Mexican Bullfight

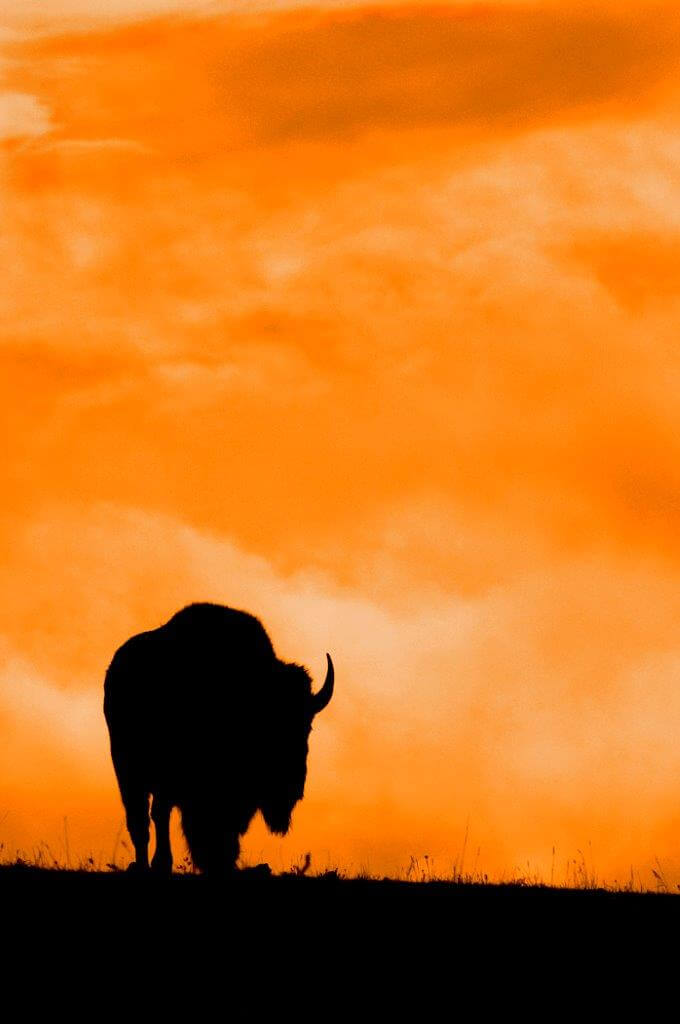

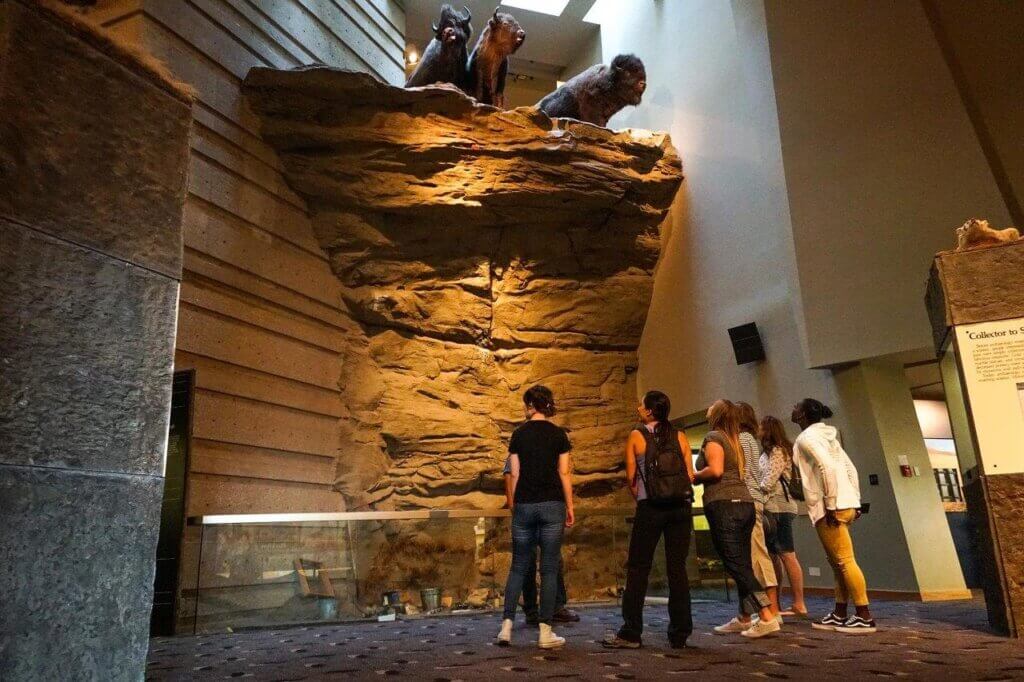

Scotty Philip grazed his Buffalo in rugged badlands on the west side of the Missouri River near Pierre. Photo Harlan Kredit, NPS.

One day a group of Mexican dignitaries from Juarez, visiting in Pierre, SD, came up the Missouri River on a tourist boat to have a look at Scotty Philip’s famous buffalo herd. With great interest and disdain, they eyed the shaggy beasts grazing up the draws and steep bluffs on the west side of the river.

As the tour boat came to a stop along the river’s west bank, they pointed out to each other the big buffalo bulls and mocked their apparent lethargic demeanor.

Contrasting these with their own flashy fighting bulls, they boasted to the tour guide and other passengers, with a trifle too much exuberance, that their feisty Mexican bulls would make short work of these lazy, slow-moving buffalo bulls.

In the frontier town of Fort Pierre, miffed locals took offense. Scotty Philip’s sporting friends made their own boasts and persuaded him to challenge the visitors to a contest.

One thing led to another and the two factions agreed to meet that winter in the Juarez bull-fighting ring. A bet was rumored at $10,000 for the winner.

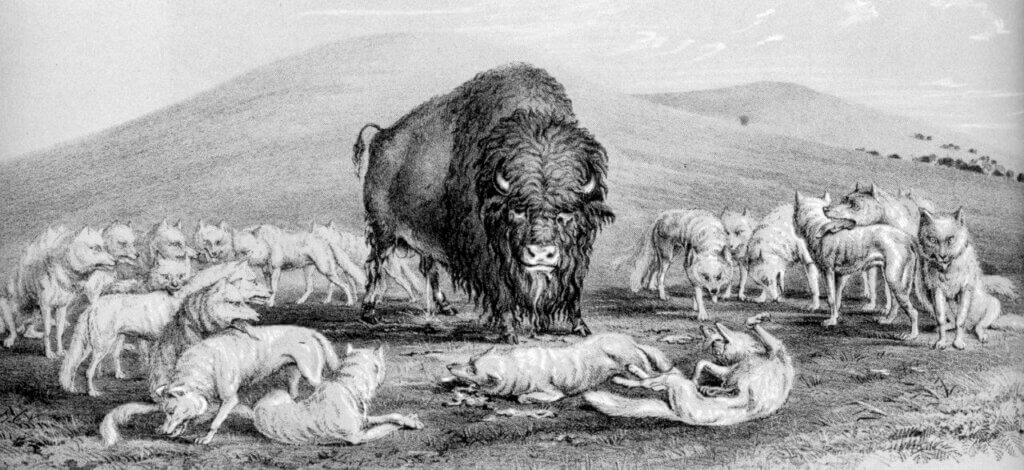

On a sidehill, Pierre and Pierre Junior appeared as lazy, slow-moving bulls. But in fact, they were alert and ready to defend the herd in an instant. Courtesy Vince Gunn.

Scotty Philip and his crew selected two bulls—a mature eight-year-old herd bull in his prime and an energetic four-year-old—and named them Pierre and Pierre Junior.

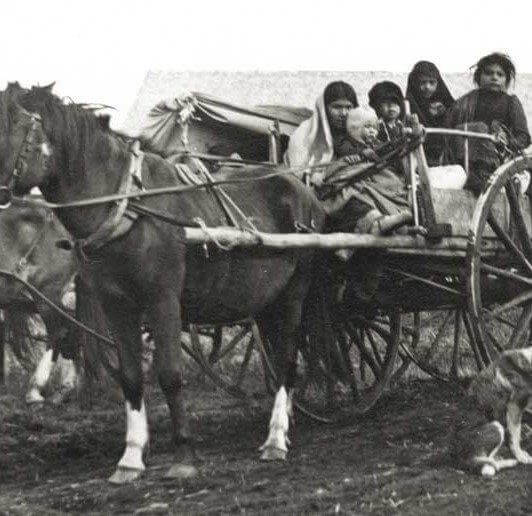

In early January 1907 the two bulls and three South Dakota men shipped out in a railroad car bound for El Paso and Juarez, just across the Mexican border. The rail car was fitted with heavy planking and penned off for each bull.

At the last minute, a severe January blizzard cut short Scotty Philip’s plans and he had to stay home with cattle emergencies. Instead, he recruited his nephew George, to represent his interests at the Mexican Bullfight in Mexico.

A lawyer just starting his law practice in Fort Pierre, George Philip had learned the cowboy life as a young Scottish immigrant on his uncle’s ranch. He travelled with two local experts, Bob Yokum, an enthusiastic promoter and friend, and Eb Jones, cowman and buffalo handler.

The first Sunday in January opened the Mexican bull-fighting season with a large and enthusiastic bull-fighting crowd in the stands.

The two buffalo bulls arrived just in time that Sunday morning. After 7 days of delays in shunting the boxcar from one railway line to another, they finally made it across the border and into an unloading chute.

The entertainment began that day with a parade of matadors, banderilleros and picadors dressed in red, blue and silver finery, dazzling with tinsel and sequins.

Next came four regular bullfights. By the time the fourth bull was stabbed to death in the arena, the crowd was shouting for the Buffalo to come out.

The main event featured what the Mexican audience fully expected to be a humiliation for the big, slow-moving buffalo. Pierre walked slowly into the ring, favoring his left hind leg, and stood quietly. Perhaps he was stunned by the hot southern sunshine in the middle of winter.

The crowd taunted him and jeered loudly.

Seated in the governor’s box as guests, Pierre’s three anxious South Dakota handlers murmured to each other their concerns. They worried that Pierre was exhausted from his 7 straight days cooped up in one end of a boxcar and was now suddenly prodded and pushed into the middle of a bull-fighting arena, in unfamiliar surroundings, filled with shouting people and strange smells.

The hot climate was an abrupt change from the extreme cold that his heavy winter hair coat had prepared him for.

On top of all this, he suffered a dislocated left fetlock, apparently from kicking the sides of the boxcar.

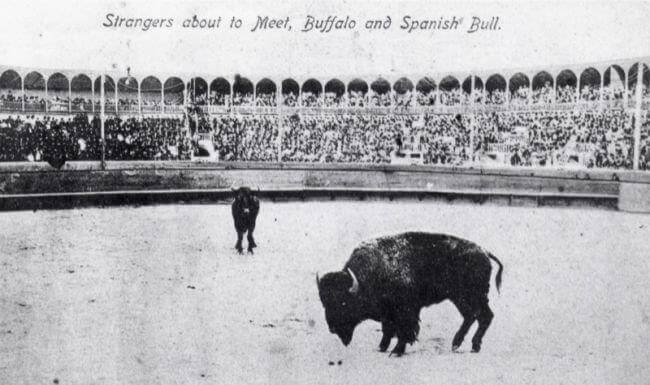

Scotty Philip’s buffalo and a Mexican bull in the Juarez, Mexico bullring, 1907. George Philip’s account mentions the buffalo’s injured “left hind leg,” but the photo suggests he may be favoring his right hind leg. Perhaps the photo is reversed, or the bull happened to raise his right hind leg off the ground as the photo was snapped, or George was mistaken, the author speculates. SD State Hist Society.

Cheering swelled from the stands as another gate opened.

Into the ring pranced a handsome red Mexican bull with sharp, treacherous horns, head up, two colorful darts flying from his withers. He stopped at a little distance and took the measure of his opponent, shaking his head fiercely and pawing the ground.

Pierre turned to confront him with massive head and shoulders, three-quartering his flank away.

Seeking an easier target, the Mexican bull circled. Suddenly he charged at full speed, intent on slashing Pierre’s flank with his long sharp horns, in what seemed certain to lead to a bloody goring.

Pierre stood still an instant and then in one smooth, rapid movement, pivoted his light hind quarters out of the way and met the bull head on, cracking heads. Photo Chris Hull, SDGFP.

The fighting bull staggered back and tried again—fighting bulls pivot on their powerful back legs, while buffalo do the opposite, keeping their massive head and shoulders out front, protecting their backsides

Pierre stood his ground as the Mexican bull charged to meet him. Again, they whacked heads

The Mexican bull backed off in confusion, evidently surprised at how powerfully Pierre’s huge, hard head smashed into the center of his smaller head, while escaping the twist of his own sharp, treacherous horns.

He maneuvered a better angle of attack. Again, he charged. Again, Pierre pivoted swiftly on his front legs, swinging his rear out of range.

Again, Pierre met the Mexican bull head on, this time with extra force that knocked the feisty fighter to his knees.

Not lacking in courage, the gutsy red bull charged a third time, against another powerful slash of Pierre’s huge head and horns, which knocked him flat.

Pierre simply stood his ground. He met every charge but didn’t follow up his advantage. After knocking the bull down, he ignored him, allowing him to rise and fight again.

The bull tried one last time and was again knocked flat, this time with an angry shake of Pierre’s head.

The courageous Mexican fighting bull had had enough. He circled the arena looking in vain for an escape gate.

The spectators roared their disappointment and disapproval.

The ring manager asked the South Dakotans if they’d be willing to let their buffalo fight another bull.

“The red bull is not feeling well today,” he said. “Another will surely put up a better fight.”

The three men agreed to allow it. They’d come a long way to see Pierre fight as they knew he could. A buffalo bull does not remain top herd bull without fighting continual fierce battles!

A second Mexican bull entered the ring with fire and fury. He eyed the strange shaggy beast quartering his flank away from him and charged—only to smash unexpectedly into that massive, well-armed head.

Three times Pierre knocked him flat. Twice he rose to attack again. The last time he ran for the gate and could not be persuaded to fight either buffalo or matador.

A third bull entered the ring, with the same results.

The three panicked fighting bulls now circled the ring looking for escape. Three bull fighters waved red capes and pricked their hides with silver swords, trying desperately to get them to fight. All the bulls refused.

Pierre regarded the smaller, cowering bulls with disinterest. He lay down, nonchalantly resting, chewing his cud, secure in the knowledge that—of course—he was the top bull.

At last, the crowd stood up and cheered him.

“Now I know this isn’t very sporting, but the bulls have disappointed me.” The ring master called to the visitors again. “I would like it if you’ll agree that I may turn in one more bull.”

“Turn in all the bulls you want, just make sure you give that buffalo room to turn around,” shouted one of the South Dakotans.

By the fourth fighting bull, Pierre was getting irritated. He rose to his feet and for the first time, pawed the dirt, warning the other bull away.

He charged. Crash! The Mexican bull flew backward and landed in a heap. He didn’t try again, and Pierre disdained following up on his victory.

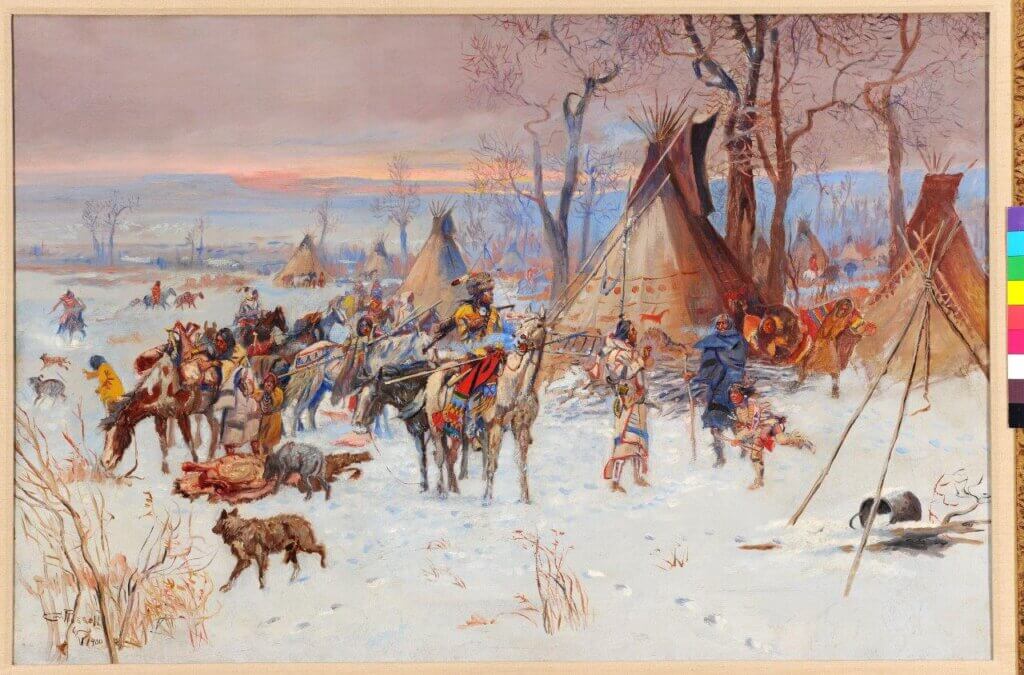

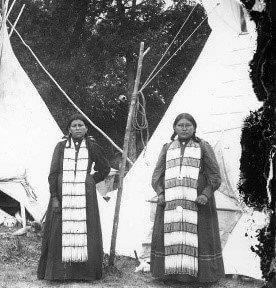

Lined up for a Matador photo in the arena are the three men in charge of the buffalo bulls—at upper left, back row, George Philip and Eb Jones (tallest) and Bob Yokum, at far right in front row. The others are also from Stanley County SD, West Pierre, and happened to be on hand in Juarez to watch the fight between Mexican Bulls and Buffalo. SD Historical Society.

The Mexican promoters called for a fight the next Sunday between Pierre Junior, the lively four-year-old buffalo, and a Matador with sword and cape in hand.

Pierre Junior

That day arrived with an exceptionally large and enthusiastic crowd on hand to watch the contest, advertised as four bull fights with matadors, followed by the buffalo and matador fight.

All were sorely disappointed.

The first bull let into the ring was the same handsome red bull of Pierre’s first fight from the Sunday before. Reputed to be one of the most splendid fighting bulls in the Juarez bull ring, the red bull shook his head, refused to fight the matador and ran for an escape opening.

Upon coming into the ring, the next three bulls repeated that same dismal performance.

Finally, an aggressive Pierre Junior charged into the ring looking for trouble. But the governor called off the match almost as it began, unwilling for their best fighters to suffer more humiliation.

He promised the crowd to refund their tickets.

As it turned out Scotty Philip was right. The Mexican fighting bulls—although gallant, fiery, highly-trained and said to be the finest in Mexico—were no match for a top buffalo herd bull.

Pierre Junior, his dignity intact, stood alone in the middle of the ring while the crowd cheered the magnificent stranger from South Dakota—mighty monarch of the plains and prairies

Epilogue: In another version of the “Mexican vs Buffalo Bulls” fight in Juarez, George Philip added that one of the men heard from a woman who saw these two Buffalo fights. She told him that several Sundays later, after Pierre’s leg had fully healed, he was advertised to fight again in Juarez.

Since they were not allowed to bring the bulls back into the U.S. after crossing into Mexico, the South Dakotans had sold them for $200 each to the ring master and a butcher.

Pierre’s promoters had built a pen of four-by-four timbers in the middle of the ring, the woman explained, with a chute leading into it.

Pierre ran down the chute, and a Mexican fighting bull followed.

The bull could not escape and Pierre fought with him and killed him.

A second and then a third fighting bull followed down the chute and Pierre killed them both. A fourth bull was run in and when the buffalo bull killed him he shoved the slain opponent through the side of the pen.

The woman said she heard that the buffalo bull then went on to fight in Chihuahua, Mexico City and Madrid.

George Philip ended his story with the question, “Maybe the lady had the story straight. Who knows?”

Source: George Philip, “Buffaloes versus Mexican Bulls.” Note that George Philip was one of the six cowboys delegated to round up and bring in the original Dupree buffalo herd 100 miles to their new home with the Scotty Philips, after Pete Dupree died. Fortunately for us and the buffalo’s loyal fans, many years later George described in detail the Mexican Bull Fight through a newspaper article, and then in SD Historical Review II, Jan 1937, and SD Historical Collections XX, 1940.

NEXT:

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog