Part 2—ITBC, 30 years—Yellowstone Bison Dilemma

From the time he learned of it, Robert “Robbie” Magnan director of the Fort Peck Fish and Wildlife Department in northeastern Montana was troubled by the annual buffalo slaughter of excess buffalo in Yellowstone Park.

It was not enough that the bison meat was distributed to Indian tribes in neat frozen packages.

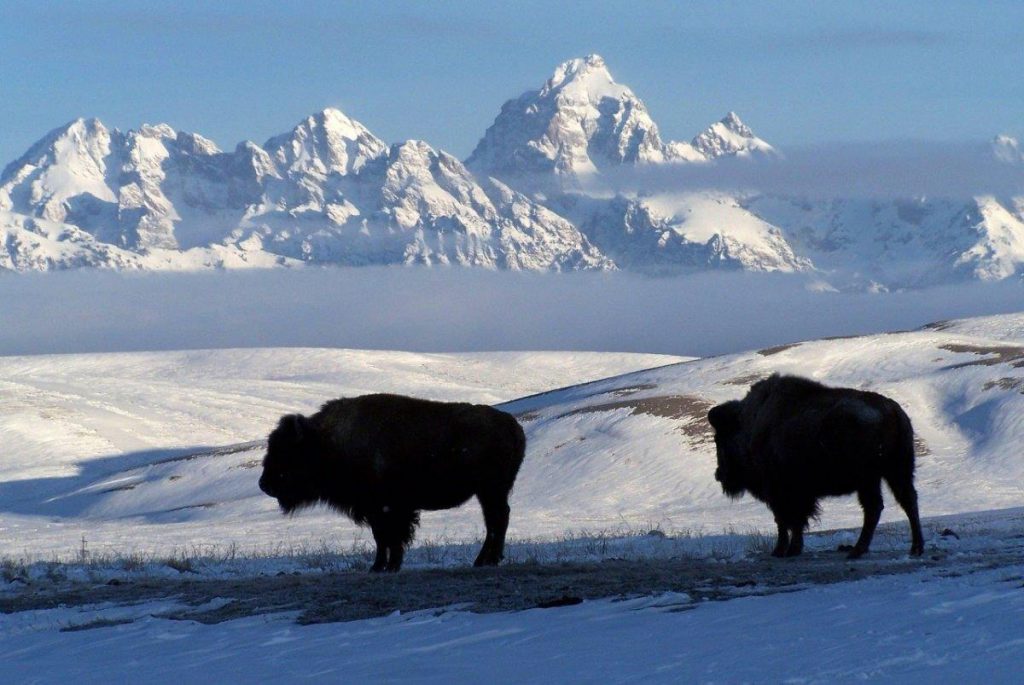

Magnan and other founding members of the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC) cherished the Yellowstone Park genetics that had flowed from free-roaming bison for more than a hundred years. They wanted those genetics in their own tribal herds.

Not quite the same as “always having lived wild” in Yellowstone Park. They knew that only a reported 23 buffalo survived poaching in the Park—back in the 1890s—and the wild Yellowstone pastures had been replenished by relatively tame buffalo from half a dozen sources, both US and Canadian. So not many were actually “pure.”

Still, the Yellowstone buffalo are special and many Native people deeply desire those genetics in their tribal buffalo herds.

The target population in Yellowstone Park is 3,000 buffalo, no more. But with new calves growing up in the herd it can quickly balloon up to 5,000 or more.

Because of the risks of spreading brucellosis to cattle herds, Montana law says that no bison can leave Yellowstone Park alive.

According to Montana Game and Fish, half the bison and elk in the Park test positive for brucellosis.

Hence, the surplus gets butchered, except for a few tribes allowed to come hunt at the borders in honor of ancient treaties that promised hunting rights.

One of the original founders of ITBC, Magnan has advocated to halt the slaughter of Yellowstone buffalo since 1992.

Two years later, in 1994, ITBC presented their first quarantine proposal to Yellowstone National Park, offering land and resources to support the development of quarantine facilities.

Over the years, Magnan often received bison meat for his tribe from this surplus.

Still, it rankled—even though the Park was 400 miles away, on a diagonal across Montana from his Sioux and Assiniboine Indian Reservation at Fort Peck.

Traveling the Big Pasture

But this was a gorgeous July morning in northeastern Montana. Problems created by winter overpopulation of Yellowstone Park buffalo seem far away.

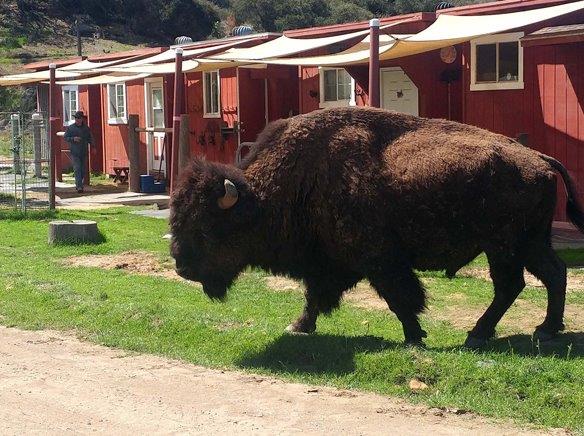

Sweet breezes waft across the flat between the higher bluffs and the badlands below as Robbie Magnan heads his pickup farther north into the large quarantine pasture.

I was privileged to ride along over the green hills that summer morning in 2014.

Below us to the south we could see bits of the silver ribbon that was the mighty Missouri River—flowing east as it does through most of Montana.

We were looking for the 39 buffalo from Yellowstone Park that recently came to live in this generous pasture—about 20 square miles (equal to a rugged chunk of land four miles by five)—13,000 acres.

They have lots of space to roam and might be anywhere—up on the grassy plateau or down one of many gravel and juniper draws.

Magnan says this herd of buffalo often walk 8 or 10 miles a day while grazing.

They keep moving, so he never knows where to find them.

“I promised I’d look at them every day and that’s what I do.”

He chuckles and you know there’s nothing he enjoys more than bouncing over the grassy flats, up and over the dam and out on a high point of land each morning to scan the badland draws below for the little Yellowstone Park herd.

It was one step in an ambitious experimental program, and Robbie Magnan is an important link in the quarantine process.

He checks levels in a new water tank and the new, higher and stronger quarantine fence being built within the quarantine pasture for later Yellowstone Park arrivals.

It’s a well-fortified 320-acre pasture within a pasture—for extra security.

As we bounced over the terrain—sometimes on a dirt road or trail, sometimes straight across the prairie, up and down—Robbie tells me the amazing story of this small priceless buffalo herd and the quarantine research that brought it here.

The scientific research, still ongoing, studies whether Yellowstone Park buffalo that test negative for brucellosis as calves can continue to live disease-free.

The goal is to grow this very special herd and then, if still disease free, establish them in a wider area, where they can live and multiply on tribal lands outside the Park.

Magnan is pleased with his new six-wire buffalo-tight wildlife exterior fences—a smooth wire on top and bottom for deer to jump over and antelope to crawl under, with four taut barbed wires in between.

“As long as they have grass like this, water and the minerals they need—and we test the soils for that— they’ll stay in,” he says.

If not, they’ll go looking for what’s missing.

“We call them wide-ranging, not free-ranging like in Yellowstone. It’s not realistic to think buffalo will ever be free-ranging without fencing. They will always be in a fence.”

This lovely summer morning Magnan drives over two hours searching for the Yellowstone herd.

“Just one more place to look!”

We bounce over the next hill, down a grassy draw—and sure enough, there they are.

Magnificent, extra-large, extra-dark beauties, 39 young adults.

All these animals are the same age, since they were placed in quarantine as calves in Yellowstone Park, lived there several years before coming to Ft. Peck. Annually they have tested negative for brucellosis.

Although these buffalo are not family, because they were selected for diverse genetics, they have formed a tight family group.

They now have 12 calves and bunch together as they graze.

Curious and friendly, several walk over to surround the pickup, to sniff at us and grunt their greetings for a few minutes. A magical interchange.

Looking for treats, I thought. But they didn’t get any and moved on.

Best of all, there’s a new baby calf, born this morning.

The older calves are turning dark, the crests of their heads nearly black between little nubs of black horns, as it’s already mid-summer.

But this newborn baby is pure red-gold. He shines bright as a shiny new penny in the morning sun.

Magnan has hopes of increasing this cultural herd enough to achieve a natural diversity with a self-sustaining genetic base.

He has worked with the Fort Peck Fish and Wildlife for 20 years, 17 of them with their tribal buffalo herds.

“From the beginning of time, the buffalo have taken care of Native Americans. Now they need our help,” he explains.

In the distance, in another pasture, we glimpse a hundred or so of the Ft. Peck tribes’ other buffalo herd filing down a long hill to water.

Magnan calls the Yellowstone Park buffalo our cultural herd and the others—over there—our business herd.

He waves toward the buffalo surrounding us. These buffalo know him well. They also know his pickup.

“To us these are extremely valuable, like registered cattle. They’ll never be sold. We’ll use them only for cultural purposes.”

As we watched the Yellowstone herd, they spread out a bit, grazing, while several calves take the opportunity to nurse.

Then, still grazing, the herd comes together in a small, compact band and moves on up the green draw around a rocky point out of sight.

“The money we generate from our business herd is to take care of our cultural herd. This is a way we could feed our people if the social programs were stopped.”

One problem that concerns Robbie Magnan: none of these buffalo grew up in a multi-generational herd—since they were separated from their mothers and quarantined together as calves.

He wonders: How will they learn the wisdom of the herd? How will they understand the complexities of normal buffalo relationships?

However, so far the quarantine is working. No brucellosis outbreaks with these maturing young buffalo.

And Magnan and his staff have shown themselves capable. None have escaped.

Then it came time to relocate an additional 145 buffalo.

These were held five years in quarantine on Ted Turner’s Green Ranch near Bozeman—and before that in Yellowstone Park quarantine at Stephens Creek in the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park—where they’d been captured and held in quarantine.

Montana authorities declared it too soon to divide them among the various entities, as planned. So instead they trucked them to Fort Peck’s quarantine pastures.

Robbie Mangan’s buffalo crew took over managing both Yellowstone herds.

“I enjoy them,” he says. “After 16 years they are still teaching me.”

The local press was on hand when the new herd arrived from Yellowstone Park at the Ft. Peck pasture. It was already dark.

As trucks rolled across the bridge leading to the release site near Poplar, a group of Assiniboine people stood waiting, singing a welcome.

An unforgettable moment for those on the bridge.

“We sang for them—a buffalo song,” said Larry Wetsit, vice president of community services at Fort Peck Community College.

“It’s a special day. Our people have been waiting and praying about this.”

During early reservation days hundreds of tribal members had starved, including his own ancestors, Wetsit said.

“It was all about having no buffalo. That was the low part in our history, the lowest we could go. This is a road to recovery.”

Larry Schweiger, president of the National Wildlife Federation, one of the agencies involved in the Interagency Bison Management Plan for dealing with Yellowstone Park brucellosis problems, was there for the release.

“We believe it’s the right thing to do for wildlife. It’s the right thing to do for the tribes. And ultimately the right thing to do for the landscape,” he said.

“What this means to me is the return of prosperity to our people,” said Wetsit.

An Assiniboine, Wetsit has been the medicine lodge keeper for over 20 years, a ceremony he learned as a young man.

“It’s a celebration of our life with the buffalo.

“What we’ve always been told, always prayed about, is that the buffalo represents prosperity. When times were good it was because our Creator gave us more buffalo.”

Iris Grey Bull, a Sioux member—the Fort Peck reservation is home to both Assiniboine and Sioux tribes—spoke about their close ties to the buffalo.

“The waters of our reservation form the shapes of buffalo,” she said. “One male is to the east and four females to the west.

‘Now they’re bringing back the buffalo. This is a historic moment for us. We’re rebuilding our lives. We’re healing from historical trauma.”

“I watched the bison come out of the trailers,” Schweiger recalled. “I was watching the faces of tribal elders and the women and children watching these big animals charge out of the trailers.

Homecoming on Tribal Lands

“I was so moved to see the reaction—a powerful thing to witness. After the animals were released the drummers sang a blessing. The snow was blowing,” said Schweiger.

“It was cold. It was dark. But there was a lot of warmth.”

On August 22, 2013, the remaining 34 buffalo of the same pure Yellowstone Park strain as those at Fort Peck were released on nearby Fort Belknap Reservation.

Montana’s governor Brian Schweitzer called the event a historic opportunity to bring genetically pure buffalo to this special place on the planet.

“These are the bison that will be breeding stock to re-populate the entire western United States, in every place that people desire to have them,” he said.

Gathered to welcome them with a pipe ceremony were 150 people.

“It’s a great day for Indians and Indian country,” announced Mark Azure, who heads the Fort Belknap tribe’s buffalo program.

The last two big bulls flipped up their tails and ran from the trailer to join the herd.

Mike Fox, Belknap’s tribal councilman, said the tribe’s goal is to manage the special buffalo herd and use it as seed stock for other places wanting to reintroduce the Yellowstone strain.

“It’s a homecoming for them,” Fox said. “They took care of us and now it’s time for us to take care of them.”

Robbie Magnan waited, his most prized herd was not allowed to travel to other tribes, as was planned.

Film: Return of the Native: 25 Year ITBC History

A wonderful film was made on the history of ITBC. I know our readers will enjoy it when you have time to check it out. Narrated by Mark Azure of the Fort Belknap tribe in Montana.

In this documentary you’ll learn more about the groundbreaking work that Tribal leaders have done to restore buffalo to Indian Country. It’s split into 3 parts—close to an hour long.

Also you may want to watch the related short video: ITBC’s “Returning the Buffalo.”

Just click on this website:

https://itbcbuffalonation.org/return-of-the-native-the-25-year-history-of-the-intertribal-buffalo-council/

Or you can watch the various parts of the film on YouTube: www.youtube.com/watch?v=AeZ4lrb4-hs

But on a rather sad note, the film ends with Robbie Magnan standing a lonely vigil by his empty quarantine pasture—320 acres. Enclosed by walls of 8-foot high woven-wire fences and inside that is a 2-wire electric fence strung within the perimeter.

Well barricaded against escape, but empty and silent.

After 2014 no buffalo came from Yellowstone to his quarantine pasture for years.

Progress was stalled while cattlemen protested the quarantine system in Montana courts. They remained concerned about losing their brucellosis-free status again—which would prevent them from selling their cattle.

Introducing the Indian Buffalo Management Act

Meanwhile new legislation called The Indian Buffalo Management Act was introduced in 2019 by Congressman Don Young (R-Alaska) to assure regular funding for the buffalo restorations programs in Indian country.

It was unanimously approved and passed out of the House Natural Resources Committee but did not make it to a vote in the 116th Congress.

According to his office, Congressman Young would likely need to reintroduce the bill in the 117th Congress. He pledged to continue working with tribal leaders, state and local partners, and other advocates to ensure that herds of these majestic creatures can be restored to their historical sizes.

“For hundreds of years, the American buffalo was central to the culture, spiritual wellbeing, and livelihoods of our nation’s Indigenous peoples,” said Congressman Young.

“The tragic decimation of these iconic animals remains one of the darkest chapters in America’s history, and we must be doing all that we can to reverse the damage done not only to the American buffalo, but to the way of life of Native peoples across our country.

“I am proud to be joined by Congresswoman Deb Haaland and Congressman Tom Cole, in addition to Alaska Native and American Indian organizations and countless tribes, as we introduce this critical legislation to protect a resource vital to Native cultural, spiritual, and subsistence traditions.

“I would like to thank the InterTribal Buffalo Council, in particular, for their advocacy and hard work on the development of this legislation. This bill is an important step to restoring once-vibrant buffalo herds, and I will keep working with friends on both sides of the aisle to see this legislation across the finish line.”

“The Pueblo of Taos greatly appreciates Congresswoman Deb Haaland’s support of reintroduction of Buffalo to Indian lands through her co-sponsorship of the Indian Buffalo Management Act,” said Pueblo of Taos leadership.

“This Act will allow the Pueblos of New Mexico to enhance existing herds, start new herds, reintroduce buffalo into Native population diets and generate critical tribal revenue through marketing.”

“When it becomes law, the Indian Buffalo Management Act will strengthen the federal-tribal partnership in growing buffalo herds across the country and in the process restore this majestic animal to a central place in the lives of Indian people,” said John L. Berrey, the Chairman of the Quapaw Nation of Oklahoma.

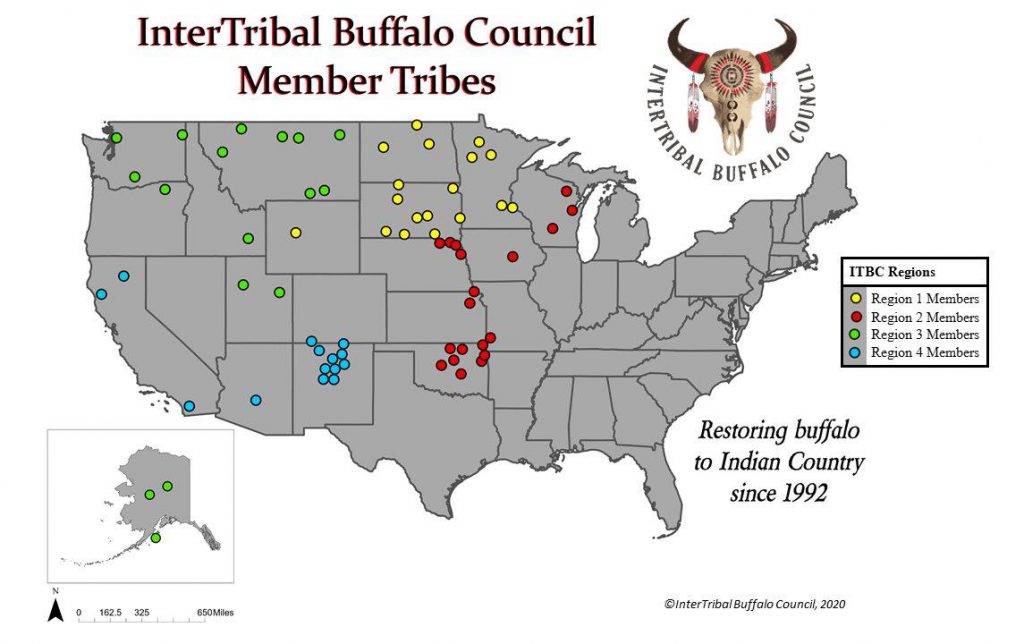

40 Bulls shipped to 16 Tribal herds

Then in August 2020 transfers were announced for 40 young Fort Peck buffalo bulls declared brucellosis-free by the state of Montana and the US Department of Agriculture.

At last, they were cleared for travel and slated for donation to 16 buffalo tribal herds in nine states.

Fifteen bulls were sent out to the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, Prairie Band Potawatomi, Modoc, Quapaw, Cherokee and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

A few days later more bison were hauled to the Blackfeet, Kalispell Tribe, Shoshone Bannock Tribes, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Oglala Sioux Tribe, Forest County Potawatomi and Oneida.

Logistics for two more tribes were still being worked out.

Arnell Abold, an enrolled member of the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe, is the InterTribal Buffalo Council’s Executive Director. She says this moment is a celebration for tribes, the National Park Service and the state of Montana.

“This is huge for us, and we’re eternally grateful and humbled by this moment, and we look forward to putting more animals back on the landscape and returning them to their homeland,” Abold said.

Megan Davenport is a wildlife biologist with InterTribal Buffalo Council.

“Tribes have been advocating for the last 30 years, particularly with this Yellowstone issue, that there’s a better alternative to slaughter,” Davenport said.

These animals marked the second transfer of bison from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation’s quarantine facility to other tribes, she said. The first was five bison sent to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

On Dec 12, 2020, Ervin Carlson, of the Blackfeet tribe in western Montana, writing for ITBC as board president, reported on how it all this came about.

“It’s been 27 years since ITBC submitted the first proposals to quarantine and transfer Yellowstone buffalo as an alternative to their slaughter,” he said.

“It’s been only four months since this has been actualized, with the first tribe-to-tribe transfer of 40 brucellosis-free Yellowstone bulls sent from Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes’ quarantine facility to 15 native nations through ITBC.

“While this is a massive victory and testament to 30 years of inter-tribal efforts to protect the Yellowstone buffalo, it has not been achieved without significant challenge.

He explains that in 1992 tribes were denied a seat at the table in the process of drafting the environmental impact statement for considering management alternatives for Yellowstone buffalo.

“Despite denied participation, ITBC persisted, introducing proposals and resources to develop a quarantine program.”

In 1997 ITBC submitted their first proposals to build quarantine facilities on tribal lands.

“This achieved overwhelming support from public citizens, nonprofits and federal agencies, though roadblocks persisted.

“ITBC finally won a seat at the Interagency Bison Management Plan in 2009 to protect and preserve the Yellowstone buffalo.”

“Due to the dedication of the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux tribes, and the 30 years of arduous activism by ITBC, the tribes completed construction of their quarantine facility in 2014.

“This facility was built to accommodate all phases of quarantine and can handle approximately 600 buffalo on 280 acres surrounded by double fences.

“With the assistance of ITBC, the tribes continue to improve this facility by expanding the number of pastures through cross fencing, increasing the capacity for additional groups of buffalo.

“The construction of this facility was initiated upon the request of the National Park Service.

“The Fort Peck quarantine facility is still not used to its full potential because a Montana law and federal regulations are misapplied to the tribes.

“The capacity of the facilities in and near the Park are not adequate to allow new groups to enter the quarantine program each year resulting in a larger number of buffalo being slaughtered. These facilities cannot accommodate as many buffalo as Fort Peck.

“No animals will enter the quarantine program this winter.

“Each winter, buffalo migrate outside the boundaries of Yellowstone, and either face capture and shipment-to-slaughter (442 animals last winter) or hunting by tribes utilizing treaty-secured rights (284 animals last winter).

“Because there is limited capacity in the facilities in and near the Park and a refusal to use the Fort Peck facilities to their full potential, more buffalo will be slaughtered this winter.

“ITBC’s solution of quarantine and translocation, the alternative nearly 30 years in-the-making, helps offset the number of buffalo killed for migrating outside of the Park’s invisible fences.

“The buffalo that consecutively test negative for brucellosis for years within the program are transferred to tribal lands to preserve their unique genetics and restore Tribal spiritual and cultural relationships.

“They are the descendants of the buffalo our Native ancestors lived with for centuries, and are honored and revered by the many nations with whom they find a home.”

Ervin Carlson, ITBC’s President for the past 17 years stated, “ITBC appreciates the efforts of the state of Montana in supporting quarantine operations and is deeply grateful to the US Department of Agriculture, Yellowstone National Park and to the Fort Peck Tribes for their dedicated partnership in accomplishing this mission.

“Finally, this moment would not be possible without our Member Tribes’ years of participation, support, and tireless work to ensure that buffalo and Native people are reunited to restore their land, culture, and ancient relationship across North America.”

Testing and Quarantine Continue

Before shipping the Yellowstone Park buffalo out to other tribes the Fort Peck tribes did a final quarantine testing.

It was an unforgettable bright August morning in the northeast corner of Montana.

Robbie Magnan, Game and Fish director for the Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, rose before dawn to round up and ease the 40 buffalo bulls into closer corrals near the loading chute.

“There’s always been a lot of hoops that we’ve had to jump through, and it’s something that we’ve just worked diligently for a lot of years to get this far for this happening today,” said Carlson.

“So today is real gratifying, just to be able to get some animals out of [the park] and to tribes alive.”

“We have a drum group out here. They’ll sing the prayer songs to send the buffalo safely to their new homes, that they travel safe and receive blessings and say goodbye for us, and we’ll send them on their way,” Jonny BearCub Stiffarm says.

You’ll notice here at this gathering that there’s some real little children. Buffalo will always have been a part of their lives,” BearCub Stiffarm says.

“And so for a lot of us older generation, to be able to see that circle become complete has really been meaningful.”

If you’re experiencing quarantine fatigue, these bulls can relate, their handlers say.

“These guys have been in there for years,” Magnan says. “Most of their life they’ve been in some type of quarantine.”

They endured two years of quarantine at Yellowstone National Park, where they started their lives, before being transferred to Fort Peck for final years of isolation and disease testing.

“But today is a good day, because they’ll go to a home where they’ll never have to be tested again,” Magnan says. “And they have the rest of their life to enjoy being a buffalo.”

Their new homes are as far from here as Kansas, Wisconsin and Alaska. It was to be the largest ever inter-tribal transfer of buffalo.

A semitrailer backs up to the chute to start the first ones on their journey.

It takes two hours and lots of commotion for a group of tribal Game and Fish employees, plus a handful of community volunteers, to coax the 2,000-pound bulls through the chute and onto the trailers.

The Cherokee continue to work with the Council, which awards surplus bison from national parks each year to its member tribes, and hopes to obtain another 25 or 30 cows.

The two young bulls, each between 1,000 and 1,500 pounds, were trucked over 1,000 miles to Delaware County, Oklahoma this week.

Both animals managed the stress of the trip well, said Cherokee Deputy Chief Bryan Warner. They were at first held separately from the others in the herd to be slowly introduced into the population.

The two bulls will put on hundreds more pounds each to reach their massive 2,000-pound adult size, and in the meantime they will find their place in the hierarchy among other bulls and eventually reproduce naturally among the herd, he said.

As descendants of the buffalo that once roamed free more than 100 years ago, the new genetics bring a lineage to the herd welcomed in more ways than one, he said.

“Yellowstone buffalo are significant to tribes because they descend from the buffalo that our ancient ancestors actually lived among, and this is just one more way we can keep our culture and heritage and history alive.”

“This partnership with the InterTribal Buffalo Council continues to benefit the Cherokee Nation by allowing the tribe to grow a healthy bison population over the last five years,” Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr said in a press statement.

“Historically, bison provided an essential food source for tribes. Every part of the bison was used for food, clothing, shelter, tools and ceremonial purposes. These newly acquired bison will help revive some ancient cultural traditions, as well as provide expanded economic opportunities for future generations of Cherokees.”

Although bison are associated more with the Great Plains tribes, wood bison once roamed the Cherokee lands and all along the Atlantic Coast. Prior to European colonization, the animals played a critical role for the Cherokee people as a vital food source.

Until 2014, the Cherokee had not raised bison for 40 years. After spending two or three years working with the InterTribal Buffalo Council, the tribe’s herd now has about 180 bison.

Robbie Magnan says all this hard work is worth it to restore an animal that was once the center of life for many tribes across the Great Plains and Mountain West.

Along with other long-time workers in ITBC he believes contemplating a herd of buffalo can bring Native tribal members a sense of peace, love and strength in dealing with life’s problems.

The ITBC and the Fort Peck Tribes say this is the first of many large inter-tribal buffalo transfers out of the quarantine program.

This winter, they plan to transfer 30 to 40 animals, an entire family group, to one lucky tribe that can prove it has the resources to care for them.

Come spring, the ITBC is expecting a new shipment of buffalo from Yellowstone National Park to the Fort Peck Reservation.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog