With a new white bison calf joining the herd in Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, community members say it’s a sign to get back to living in balance with nature.

The calf born on April 16 is the eighth white bison to be born on the First Nation in as many years. They are part of a herd of 104 bison in the community about 40 kilometres west of Brandon, Manitoba.

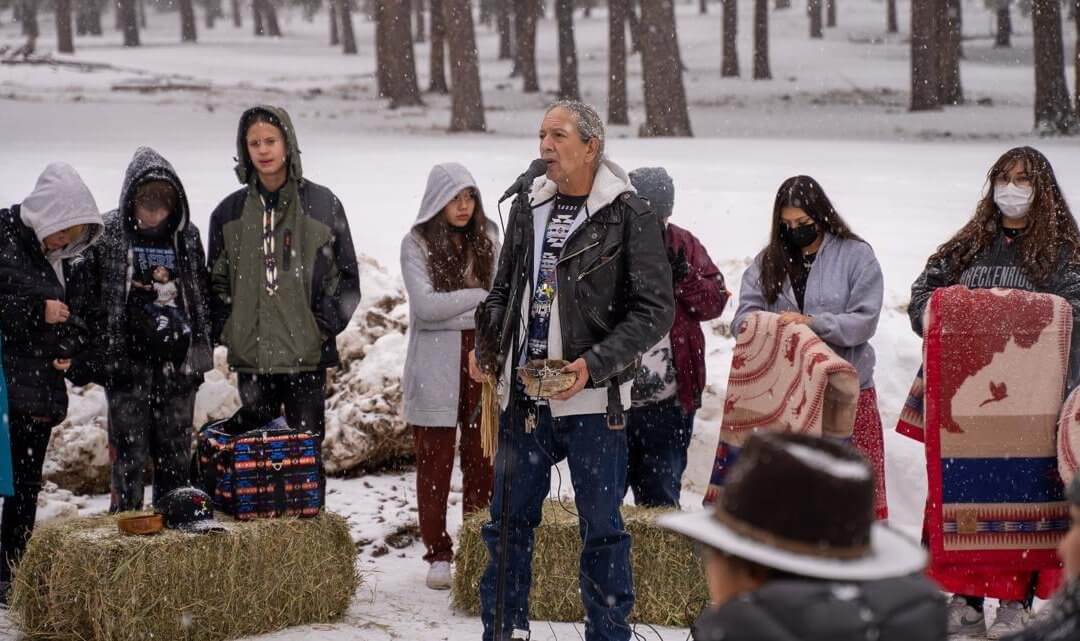

“The white buffalo is a blessing and a warning for our people, not just Native people but all people,” said Kevin Tacan, one of the community’s spiritual advisors, whose family also takes care of the herd.

Tacan said climate change is noticeable not only to us, but to animals as well

“They’re starting to come back, reminding us that we’re supposed to be living in balance with nature,” he said.

“We’re supposed to be living in balance with the animals and the natural world, and we’re not doing that.”

Tacan said First Nations have a special relationship with bison.

“We have a very close, spiritual relationship with the buffalo, because we both experienced genocide,” he said.

“And right now we’re getting our apologies from governments, but there are no apologies coming for the buffalo herd yet, and it’s something we’d like to see down the road.”

He said the bison are there for community members and other folks who come and pray.

“They pray for relatives who are sick or who are struggling in life with addictions or anything like that,” he said.

“They’re all different tribes that are coming here and doing their ceremonies here.”

Tobacco offerings tied in colourful fabrics line the fence, left by previous visitors.

“The buffalo would come and check them out, and listen to their prayers and then hopefully they’ll carry our prayers for the year, so that we can live a healthier, happier life,” said Tacan.

Keeping the herd wild

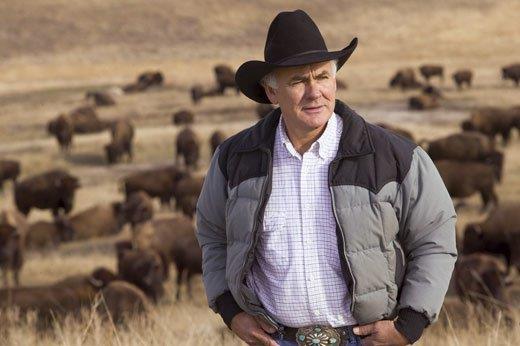

Tony Tacan, Kevin’s brother, is the community herd rancher, and a council member.

He said this is the second bison herd they started after being given a white bison by the Assiniboine Park Zoo in Winnipeg in 2010.

His family takes care of the bison, along with their horses.

“We took the responsibility on for the community, to ensure that they’re fed, watered, cared for,” said Tony Tacan.

“We’ve been doing that for so many years now.”

He said his brothers and cousins help out, along with his sons and nephews.

“We expect to keep them wild, we don’t want to domesticate them,” he said.

“That’s not the way of our people.”

Tony Tacan said there will be upcoming changes to the area, with a cement pad created for the elders’ handi-van, and signs on the main road directing people to the compound. A space for gatherings is also in the works.

“We make sure we have a place for people to come and pray; it offers people hope,” he said.

“Times being what they are, we need them to come here and feel better.”

(From The CBC)