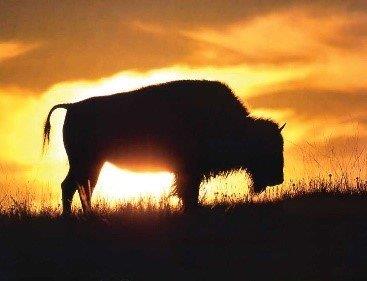

Bison at Camp Pendleton, US Marine Corp

The buffalo herd at Camp Pendleton in California.

By Blake Stilwell, USMC

Camp Pendleton first received its bison from the San Diego Zoo between 1973 and 1979. The earliest numbers were small, just 14 individuals.

The installation was a perfect home for the bison, and not just because there’s no better friend than the Marines. Camp Pendleton is enormous; with 125,000 acres of land and two natural water sources, there’s plenty of room on the range to roam.

Over time and with protection from the Marine Corps, the number of bison has grown so much, they sometimes interfere with basic training and base operations.

By 1987, the Marine Corps estimated the herd had grown to 50. In 1999, the number was 62. Today, it estimates there are 90 on the base.

The herd is managed by the Camp Pendleton Game Warden’s Office, which advises viewers to stay at least 150 feet away from the six-foot-tall, 2,000-pound gentle giants. While not as aggressive as predatory animals, bison are still defensive and can turn aggressive very quickly.

When threatened or repeatedly approached, bison will use that bulk to ward off potential attackers. Most injuries at the hands (hooves) of bison usually come because an onlooker got too close to the animal. It’s hard to blame a species that was almost hunted to extinction for being overly cautious.

Camp Pendleton says its game warden’s office is responsible for monitoring the bison population and keeping track of its genetic diversity, overall health and total population.

The Game Warden’s Office has a management plan that allows the bison to roam free while keeping them (as best they can) from interfering with Marine Corps training exercises.

Still, accidents happen. The Marine Corps estimates two bison from the herd die each year, either from car accidents or some other kind of mishap. That kind of success will likely ensure the Marine Corps bison are welcome on Camp Pendleton for the foreseeable future.

Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog