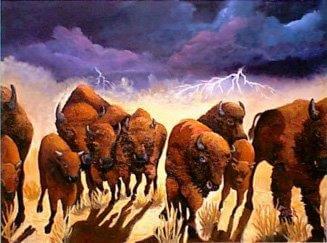

Often they’d ski right through big herds of buffalo feeding deep in the snow, sweeping their heads back and forth to uncover the grass. NPS.

They’d drive to a likely spot, snap on the skis and take off—ski to their hearts content—and return to the lodge before early winter darkness hit.

Often they’d ski right through big herds of buffalo wedged knee-deep in snow, sweeping their heads back and forth to clear the grass, which was still green under the snow.

The buffalo watched them with big eyes, but without moving as the young people skied past.

At the outskirts of the herd were always a coyote or two, ever watchful for a struggling buffalo or two that might not make it till spring.

Now, instead of two or three coyotes, are the newly reintroduced wolves hunting in family packs. Mostly they kill old or sick bison at the outskirts of the herd.

olves surround a lone buffalo in Pelican Valley. Reintroduced in Yellowstone in 1995, wolves have increased in numbers and hunt in significant family Packs. Herds of bison are well defended—armed with heavy slashing horns—but aging bulls who travel alone and newborn calves are often victims. NPS.

Yellowstone serves as the core of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, one of the largest nearly intact natural ecosystems remaining on the planet.

Yellowstone has the most active, diverse, and intact collections of combined geothermal features with over 10,000 hydrothermal sites and half the world’s active geysers.

The park is also rich in cultural and historical resources with 25 sites, landmarks and districts on the National Register of Historic Places.

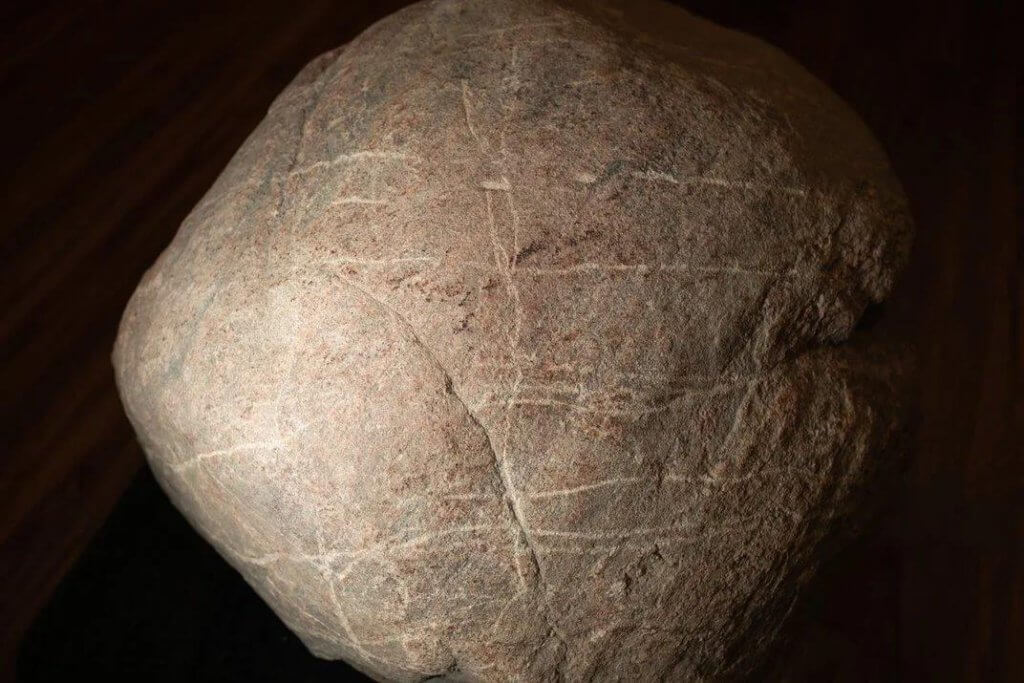

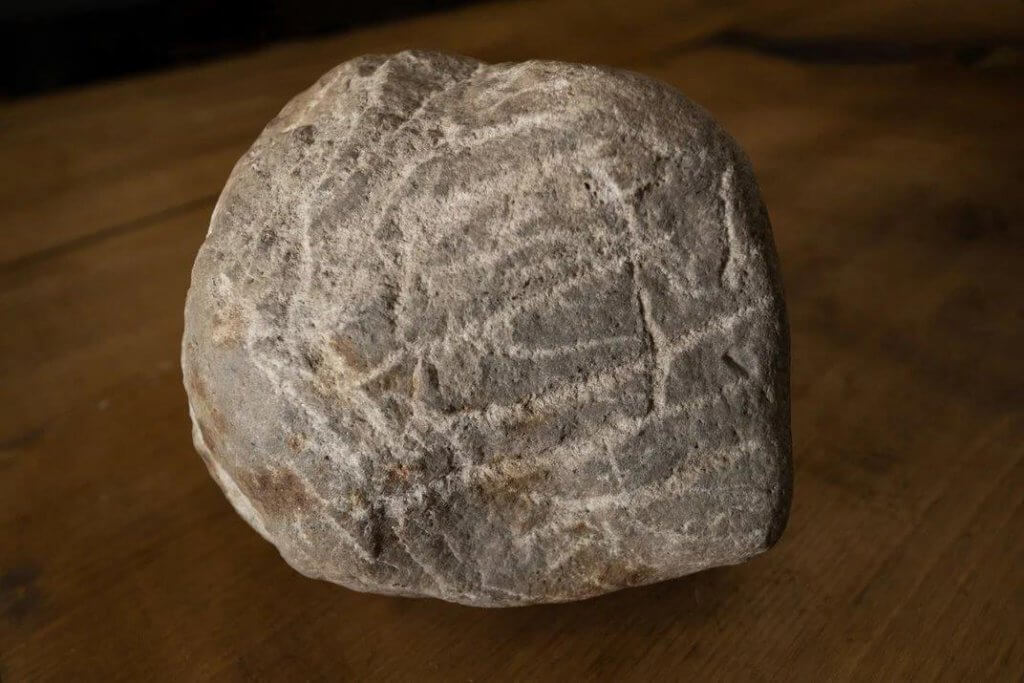

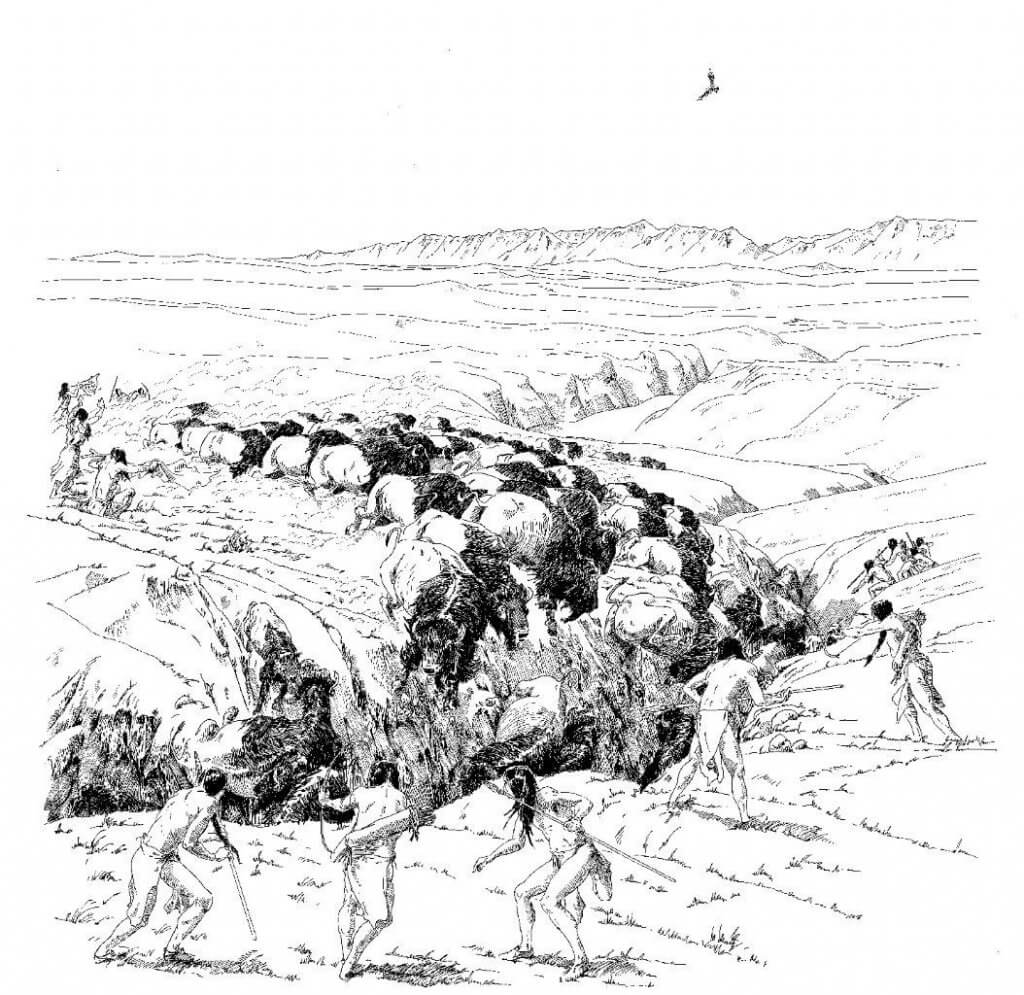

Many Native American Tribes have traditional connections to the land and its resources. Located as it is where the Great Plains, Great Basin and Columbia Plateau converge, the Park saw lots of traffic for over 10,000 years before Yellowstone became a national park.

It was a place where Native Americans came to hunt, fish, gather plants, quarry obsidian and use thermal waters for religious and medicinal purposes.

“Yellowstone’s 150th anniversary is an important moment in time for the world,” says Superintendent Cam Sholly.

“It’s an opportunity for us to reflect on the lessons of the past while focusing our efforts to strengthen Yellowstone and our many partnerships for the future.

“I applaud and share the vision of Secretary Haaland and Director Sams on our responsibility to more fully engage with Tribal Nations to honor and learn from their ancestral and modern connections to Yellowstone.”

Tribal history goes back 10,000 years or more in the Park. Tribes will join in celebrating Yellowstone Tribal Heritage Center project— including a tepee village near Mammoth.

The park has already conducted substantial outreach to Native American Tribes, inviting them to participate directly in this anniversary.

Multiple Tribal Nations will be present throughout the summer at Old Faithful as part of the Yellowstone Tribal Heritage Center project.

Tribes are also coordinating with Yellowstone staff to install a large teepee village in the park near the Roosevelt Arch at Mammoth in August. There tribal members will interact directly with visitors about their cultures and heritage.

Thus, Native American history in Yellowstone Park goes back 10,000 years or more.

Exploring ‘Colter’s Hell’

The history of white explorers in the park spans less than three centuries, but is quite dramatic.

The first white man to see and describe what is now Yellowstone National Park was J ohn Colter , in 1807.

Known as the original ‘Mountain Man’—American trapper and explorer—Colter went to the area alone to find fur trading partners for Manuel Lisa among the Native Americans.

He traveled over 500 miles to explore and establish trade with the Crow nation.

When he told people about the geysers, geothermal lakes and mud pots that bubbled, spurted and erupted into the air, no one believed him. They called it ‘Colter’s Hell.’

As the first white man in Yellowstone, John Colter probably saw scenes like these bison in Lower Geyser Basin in winter. People called it “Colter’s Hell,” and did not believe him. NPS photo credit Jacob Frank.

Colter began his mountain adventures traveling with the Meriweather Lewis and William Clark party to the Pacific Ocean. A young man from Virginia with skills in the deep woods, he proved to be a trusted hunter and route finder for the expedition from 1803 to 1806.

On their return trip they met two trappers heading up the Missouri River in search of beaver furs. Lewis and Clark released Colter to lead them back to the region they had just explored.

Over the course of that winter, he explored the region that later became Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks.

He arrived back in Lisa’s fort in March or April 1808. Not only had Colter traveled hundreds of miles, much of the time unguided, he did it in the coldest part of winter.

On one occasion he was captured by warring tribes, disarmed, stripped naked and forced to run for his life—pursued by a large group of young warriors.

A fast runner, after several miles the nude and freezing Colter was exhausted and bleeding from his nose but was far ahead of most of the warriors with only one still close behind.

He managed to overcome the lone man, took his blanket for warmth and continued running ahead of the rest until he reached the Madison River, where he hid inside a beaver dam. After dark he climbed out and walked for eleven days, 200 miles, to a trader’s fort on the Little Big Horn.

In 1810, after discovering that two of his partners had been killed by hostile tribes, Colter decided to leave the wilderness for good, and returned to St. Louis. He’d been away from civilization for almost six years.

Around that time he visited with William Clark and provided valuable information of his explorations since they had last met. From this, Clark created a map which, despite certain discrepancies, was the most comprehensive map produced of the region for the next 75 years.

Colter married, had a son and purchased a farm near Miller’s Landing, Missouri, now New Haven. During the War of 1812, he enlisted and fought with Nathan ‘s Rangers but died the next year.

Known as the original ‘Mountain Man’—American trapper and explorer—Colter was born in 1775 and died in 1813 while still a young man.

Colter is best remembered for the explorations he made during the winter of 1807–1808, when he became the first known person of European descent to enter the region which later became Yellowstone National Park and was first to see the Teton Mountain Range

A Bison Hazing We Will Go!

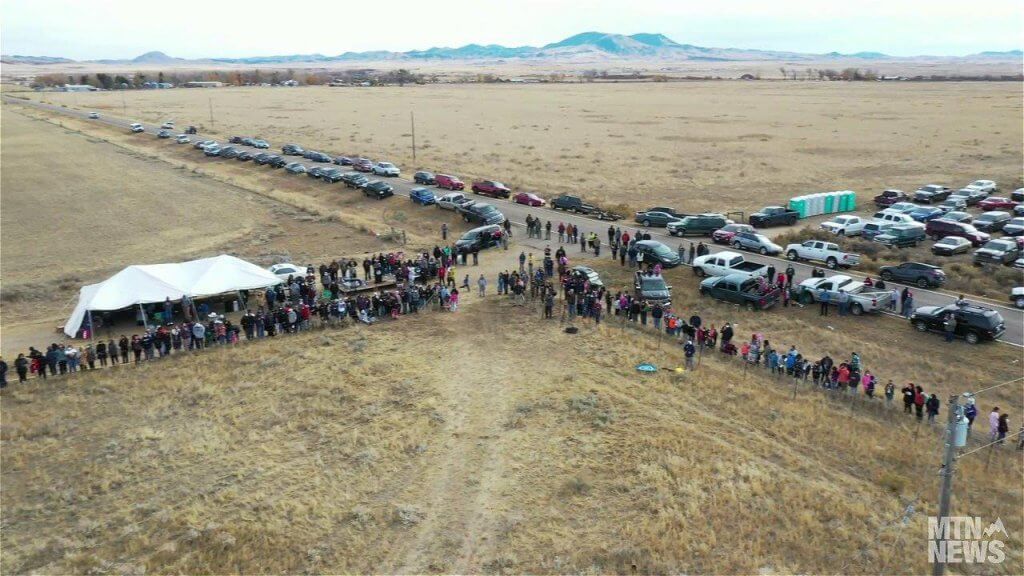

You may like taking part in bison hazing on horseback at the end of winter.

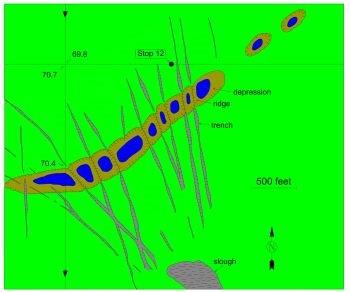

No, this isn’t your standard fraternity hazing, but in the wild is defined as simply herding or pushing an animal. Of course, it doesn’t physically harm the animal. It’s designed to keep roaming buffalo in their regional zones.

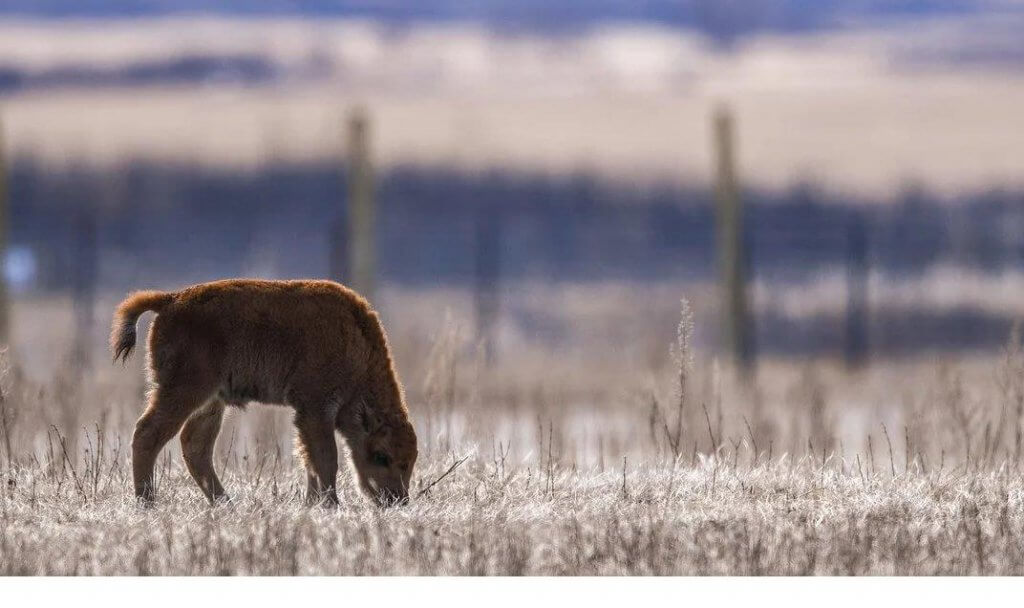

This annual hazing simply helps round up buffalo that have migrated outside of their native Yellowstone National Park habitats and return them to their traditional calving grounds before baby season arrives, which is typically every May or June.

This year has proved challenging, as the Montana Department of Livestock has reported a larger number of migrating bison within Zone 3, also known as the Western Management Area. This zone’s boundaries are defined as running along the South Fork of the Madison River, going around the western area of Horse Butte, heading north into Red Canyon and then returning south back into Yellowstone National Park. In fact, reports show that 40 buffalo migrated very close to Idaho’s border.

When the going gets tough and the horseback riders run into difficulty hazing the buffalo, a helicopter may be called in to help. It simply help aid human ability to further round up the returning head prior to their birthing season. Last year the deadline to have the bison returned to the park was May 15, just in time for the closed gates to reopen and welcome spring.

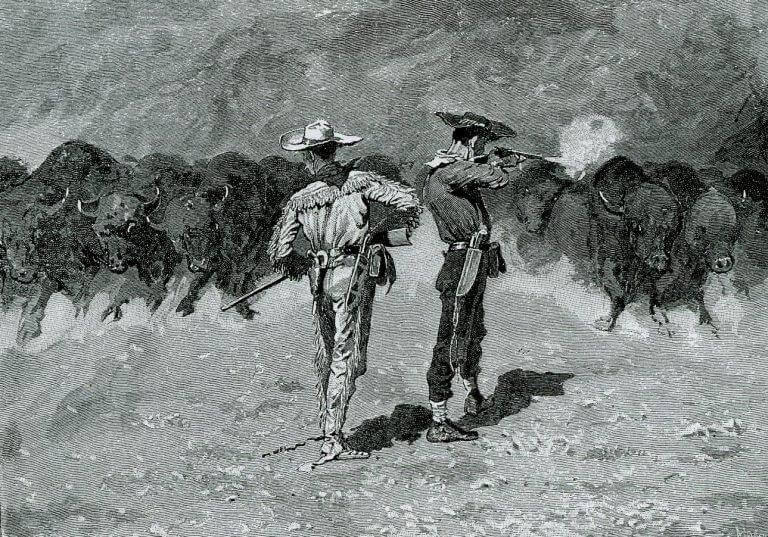

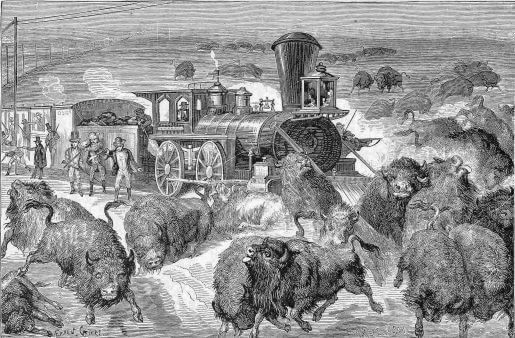

Bison are an interesting species. In fact, they are the largest terrestrial mammals in all of North America. Once dominating the grasslands of the U.S., estimates show that approximately 40 million bison once freely roamed our lands. However, by 1900, this number had dramatically plummeted, with just over 1,000 bison remaining.

Unfortunately, bison can only travel at a meager 30 miles per hour, which made them a hardy food source for Native Americans and white settlers.

While some bison were slaughtered for food, some were just killed for the ‘sport of it.’

Tragically, bison were killed in large numbers to simply make way for farmlands as people migrated west.

Fortunately for the remaining bison, environmental conservationists in the 1900s began breeding this species on protected lands, helping bring them back from the brink of extinction.

Adult bison live approximately 20 years in Yellowstone Park and begin giving birth when they are approximately three years of age, with males procreating at six years. (They often live much longer and calve every year on private ranches, without the large natural predators of the Park.)

Bison prefer savannas, open plains and grasslands and have a strictly herbivore diet. Constantly on the move, these massive animals are over six feet tall and weigh between 900 to 2,000 pounds.

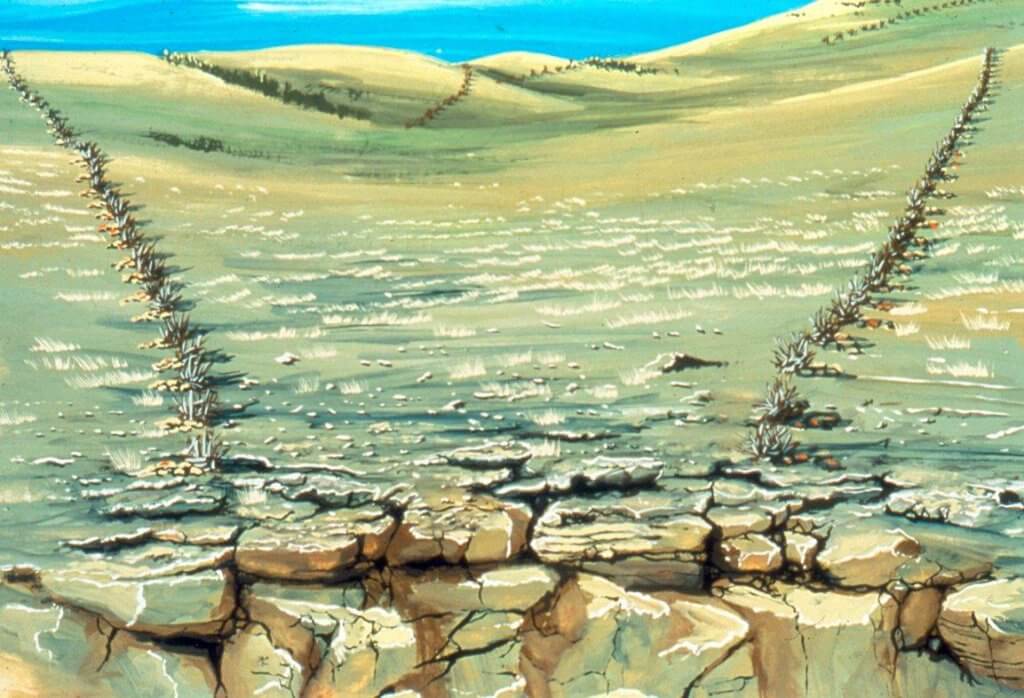

The winter months are hard on this species, especially during unusually cold winters where grasslands are lacking and snow gets crusted. Yet buffalo have evolved to survive in this country—and most of them do.

Find your Way in Winter Wonderland

Ever walked through a winter wonderland? Visit Yellowstone National Park between November and March and you’ll likely get your chance.

Covered in a blanket of white, the terrain looks as quiet and peaceful as it feels. Add in landscapes of steaming geysers for an ethereal feel and you’ve got a recipe for a great vacation!

Just be sure that you’re prepared. Here are some tips and dates from the Park Rangers to keep in mind.

Roads inside Yellowstone close to wheeled traffic on Nov. 8, 2021, except for the road between the North and Northeast entrances, which remain open year-round.

However, since the Beartooth Highway which leads to the East Entrance is also seasonally closed, the only way to enter the park in a vehicle during the winter season is through the North Entrance at Gardiner, Montana.

Beartooth Highway Outside of the Park at the East Entrance: Beartooth Highway (US 212, Red Lodge, Mont, to Cooke City, Mont. ) closes Oct. 12, 2021, and reopens in early May. Note: The summit of Beartooth—the only entrance from Red Lodge—is where you can throw snowballs beside the road in shirtsleeves in early June. Such fun!

A SnowCoach stops on highway for visitors to view Bison in winter at Gibbon Meadows, at a hot springs. NPS, Diane Renkin.

Road Openings to Over-Snow Travel: The park opens for winter recreation and over-snow travel in mid-December for the 2021-2022 winter. Roads will open to over-snow travel by snowmobile and snowcoach at 8 a.m. on December 15, 2021:

- West Entrance to Old Faithful

- Mammoth to Old Faithful

- Canyon to Norris

- Canyon to Yellowstone Lake

- Old Faithful to West Thumb

- South Entrance to Yellowstone Lake

- Yellowstone Lake to Lake Butte Overlook

- East Entrance to Lake Butte Overlook (Sylvan Pass)

Road Closings to Over-Snow Travel

The winter recreation season closes in March. Here are the spring 2022 closure dates. Roads will close to over-snow travel by snowmobile and snowcoach at 9 p.m. on the following dates:

- March 6, 2022: Mammoth Hot Springs to Norris

- March 8, 2022: Norris to Madison and Norris to Canyon Village

- March 13, 2022: Canyon Village to Fishing Bridge

- March 15, 2022: All remaining groomed roads

___________________________________________________________________________

NEXT: PART 2-Yellowstone Park in Winter

___________________________________________________________________________

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog