Part 2—Horses Return to Native Americans

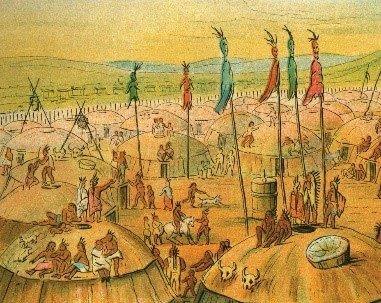

Horses were an invaluable addition to the lives of Plains Indians. The Lakota loved and honored their horses. Decorative painting on tipis and hides often depicted men on horseback. On this tipi, the lowest row of horses and riders appear to be racing. Above, the images seem to indicate scenes of warfare. Photo courtesy of State Historical Society ND 1952-5531.

Horses evolved in North America. They went through many stages, changing from small and three-toed to one-toed and increasing in size to about the size of a deer.

They were well-adapted to the grasslands of North America, but they disappeared from the continent around 10,000 years ago. Scientists do not know why horses disappeared. It may have been because of some ecological disaster, disease, over-hunting by humans—or all three.

Paleontologists have deterrmined that some North American horses migrated westward and crossed the Bering Land Bridge into Asia where they prospered. Whatever the cause, there were no horses (Equus species) in North America from about 10,000 years ago until about 1520 A.D.

When Columbus made his second expedition in 1493 to the Caribbean islands, he brought horses, but it is doubtful that any of those animals were released on the continent.

In 1519, however, the Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) brought horses into the southern Great Plains of the continental mainland. Horses returned to North America, but they were now domesticated animals trained to work for humans.

Spanish explorers, missionaries and rancheros kept horses for transportation, for beasts of burden and for farm work.

The early Spanish closely guarded their horses and did not allow American Indians to own them.

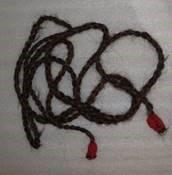

This intricately braided rope, or horse rein, was made from red (sorrel), black, and white horse hair. It was probably used only for ceremonial purposes. This rope is in the collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. SHSND Museum 10934.

Many tribal historians believe that American Indians only rarely captured and trained wild horses.

American Indians acquired horses in 1680, when Pueblo peoples, led by Popé, drove the Spanish from New Mexico and captured the horses left behind. Comanches, Utes and Apaches captured horses and developed the skills they needed to ride and hunt on horseback.

Trade between tribes brought horses north from New Mexico. The Shoshonis (who now live in Montana) began making journeys south to trade for horses.

Their trade involved more than horses. They also traded buffalo robes and other goods for bridles and saddles. Using the Spanish model, American Indians made their own bridles and saddles.

By 1700, a few horses had reached the tribes of the Upper Missouri River country. By 1750 horses were incorporated into the life ways of Indian tribes and were part of a web of trading and raiding among the tribes.

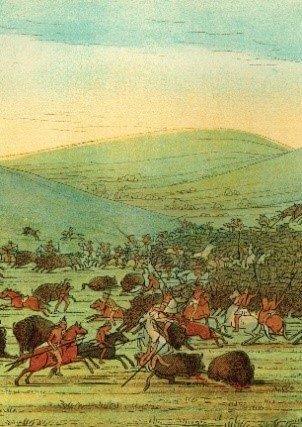

Horses brought great advantages to Indian tribes. With horses, hunters could travel long distances to find bison herds. Horses added speed and efficiency to the bison hunt. And they were useful in hauling heavier and larger burdens than a dog or human could.

However, horses required feed—grass or cottonwood tree bark for winter feed. And riders were occasionally injured by an accident with a horse.

Like metal goods and guns, horses arrived on the northern Great Plains in advance of non-Indian traders and explorers.

Though horses and other European trade goods brought many advantages, they were also a sign that white soldiers and settlers would soon follow.

Section 2: Lakota Horses

During the decades before 1650, Lakotas, a branch of the large Dakota (sometimes called Sioux) nation, lived in the woodlands east of the Red River.

During the 17th century, they moved into the Great Plains and occupied the land between the Red River of the North and the Missouri River.

They began to live a more nomadic life than they had in the woodlands. They followed bison herds and became expert hunters.

Man’s saddle. The saddle is made of two pieces of wood joined by a piece of elk horn in front (pommel) and in back (cantle). This style of saddle would have been used by a man. After 1800, the owner of the saddle might have added metal rings or other pieces he acquired in trade. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 1982.285.38.

According to the winter count of Battiste Good, the southern bands of Lakotas first saw horses around 1700. By 1715, horses appeared frequently in Good’s winter count.

Sometime in the middle 18th century (around 1750), Lakotas used horses regularly for hunting and transportation. Most likely they traded with other tribes for horses as they found out how useful horses could be.

Man’s saddle as viewed from the front. The entire saddle made of wood and elk horn was covered in “green,” un-tanned bison hide that was stitched with sinew and allowed to dry. The saddle was very strong and might have been used for generations. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 1982.285.38.

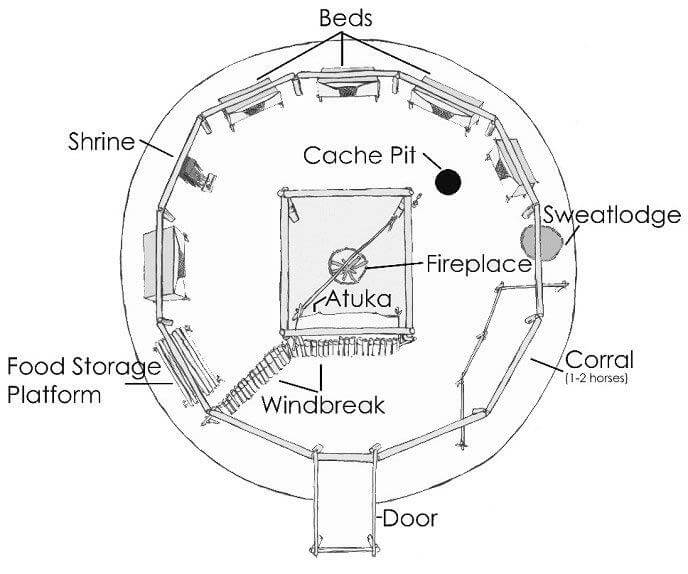

Horses became an important part of society because Lakotas were nomadic. They moved their villages to places where they had good grass and water for their horses and nearby bison herds.

Horses made moving the village much easier because they could carry heavy loads. Horses also made bison hunting more efficient because a horse could carry a hunter right into the bison herd.

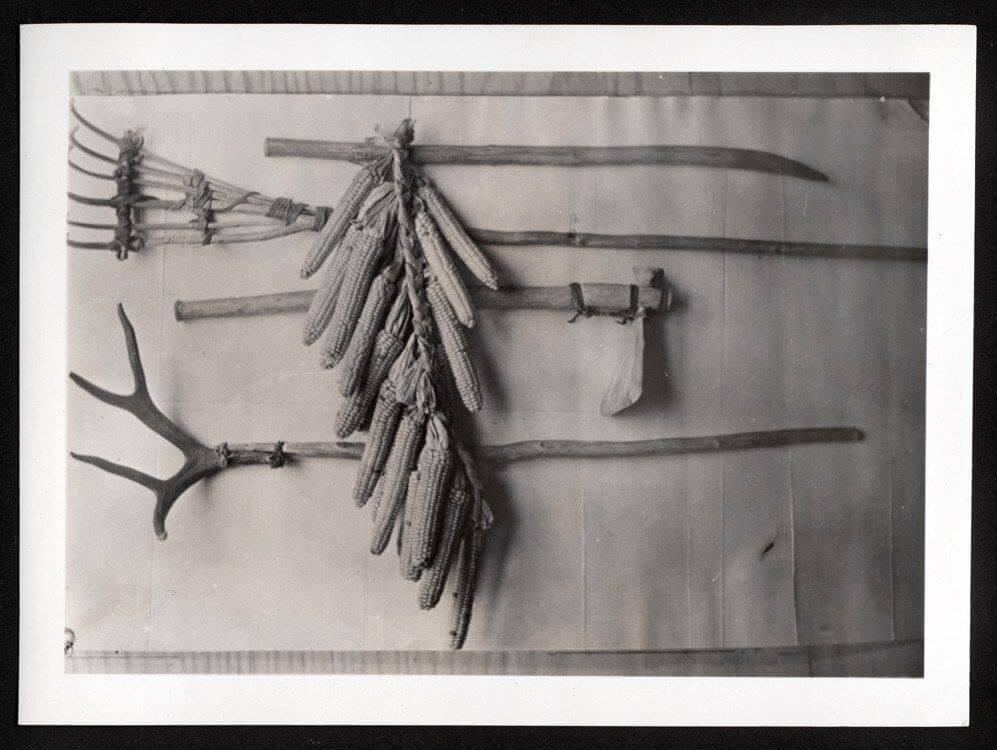

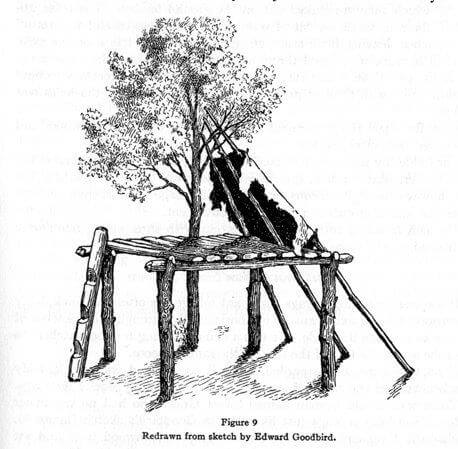

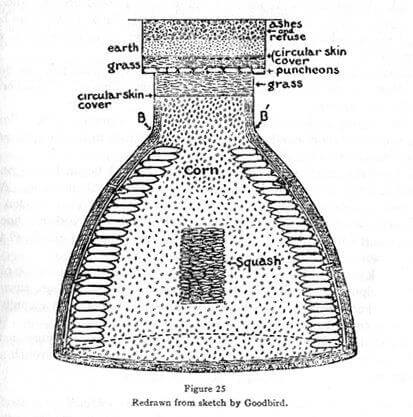

Older men and boys sometimes used saddles in the bison hunt. The saddle was made from two pieces of wood, about 20 inches long and one and one-half inches thick. The two pieces were joined by an elk antler that was shaped and fitted to form an arch just behind the horse’s withers.

Another piece of elk antler joined the two pieces of wood behind the rider.

Raw bison hide covered the entire saddle and was stitched into place with sinew. When the rawhide dried, the wood and antler saddle was very strong. The saddle was attached to the horse with a girth of bison leather.

Some hunters made stirrups of buffalo hide or wood. These well-made saddles might have been used by generations of Lakota hunters.

This woman’s saddle is similar to a man’s saddle, but the elk horn pieces in the front and the back rise higher than a man’s saddle. The higher pommel and cantle allowed a woman to carry bags of goods and even small children (safely secured to the saddle). SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 1991.41.2

This horse has a traditional saddle and halter. Saddle of wood, is joined with elk horn in the front (pommel) and back (cantle). The halter is made of rope or twisted rawhide, but it is fashioned in the traditional manner without a metal bit. The horse pulls a travois of tipi poles. A baby is carefully secured to the webbed “basket” between the poles. The horse’s colt stands behind her. SHSND 0739-v1-p52.

A Lakota family might own several horses, but a bison hunting horse was a special animal that was not used for other purposes, except perhaps war. When a man wanted a hunting horse, he selected a fast young horse and trained it to hunt bison.

He rode the horse alongside and into herds of running horses. In this way, the horse became trained for speed and learned how to approach a moving herd of animals. The hunter also rubbed bison robes over the horse so it would learn to know and not fear the smell of bison.

These stirrups of the traditional Indian saddle were made of wood covered with hide. Some stirrups were made from rawhide without wood. These stirrups were used with the men’s saddle above. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 1982.285.38

Rope. Horses brought many advantages to American Indians. Though Indians had made rope from the wooly hair of bison for centuries, rope-makers strengthened ropes by adding horse hair to the braided fibers. This braided rope is made of horse hair with a little wooly hair included. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 583.

Some hunters rode after the bison herd with only a halter on their horse. Others used a saddle as well.

When a Lakota horse was prepared for a bison hunt, it had a halter, or head piece, that was made of leather tanned from a bison hide. There were two leather straps: one strap encircled the horse’s muzzle just behind the corners of the mouth.

This strap was attached to another strap that passed behind the horse’s ears. Another long leather strap was attached to the halter and extended back to the rider. The halter fit somewhat tighter than modern halters.

Horses were highly valued by their owners. They often “dressed” their horses in beautifully decorated bridles and saddle bags. This saddle bag was to be carried across the horse’s back behind the saddle. Though there is a small opening in the saddle bag, this one was not designed for practical use. Evidence indicates that this saddle bag may have been owned by the great Lakota leader Sitting Bull. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 11711.

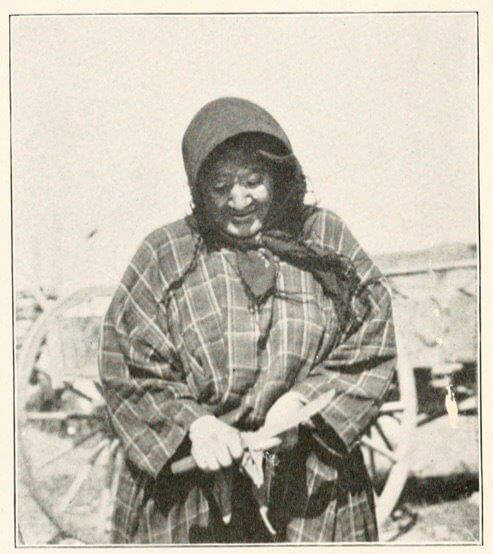

A woman’s saddle was made in a similar way, but constructed so that the woman could also carry large packs of household goods or children on horseback.

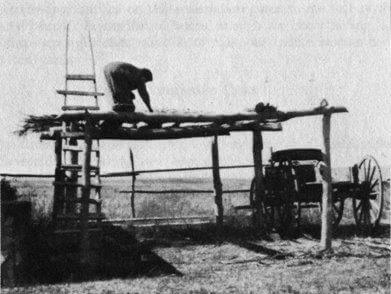

Some Lakota horses were used to pull loads packed onto a travois (TRAV-wah, or TRAV-voy). A travois was made using tipi poles that were inserted into a harness placed over the horse’s back.

Horse owners often decorated halters to demonstrate the high value of their horses. This bridle brow piece was decorated with dyed porcupine quills, metal tinkling cones, and tassels. SHSND collections. SHSND Museum 1882.

A webbed basket was suspended between the poles for carrying children, elders, or ill adults, household goods, or bison meat. Before horses came to the northern Great Plains, dogs pulled much smaller travois.

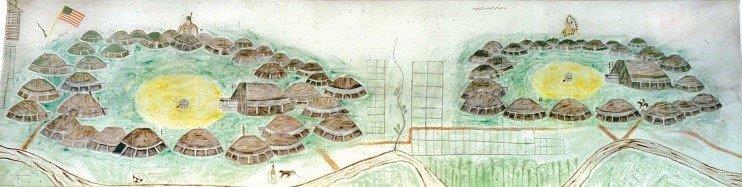

Before the Lakota and other tribes acquired horses, they used dogs to carry burdens. The dog travois is made in a way that is very similar to the horse travois, but it is much smaller and carried much lighter loads than horses. Among the Lakota, making and packing the travois was women’s work. SHSND 1952-6303-2.

A woman who could pack a travois efficiently and well was held in high esteem.

Horse hair had many uses, too. It could be removed from the mane or tail without hurting the horse and might be used to decorate a headpiece or clothing.

Horse hair was also added to bison hair in making very strong ropes. Lakota artists often used images of horses in painting or beadwork.

Lakotas loved and cherished their horses. For special occasions (religious ceremonies or war) a horse might be painted with symbols that were important to its owner.

Some people decorated their horse’s bridles, saddles and saddle bags with beads or quillwork.

One mask (in the Smithsonian Institution today) was made of bison hide. Holes were cut in the hide for the horse’s eyes and ears. The hide was decorated with feathers.

Horses came to represent wealth to the Lakotas. Both men and women could own horses.

Men might acquire them through trade or in raids. A woman might receive a horse as payment for her beadwork.

But, in the Lakota tradition, wealth was to be given away to honor someone else who had done a great deed, or to honor someone who had died. Horses often changed hands in giveaway ceremonies.

Historians debate the impact of horses on the Lakota way of life. Some historians argue that horses changed the Lakota way of life and even had an impact on their religious ideas. Other historians state that horses allowed Lakotas to improve, but not change, their way of life.

The Lakota economy—or way of making a living—did not change greatly when they acquired horses. Lakotas continued to hunt bison and incorporate the great animal into every aspect of their lives.

Because horses made bison hunting so much more efficient, they, too, came to be honored in many parts of Lakota life.

Once the bison were gone from the northern Great Plains, some horses remained with the tribe to connect the Lakota people to their pre-reservation past.

ND Studies, 8th Grade Lakota Horses.

______________________________________________________________________________

NEXT:

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog