Part 2: Hunting Calves with Buffalo Jones in the Desert, 1887

In the 1880s, the last southern buffalo hid in the remote, distant areas of the southwest, protected from hunters by drought and the forbidding sands of the desert. It was there that Buffalo Jones set out with two wagons and crew determined to capture and save buffalo calves.

Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an American author best known for writing western stories and historical novels. He earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1880 from the University of Iowa, then studied law and was admitted to the bar.

He and a friend, the artist J.A. Ricker, arrived in Garden City Kansas just as Buffalo Jones prepared for his 2nd expedition to capture buffalo calves in remote desert regions of Texas and the southwest.

The young men had been told that a wild herd of buffalo was within 200 miles to the south.

“We had supposed that the last buffalo had been killed. . . The event of a lifetime to see them!

“It was our last chance!” wrote Hough.

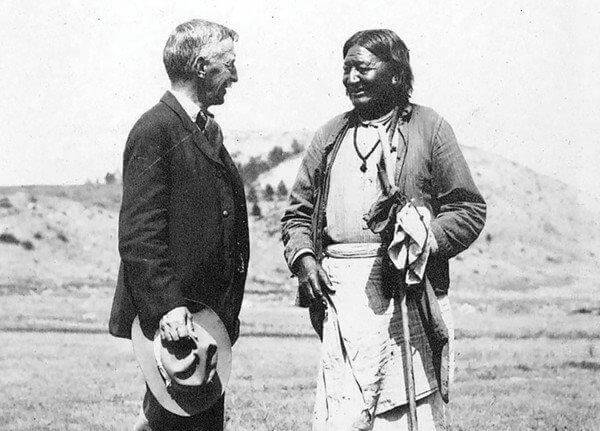

They met with Buffalo Jones—who first refused them as he had “50 less determined beggars.” But apparently, he could not resist the willingness of the eager writer and artist to record his trip.

“He smiled amusedly, looked us over, made us promise not to grumble if the bread was burned, and finally said, ‘Gentlemen if you will obey orders and not shoot or scare the buffalo in any manner without permission from me, I will take you in.’

“All of which we swore would be carried out faithfully.

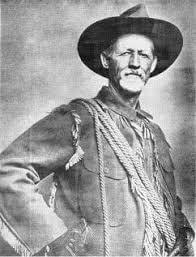

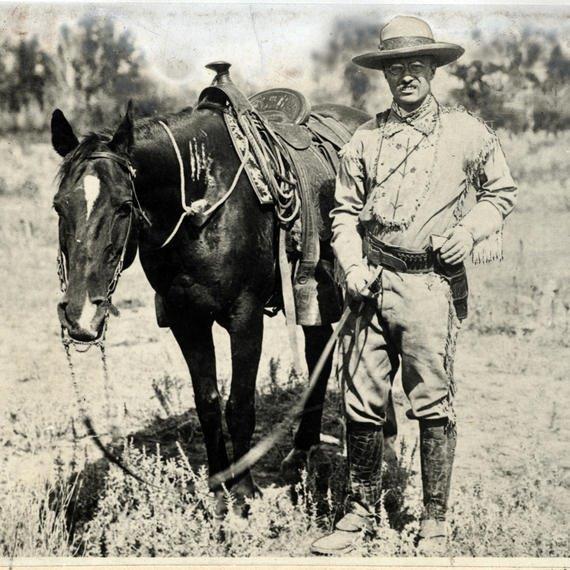

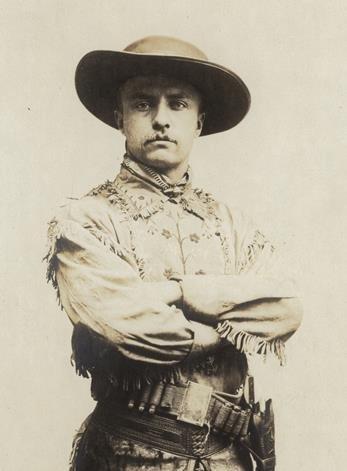

“And now we must tell about Mr. Jones, for without him such a hunt—or the pleasures of it, or the story of it—could not have been at all.

“The Hon. CJ Jones is ‘The gentleman from Finney,’ when he is in the legislative halls at the capital of Kansas, but when out of his legislator’s desk he is just ‘Buffalo Jones’ . . . well-known all over Kansas and the West.

Buffalo Jones, “well known all over Kansas and the West”—plainsman, buffalo hunter, mail carrier, town builder and rescuer of buffalo calves—his goal to “preserve the species.”

“He had built a city, made a fortune, located the townsite of Garden City, ‘one of the liveliest and loveliest towns in western Kansas.’

“In the 70s he was out west in Kansas, away ahead of the rain belt with little to support him but his belief in the future of the country, his ability to ‘rustle’ and no doubt the hope of a blessed immortality if he starved to death. He was mail-carrier, station agent—anything he could be.

“In those days Mr. Jones lived in the heart of the buffalo country and in the midst of the buffaloes. He grew fundamentally acquainted with the animals and learned their every habit.

“Let it not be misunderstood—he did his full share toward exterminating the buffalo . . . but even as he destroyed them, he grew to know them and regret their fate.

“And as they faded away from the range and it became certain that soon they would be gone forever, no heart was fuller of regret than his and no mind so full of expedients to rescue them.

“His goal was not to destroy, but to preserve the species by saving buffalo calves.

“So we were to be in at the ‘last roundup.’ To see a buffalo had been our highest wish.”

Jones’ party set off in 2 outfits—a heavy wagon with 3 men had left the railroad for the south a week earlier, with the camping supplies and tents and over 2,000 pounds (a ton) of grain for the horses. He noted that preparations for the trip had cost him over $1,000.

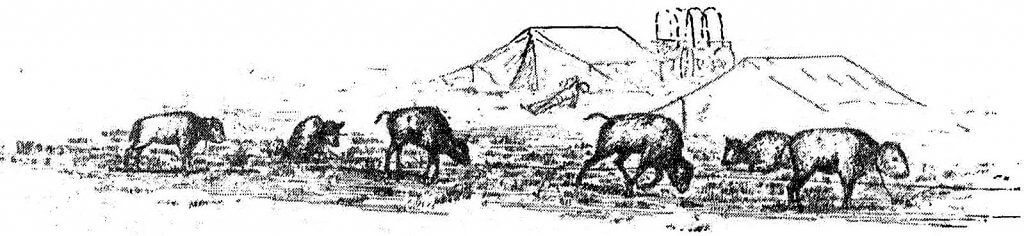

Scenes on the journey. The heavy wagon (shown here in sketch by JA Ricker), left a week earlier with camping supplies, an extra team and 12 milk cows to furnish fresh milk and “mothering” for the buffalo calves they hoped to capture.

“The heavy wagon had a mule team, an extra team, three running horses—Jennie, Kentuck, Mr. Jones’s favorite Kentucky horse, and a black horse we christened Blackie.

“Also 12 milk cows without their calves, which meant they could not travel more than 20 miles a day.”

The livestock were in charge of Charlie Rude—the man Buffalo Jones always “banked” on. He had been on the first calf hunt the year before, and “knew the trail and the points to make for.”

The lighter wagon made 80 miles the first day into the desert, and camped for the night in the valley of the Cimarron. Between rocky bluffs on one side and gray sandhills on the other.

They found the wagon trail, met some cowboys with a ranch wagon who were picking up buffalo chips for fuel.

From the cowboys, they learned their other wagon had camped 6 miles below the night before. Only half a day ahead. About 2 o’clock they sighted them through field glasses and pushed on till they caught up with them.

Ez Carter had killed an antelope buck the day before. Not yet 18 years old, he was known as a plainsman of experience and one of the best ropers on the range.

“We found all the boys jolly and enthusiastic over the hunt. Stock well-watered from the buffalo wallows, filled from a recent rain,” reported Emerson Hough.

“Hobbled horses, pitched the tent. Ate a supper fit for the gods.

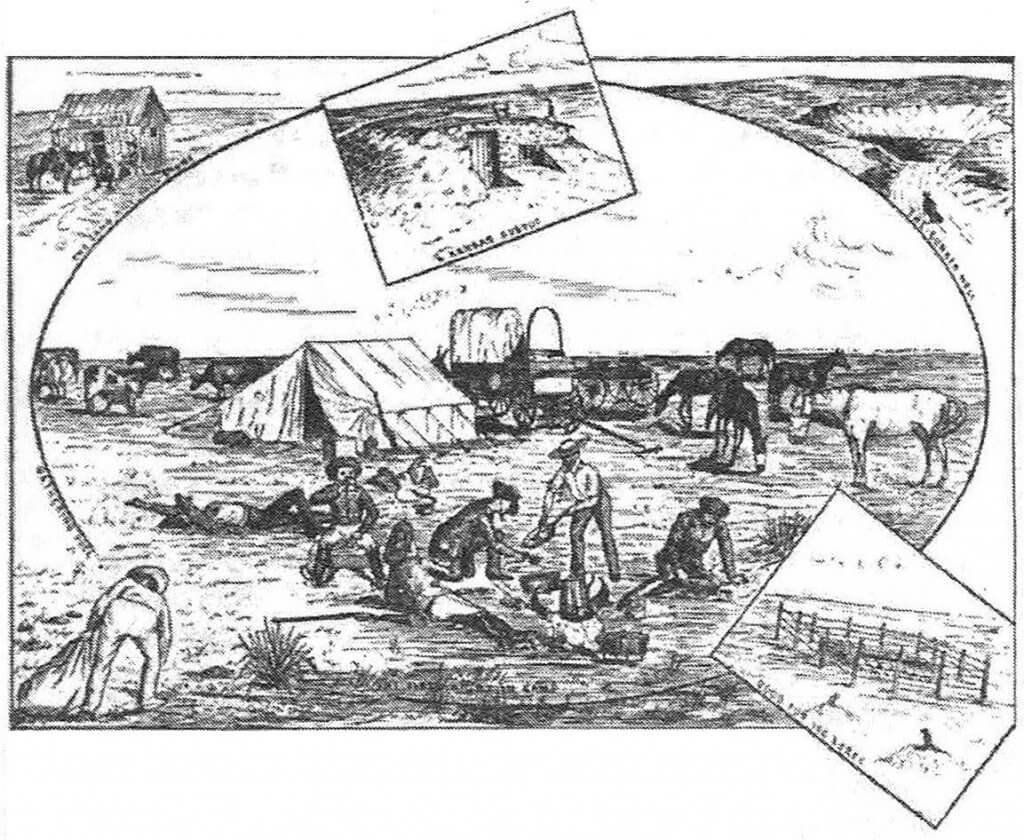

The full camp. They made 80 miles in one day and caught up with the other wagon. That night their camp was “busy and jolly” at the edge of civilization. They ate an antelope supper “fit for the gods.” Colonel Jones and Ez practiced their roping skills during which anyone was “likely to lose a hat or be tripped up by the heels, while the Greyhound, Don, was roped so often he howled whenever he heard the whiz of the lasso.” Credit JA Ricker.

“Our tent that night was a busy and jolly one. Colonel Jones and Ez began to practice with the lasso, in order to work up their skill and muscle for the coming trial on the buffalo calves.

“During their drill hour we were any of us likely to lose a hat or be tripped up by the heels, while the Greyhound, Don, was roped so often that he howled whenever he heard the whiz of the lasso.”

That night a heavy wind came up and blew down the tent.

Next day they ate at the Anchor D ranch—“Pretty near the ‘Jumping-off place of the world.’

“Now about 150 miles from our starting point, well down where we might expect to see or hear of the buffalos.

“But could get no news of the herd. They “might be at a point known as Company M, or down on the Agua Frio,’ or there might be water enough along the San Francisco to hold them, or out on the Flats, at some waterhole known only to themselves . . .

“We were not surprised, for we knew that cattlemen would not tell us of the herd if they were within 10 miles, and Colonel Jones says he always finds buffalo in the opposite direction from that advised to go.

“Therefore, our leader was not in the least put out by this general blankness in regard to the buffalo.”

Being now some 30 miles in advance of the slow-moving heavy wagon with the milk cows, they left instructions with cowboys at the ranch for the rest of their party to pitch camp on the upper pools of the Beaver while they went scouting ahead for buffalo with the lighter vehicle.

Buffalo—Running against the Storm!

Finally, one morning during a rain storm they saw—far off to the left—a small bunch of rapidly moving objects.

“As soon as he saw these animals through the glasses, Colonel Jones gave an exclamation of surprise.

“ ‘Why, they’re going against the storm!’ and a moment later added, ‘Yes, they’re buffalo, sure!’”

The animals were three or four miles distant, and the rain made everything obscure, although it could be seen they were running furiously and directly into the wind.

“Boys,” said Mr. Jones, “Those are buffalo. The buffalo is the only animal that ever runs against a storm. Cattle or horses drift before it, but a buffalo, never.”

”The animals came within a mile and a half and at last we could really say we had seen our first buffalo. We could see the humps plainly and how low they carried their heads as they went on in their tireless, lumbering gallop.

“There were only three—a cow, a yearling and a calf. We were half frantic to get at them, but Mr. Jones refused to tire the horses by a chase after so small a number. We begged Colonel Jones to turn back, but he assured us we would see plenty more.

“We crossed Tepee creek, finding some water in pools near the trail.

“The sun was getting low, and we were trundling along at the base of the breaks when our eyes were caught by a cloud of dust rising from the other side of a little ridge. We snatched up the glasses. The cloud came nearer. It swung up over the crest.

“Huge black forms—20, 30, 50, 60—rolled and surged along with it, heading almost toward us. No need for glasses now. Our tongues ‘froze stiff,’ until a second later our leader sprang clear of the buggy at a single bound and shouted in a voice like a bugle.

“’Get out the horses! They’re buffalo, by Jupiter! Give me the lasso!’ “

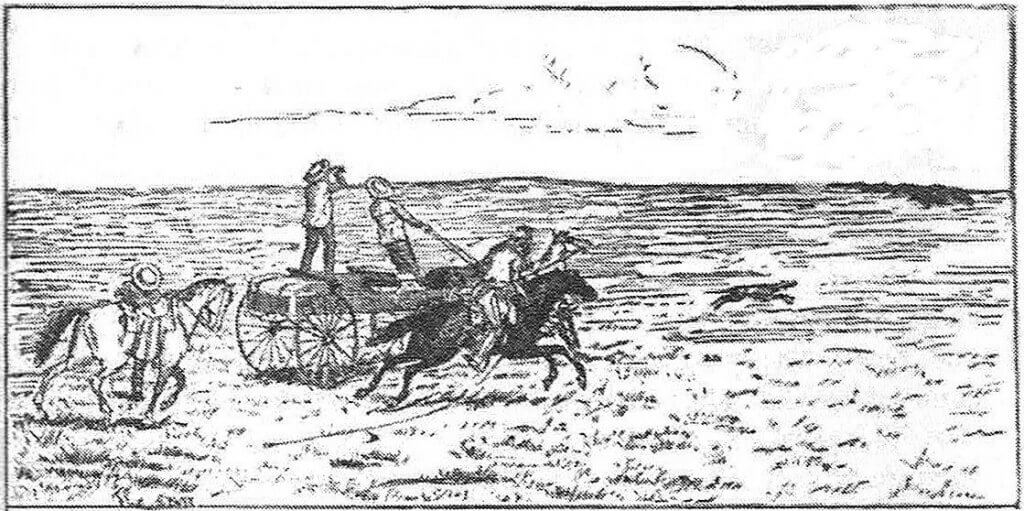

In seconds Colonel Jones and Jennie sped ahead—the mare seemed to fly.

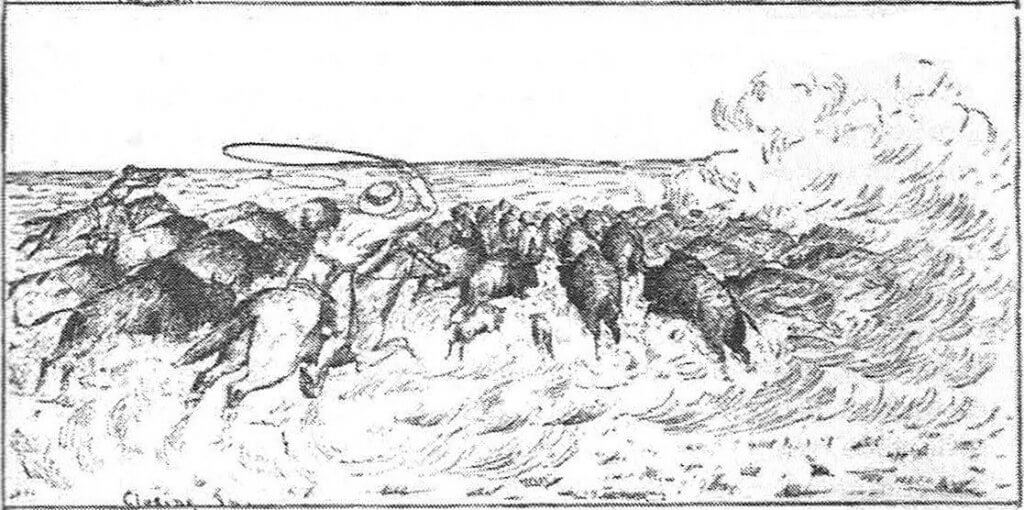

“The sight was a grand one. With head well down and nostrils wide, the bay beauty tore in on them, eager as her rider and was never once called on with the spur. She crowded into the dust, into the herd, pushed out from it a cow and calf and lay alongside of them in her stride,” wrote Hughes.

The mare Jennie “eager as her rider, crowded into the dust, into the herd, pushed out from it a cow and calf and lay alongside of them. . . In a flash the dust was gone, and there was Colonel Jones kneeling on top of a struggling little tawny object, while Jennie stood by looking on complacently.” JA Ricker.

Then we saw her rider lean forward. Up came his hand, circling the wide coil of the rope. We could almost hear it whistle through the air. The next instant out it flew.

“In a flash the dust was gone, and there was Colonel Jones kneeling on top of a struggling little tawny object, while Jennie stood by looking on complacently.

“A second later the little object was hobbling around upon the grass alone. Colonel Jones was following young Carter now and we were making for the calf.

“The herd at once swept out of sight and we drove up to the first victim. He was a comical looking, round-headed, curly little rascal. We laughed when approaching him. The first thing he did was to utter a hoarse bawl and charge at us with head down.

“In doing this, of course the hobble tripped him up and he turned a somersault.

“Before he could recover, we sat down on top of him—the first buffalo calf we had ever seen. We found that he was secured in precisely the best and most effectual way that could have been devised.

“The hobble was made of several strands of untwisted rope. At the middle it was tied in a large loop, which was slipped over the calf’s head.

“The two loose ends—which were left at just that length which experience told was right—were slip-noosed. These loops were fastened just above each hind foot, where they sat tight on the pastern joint, and drew the tighter for each struggle the calf made to free itself.

“Thus shackled, the captive was unable to make any progress, but at the same time was not choked or held in any way to injure it.

“Of course, adjusting the hobble took but an instant.

“And that was necessary—for even after the delay of a minute the herd would gain ground enough to make them hard to overtake.

“As we afterwards learned, Carter and the gray horse got into the edge of the herd easily enough, but his horse could not be pushed in close enough for roping, as he was afraid of the buffalo.

“Carter spurred and quirted him in vain. He was just the same old ‘gray devil’ and needed the stay-chain.

“Carter was furious at his inability to reach a calf. Colonel Jones again passed him and went into the herd within two miles of the place where the first calf was caught.

“He missed his cast at the next calf, but the mare did not stop.

“As she ran alongside of the now angry animal, Colonel Jones stooped down and caught it by the tail, turning it heels-over-head, and before it could rise the Colonel was on top, held it in his arms, and then hobbled it.

“This was a large bull calf, the largest taken on the entire hunt and he made a big fight after his fall. The calf was like a basketful of eels to hold.

“The last calf was caught by Carter, who roped it neatly as Colonel Jones cut it out of the herd and turned it toward him. This was a fine heifer calf, apparently the idol of her mother’s heart, for the latter came very near making a casualty the price of the capture.

“As soon as the calf was roped, the cow left the herd and charged Carter viciously as he bent over his victim.

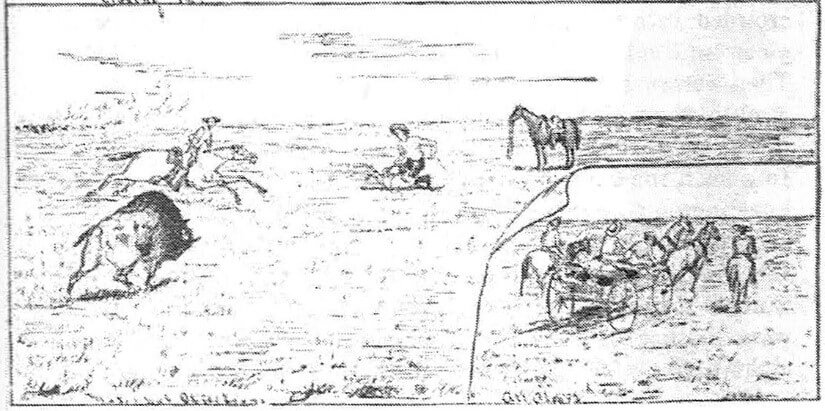

The mother left the herd and charged toward Ez Carter as he hobbled her buffalo calf. Colonel Jones rode up just in time and drove the cow off—but only for a moment. She continued to charge and regretfully, he shot and killed her with his revolver. Corner sketch shows the light wagon. JA Ricker.

“Seeing this danger, Colonel Jones rode up just in time and drove the cow off for a moment. But she returned again and again and finally began charging at him whenever he came near, so that, much as he regretted it, he was compelled to shoot her with his revolver, killing her almost instantly.

“This was an unwished result and was much deplored, for we came, not to slay, but to rescue.

“After this, both rode on after the herd, which was by this time far toward the darkening horizon. The horses were now well blown, for they had run in the herd not only once, twice, but three times, and had gone a distance of 8 or 10 miles from the start.

“Colonel Jones soon pulled up and turned back to find the wagon.

“In the meantime my companion and I had, by dint of severe exertion, got the first calf tied up more firmly and secured in the light wagon, where it required all our strength to keep it until we devised the plan of piling the heavy tent upon it.

“We then drove on along the trail, using the glass all the time to sight the next captive, which we presently did, at a distance over a mile from us.

“We repeated our tactics here, having a great time with this big fellow; then drove on, meeting Colonel Jones before we got to the last calf. As it was possible and quite easy to miss seeing so small an object at such long distances, we were glad to learn that we had found all that had been caught.

“It was nearly dark by the time we had the last calf in the wagon, and as soon as Carter came up, all started back toward the Beaver.

“We could not camp, for we had no water and the horses needed it sadly.

“As there was none elsewhere within 20 miles, it was absolutely necessary that we find the river. It should be remembered that this river had no water in it, except at certain places. And we did not yet know where those places were.

“We might have to drive 20 miles after getting to the riverbed and might have to travel nearly that far in trying to get down through the breaks which fenced in the stream.

“All this was pretty near to being serious. But it was one of the demands of buffalo hunting.

“So we said nothing, but turned in the direction where we knew the stream lay, and ran by the compass and the stars, driving in darkness which grew more dense at every moment.

“If our leader had been a man inexperienced on the Plains, or unacquainted with the general lay of the country, we would have had a dry camp that night, and would in all probability have lost our calves, to say nothing of any possible discomfiture to ourselves, or injury to our horses.

“In an hour or so we came to the edge of the breaks, and began to hunt a way down through them.

“Richter and Carter rode off to the right, while Colonel Jones drove a little to the left. We noticed that all the trails appeared to converge at the head of a certain draw, and after driving across them till that fact was established, we knew that they led to water.

“We therefore followed down this draw, and fired signals for the boys to come in.

“Presently we heard Carter fire, he having got out on a point at our left.

“Ricker had not come in, and did not answer any signal. Fearing he was lost, Carter went back after him.

“Colonel Jones and myself, following the draw, presently got into the valley and found water. There was not much, and it was tramped up by cattle and had several dead carcasses in it.

“But still it was water, and we were glad to find it.

“By the time we had the horses out and the baggage on the ground, Ricker and Carter got into camp, the former insisting that he was one of the sort that didn’t get lost.

“We all fell to and proceeded to water the horses and get camp up. We found there was no axe or hatchet with us, but were lucky to find a hard stone, with which we drove our tent pins—for it looked like rain.

“We had no coffee mill, but an old buffalo skull, a bit of canvas and the stone served instead.

“Presently the clouds broke, and the southern moon peeped out brightly. It revealed another pool of water below us, and we could see a bunch of ducks upon it. As we had not stopped to butcher our buffalo, we had no meat, so Ricker took his three-barrel and shot four ducks, which Ez Carter fished out with his lasso.

“When we went down to the water we heard something flopping and discovered it was fairly alive with bullhead fish. We therefore supposed that the running water could not be very far away. A search soon revealed that a succession of pools began a short distance below our camp.

“Then as our little fire of chips was going nicely, Ez soon had some bread baking, the coffee pot simmering and some bacon and skinned teal sizzling in the frying pan.

“Our stove was a buffalo skull and our shovel a shoulder blade. No Man’s Land is entirely devoid of timber, and even of small sticks.

“While we were getting supper and arranging the tent, Colonel Jones was busy with the calves.

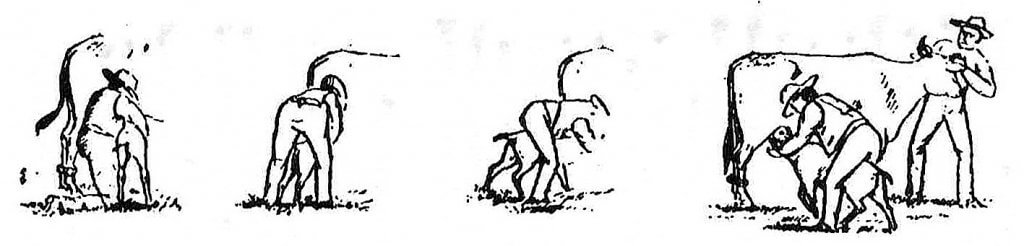

Jones stretched a long rope on the ground, fastening the ends to two tent pins driven in the ground. Then he strung the calves “like fish on a trot-line,” tied by the neck. “The little fellows were vigorous and full of fight.” JA Ricker.

“Taking a long rope, he stretched it along the ground, fastening the ends to two strong tent pins driven to the head in the ground. On this rope he strung his calves, like fish on a trot-line, each calf being tied by the neck and with its limbs left free.

“This arrangement gave them plenty of play and kept them from injury, while at the same time it rendered their escape impossible. The little fellows were vigorous and full of fight, and whenever anyone came near they would lower their heads and come at him with a short bawl.

“We amused ourselves by pushing each other upon them, and found by experience that they could butt hard enough to knock a man entirely off his feet.

“They spent most of their time standing with head down, back humped up, and tail cocked out, pawing the ground for all the world like an old bull, and from time to time uttering short, hoarse bawls, that sounded more like the grunt of a hog than the bleat of a calf.

“We sat beside them after supper until a late hour. Then we rolled up in our blankets and went to sleep, telling each other that we were the luckiest fellows in all the world.”

Next morning, May 14, all were up early, checking on the calves.

“We feared we would lose all our calves before the main outfit arrived, for we had not a cow with us, of course, and not even a can of condensed milk.

“All that could be done, was to try to induce our panting and suffering little captives to drink of the water which we offered them. But they refused to be comforted, and indignantly butted the water pail endwise whenever it was left near them, or charged headlong at a wet rag or a stick.

“Colonel Jones concluded to go out and try to find the herd again, then to return, and in the evening either rope a range cow, or drive down in the night to meet our team and get some condensed milk to keep the calves alive until the domestic cows would arrive.

“Accordingly, he, Ricker and Carter started out with all the horses, directly after breakfast. It fell to my lot to remain and guard the camp—which I did not relish very much.

“At 3 pm our scouting party returned. They had not found the herd, but had met two buffalo cows, undoubtedly the mothers of the captured calves, whose maternal instinct had led them to return in search of their offspring.

“One cow was killed for meat. Her udder was full of milk, and as there was no water to be had, the Colonel filled a canteen. After milking the canteen about half-full he corked it up and tossed it into the spring wagon.”

Unexpectedly, the milk churned itself into butter in the hours of driving, which the men salted and drained.

“We had one grand feast of hot biscuits and buffalo butter! It was declared delicious when enjoyed with hot biscuits.

“No water could be discovered anywhere. The flats were entirely dry.”

Jones rode his horse down the Beaver hoping to meet the other wagon team.

“Giving neither himself nor his horse any rest—for it was imperative that we get milk, or we would lose our calves.

“The little fellows began to look gaunt, their tongues black and swollen, hanging from their mouths, while they continually uttered their hoarse, growing grunts of complaint.”

It was a couple of hours after dark when they heard repeated yells and shooting. They replied and soon the others came up with the wagon and cows.

Jones had found the wagon just in time or it would have stayed up on the flats, probably passing by and wandering “no one knew how far into the waterless country.”

“Everything was now confusion in camp. We had a great many animals to take care of and it necessitated work.

“The cows had all to be lassoed and hobbled—which they resented. The horses to be watered. Supper to cook, and a hundred other things to be done.

“One of the first of these duties was feeding the buffalo calves. And this was one of the most interesting features of the whole hunt.

Mothering the Buffalo Calves

“Ez roped a certain old red cow of about the right color as any we had, and hobbled her securely fore and aft. Then we picked out the youngest calf and approached—the little fellow butting and fighting viciously.

“The cow turned her head and promptly kicked so hard she broke the hobble and sent the calf a somersault. It was strange, but after a few moments this cow and buffalo calf seemed to ‘take to’ each other. And within an hour the curly little rascal was lying down by the side of his new mother, chuck full of milk and happy as a clam.” JA Ricker.

“The cow turned her head and promptly kicked so hard she broke the hobble and sent the calf a somersault. This did not daunt it, however, and it returned, seeming to take in the situation at a glance.

“It was strange, but after a few moments this cow and buffalo calf seemed to ‘take to’ each other. The best of relations were established between them.

“And within an hour the curly little rascal was lying down by the side of his new mother, chuck full of milk and happy as a clam. This calf was never wild after that, but could be approached easily and was perfectly docile.

“In the morning we let it loose near the cow and it followed her about, kicking up its heels and bawling out of very exuberance of spirits.

“The next day, the cows were hobbled and the calves’ lariats allowed to drag loose, yet they never made any attempt to escape. Today the little calf is the tamest on Colonel Jones’ ranch and the old red stripper (as she is called, for she has had no calf of her own for three years) is its devoted mother.

“This cow took a great notion to all the buffalo calves and would allow two of them to suckle at once, though she would drive off a domestic calf. The buffaloes were emphatic, imperious little scamps, and she seemed to take a fancy to them.

“The other calves gave some trouble. They did not take kindly to the white cow which was introduced to them as their stepmother, nor did she take to them.

“One of the calves preferred a beer bottle, covered with a rag.

“The big bull calf would drink from nothing but a bucket—though he made a very good supper in that way. And, it may not be believed, but he would never afterward drink out of any but that particular pail, which happened to be painted white outside and in.

Teaching the buffalo calves to drink was a challenge. They were “full of action and spirit,” pawing, butting and snorting “to make up a history of interesting experiences that never can be duplicated.” JA Ricker.

“If any other was offered him, he would butt it over at once and prance around pawing at the dirt, until someone would call out, ‘Give him the white pail!’

“The scenes of that night and of the succeeding days, in trying to teach the buffalo calves to assume their new relations, were full of action and spirit, and went to make up a history of interesting experiences that never can be duplicated.”

Both wagons next headed farther west with supplies for a week’s trip, leaving behind in the home camp all the cows and the buffalo calves, with Robinson to care for them.

They drove 50 or 60 miles, and then for 2 days scoured the country for 50 miles around to find some trace of the buffalo herd. Constantly they studied the horizon with “powerful field-glasses.”

“We found but little water, but dug a hole in the sand and got enough for our use.

“We began to be discouraged—all except our leader, whose resolve to find the buffalo herd seemed never to flag.

“One morning just as the sun was rising we saw a little bunch of animals slowly walking toward us, about two miles distant and on the other side of a wire fence.

“We turned the glasses on them. They looked like buffaloes. We studied them.

“They looked wonderfully like buffaloes . . .

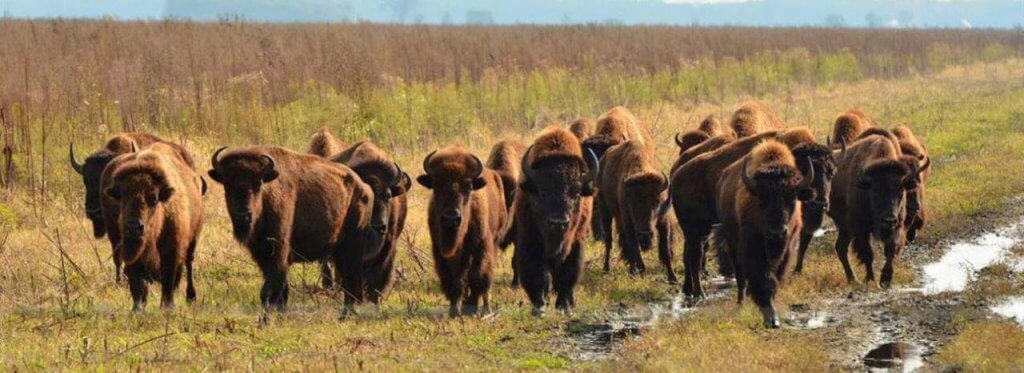

“Colonel Jones fired a shot toward them. At once they strung out into a line and tailed off as hard as they could go. Cattle do not run at the sound of a gun. Buffaloes always do—a habit acquired since they have been hunted so much.” NPS, Harlan Kredit.

“We divided in our opinions. Colonel Jones thought they were buffaloes. But we did not wonder at that, because he thought everything he saw was a buffalo. Ez didn’t know. Charlie didn’t care. Ricker was not certain. I knew all the time they were only cattle.

“Finally, Colonel Jones fired a shot toward them from his rifle.

“At once they strung out into a line and tailed off as hard as they could go. Cattle do not run at the sound of a gun. Buffaloes always do—that is a habit acquired since they have been hunted so much.

“In a moment Colonel Jones and Ez Carter were in saddles and racing ahead, with Ricker and myself a good second in the light wagon and Charley following with the mule team after the dust cloud.

“We all got across the wire fence, I don’t know just how, and followed after the dust-cloud.

“The wagons were far behind when, after a half-hour’s breathless drive, we saw a horseman appear on the crest of a distant ridge.

“He gave us the Plains signal to ‘Come ahead’—which is by riding at right angles to those called if mounted, or by repeatedly rising and squatting down if on foot.

“We hurried on and soon by the glass made him out to be Ez Carter and saw that he had at the end of his lasso a lively red object we knew to be another buffalo calf.

“Ez came riding down on a gallop, the calf running parallel with the rope stretched tightly. This was the curliest calf caught on the trip, and a fine prize she was.

“Ez had lost his hat and we learned that Colonel Jones had gone back along the trail to find it and his field glass, both of which were found.

“The calf was caught under rather peculiar circumstances. Both horsemen were crowding it. Colonel Jones cast for it, but it dodged the noose and ran square in front of his horse.

“The calf ran against it and both fell, knocking it fully 15 feet away and throwing Colonel Jones headlong.”

Jones, according to his version, was satisfied as he passed through the air that the fall would kill him, but concluded that it would be as well to go into another world with a calf in his arms as in any other way!

“He fell directly on top of the calf, caught it in his arms and held on until Carter roped it. It was a ludicrous and altogether lucky accident. Neither man, horse nor calf seemed to be much injured.

“We bundled the calf into the big wagon and headed northeast in the direction of our main camp, through terrible sandhills which made rapid travel impossible.

“The day was very warm. We gave the horses all the water left and started on with many misgivings.

“We did not stop for dinner, but spent our time trying to find out where we were.

“And, thanks to fortune and hard driving, we at last got up to a little mesa which was familiar and soon struck a trail and better country for traveling.

“We were truly thankful that our leader was not a tenderfoot, for such had best not go hunting in that country, unless he wants to die crazy and bleach his bones among the sandhills.

“We came upon a ridge and our white tent lay before us, a thin blue shaft of smoke piercing the sultry evening air.

“The water pool shone in the evening sun and the cattle were grazing about it or lying near.

“Our jaded horses pitched their ears forward and actually broke into a trot.

“The long and wearisome day was over. We were thankful that the day had been no worse.

“The mule team with Charley and Ez came in late.

“During our absence one of the calves had died—the only heifer calf we had, and therefore most valued of course.

“This made us feel sad, so on the whole it was rather a demoralized crowd of hunters that gathered around our late supper that night.”

They stayed in camp a day or two to rest the horses “which were well-nigh broken down under the severe tasks which had been imposed upon them.”

One afternoon the camp was out of meat and Jones went out on foot to stalk some antelope he saw coming in to the water.

They heard a shot and he came in at a dead run, calling out to Hough and Ricker, “Get out the horses, boys! Four bulls just ran out the other side when I shot! You’re going to have that shot at a bull I have been promising you.”

“He gave us the signal to come on and we galloped up to the top of the level country,” reported Hough.

“There four miles ahead running into the wind and looming up as large as churches in the streaming mirage which surrounded them were four huge objects—the buffalo bulls!

“The bulls were running directly from us and neither saw nor winded us. They fell into a walk.”

The men rode closer. Racing to a small hollow they left the horses and crawled toward a sagebrush that hid them.

“We made a big circle back and got the wind to suit us

“Now the skill of the old buffalo-hunter began to assert itself. We found he knew more in a minute than we did in all the rest of the year.

“We laid ourselves flat along the earth and inch by inch crept up to the edge of the shallow little basin in which the bulls were standing. “

They all shot, but the bullets went high. The bulls ran.

They shot again. The bulls kept going.

At just that moment a herd of 50 buffalo cows and calves showed up heading for the water, and the calf hunters dashed off to follow them.

At just that moment a herd of 50 buffalo cows and calves showed up heading for the water, and the calf hunters dashed off to follow them. Hough and Ricker—who’d been yearning for a shot at a buffalo bull—were left alone to stalk the four bulls—but without success. SDGGP, Chris Hull.

The two young men Hough and Ricker—who’d been yearning for a shot at a buffalo bull—were left alone to stalk the four bulls. They got some good shots but without Jones’ help, most of the shots went wild and they could not tell if any animals were hit.

They hiked back to camp, fed the calves, hobbled the horses and sat late into the night.

Meanwhile, far into the distance, the calf hunt went on. When the others returned, well after midnight they had “three more buffalo calves curled up in the bottom of the wagon.”

Bright and early the next morning Jones declared his decision to make one more foray farther south. He said it would be the last hunt.

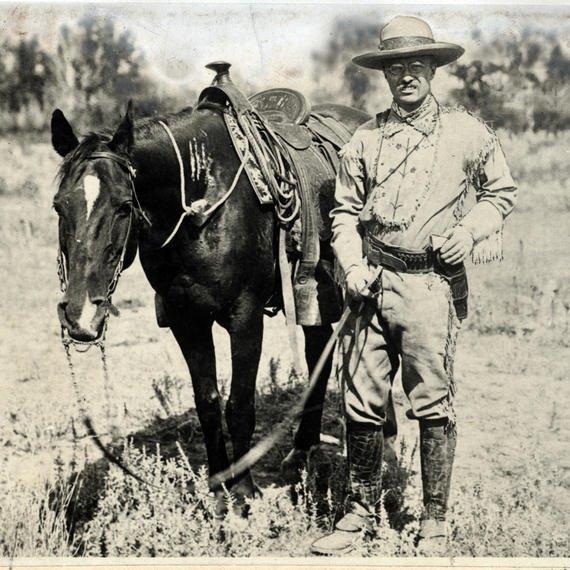

Before dark Ez Carter came in slowly leading the bay mare Jennie. Both were nearly dead from thirst and exhaustion. He threw himself on the ground saying, “I guess she’s sure gone!”

“The poor creature looked it truly. She stood with head down and legs wide apart, wet with sweat and trembling like a leaf. We soon found she was quite blind and blundered and stumbled about the camp.

“Then we poured a straight pint of raw whiskey into a pail. Before we could dilute it with water, the mare felt the rim of the pail, and at once drank its contents at a gulp.

“She drank that whiskey straight and it was the best thing she could have done.”

They gave her water and “she began to prick up her ears and whinny a little.”

“Then we knew she would pull through and we held a general jubilee, hugging the game old animal and calling her all sorts of pet names.”

“That mare’s clear grit,” said Carter. “She’s gone over 100 miles today and hasn’t had a drop of water. I’ve made three big runs on her and caught 5 calves without uncinching the saddle.”

Carter told them they made the first run for calves early that morning, and a second run late in the morning, and again in the afternoon. The horses were nearly exhausted and the day terribly hot.

The day was hot and the calves exhausted. So were the horses, but they made three runs—over 100 miles—without “a drop of water.” NPS, J Schmidt.

Jones had got so far away that it looked like he would have to leave his exhausted horse and try to make the 50 or 60 miles on foot.

But he found the trail and by driving his horse for a time—as it was so near gone it would not lead—and managed to keep it going until he sighted the wagon and signaled for them to come up.

The whole outfit was nearly “done up” and it was a question whether they would all ever get into camp.

But luckily Jones recognized a certain table-rock, and knew that camp lay far below them.

“Had they gone up the stream instead of down, they would have lost all their stock, and would probably have perished themselves.

“A party going down on that range would be foolish to start without a thoroughly posted guide. They would get no game, and would stand a large chance of dying of thirst.

“Carter had come down to get a fresh team and take back such water as he could.

“Poor fellow! He looked weary enough himself. But he did not tarry and after his hasty supper started back with the spare team, carrying as much water and whisky as he could sling about him in canteens.”

About midnight the rest of the party rode silently into camp.

The next morning Jones announced that he, Hughes and Ricker were heading home immediately and prepared the light wagon and for the trip, leaving the wearied stock for the heavier wagon to collect and bring.

“Our hunt was over!

“By driving day and night—we held our way steadily and, almost before we knew it were at the railroad and home in Garden City.

“Once we drove 100 miles in 24 hours!”

Even though they were disappointed not to finish their hunt for bulls, Emerson Hough marveled at his and Ricker’s good fortune in having their experience of hunting buffalo in the desert with Buffalo Jones.

He summed up their success with the calves.

“Today in the pasture at the edge of Garden City, Colonel Jones has 11 buffalo calves. Four of them are yearlings, fat as seals, shaggy as sheep, and so tame that you can almost touch them.

“The other 7 are the calves of this year’s hunt. They are lively as crickets and run bawling after their foster mothers like any other calves. The ‘old red stripper’ supports two and watches them with the most motherly pride.”

Hughes asks himself whether others could have succeeded as well—without the likes of Buffalo Jones.

“Could not the calf-hunt be duplicated by other parties? Could a party of hunters not acquainted with the country go into that region with any chance of success?” he speculates, then answers his own question.

“No. It would be dangerous to try. Water is too scarce. The path of the hunt might be a ‘journey of death.’

“It is probable that we were the last—or very near that last—civilized hunters to look upon the buffalo wild on its native range.

“It will be the cool, calculating, fiendish skin hunter who will make the last stalk.”

Hear his boasts, “I’ve got the last!”

“Poor fool!”

Buffalo Jones’ several trips into Texas deserts to save buffalo calves are compiled from his journals by Col. Henry Inman in the book Buffalo Jones’ Forty Years of Adventure by Charles Jesse Jones, published in 1899. However, this 2nd hunting trip is described in Jone’s book by E. Hough, with drawings by J.A. Ricker, two young men who pleaded to be taken along.

(See also our earlier Blog: Part 1: Hunting Calves with Buffalo Jones in the Desert, 1886).

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

A small stone, which is often a fossil shell, or sometimes only a queer shaped piece of flint, is called by the Blackfeet I-nĭs´kĭm, the buffalo stone.

A small stone, which is often a fossil shell, or sometimes only a queer shaped piece of flint, is called by the Blackfeet I-nĭs´kĭm, the buffalo stone.