Knife River Flint

Prized Knapping Stone of the Northern Plains

By Gene Gade

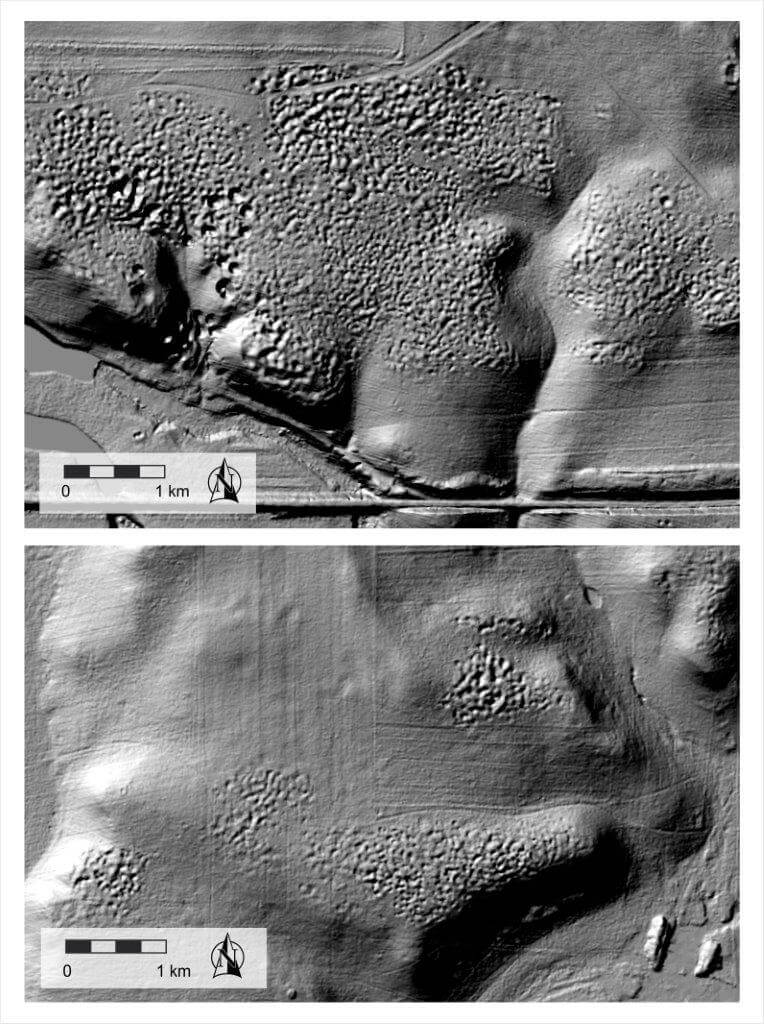

Aerial photo of Knife River Flint quarries shows pockmarked landscape where chunks of Knife River Flint were dug out of soil for at least 11,000 years.

No man’s land on a World War I battlefield? Impact craters on Mars or the Moon? An abandoned bombing range?

From the air, certain pastures near the Knife River in central North Dakota are as pockmarked as any of the above.

However, these pits are not the result of violence or astronomical cataclysms. They are really hundreds of small mines used by Native Americans to quarry a precious resource over a period of at least 11,000 years.

What resource? Native Americans were digging for nodules of a dark brown rock, variously described as caramel or root beer colored, and well known to archaeologists and geologists as Knife River Flint (KRF).

KRF was one of the most sought-after materials used to make tools and weapons and was traded over a vast area of the continent.

Chunks or nodules of Knife River Flint like this were found scattered through the quarries. They were dug out of the soil, fashioned into points and traded to visiting tribes for at least 11,000 years. Traded again and again, they became highly prized and have been found thousands of miles away.

Artifacts fashioned from KRF include Clovis points made more than 10,000 years ago and KRF implements have been found thousands of miles from the quarries . . . from Montana on the west, Alberta on the north, New Mexico on the south and New York state in the east.

Clearly, KRF was a valued commodity in a very large and ancient trade network.

Knife River Flint arrow point recovered from excavations at the Vore Buffalo Jump in Wyoming. The Flint traded from Knife River showed the characteristically root beer or caramel color with extremely hard, sharp edges.

What’s special about Knife River Flint?

Chemically, flint is a type of quartz. The primary compound in flint and related minerals is silicon dioxide a.k.a. silica, one of the most common compounds in the earth’s crust. Silica is slightly soluble, so it often dissolves in water, percolates through sedimentary rocks and precipitates where there are voids in the surrounding rock, forming hard nodules of various sizes.

Flint is usually formed within a chalky sediment. Like other forms of silica used to make tools, flint is hard . . . about 7 on a scale where 10 is hardest. It is also brittle and fractures into long, thin, cores. When struck by a skilled “knapper,” flint and its “lithic“ cousins in (chert, chalcedony, jasper, agate, etc.), form curved chips called “conchoidal fractures” and can have very sharp edges.

That’s why they make good arrow points and blades. Due to minute impurities, Flint and similar minerals usually have distinct colors and sometimes contain tiny fossils. Often flints are fairly dull and opaque, but some have a shiny luster and are translucent.

Knife River Flint has properties in spades that make it a very desirable tooling stone. Plus its distinctive and beautiful.

Where did the Flint come from?

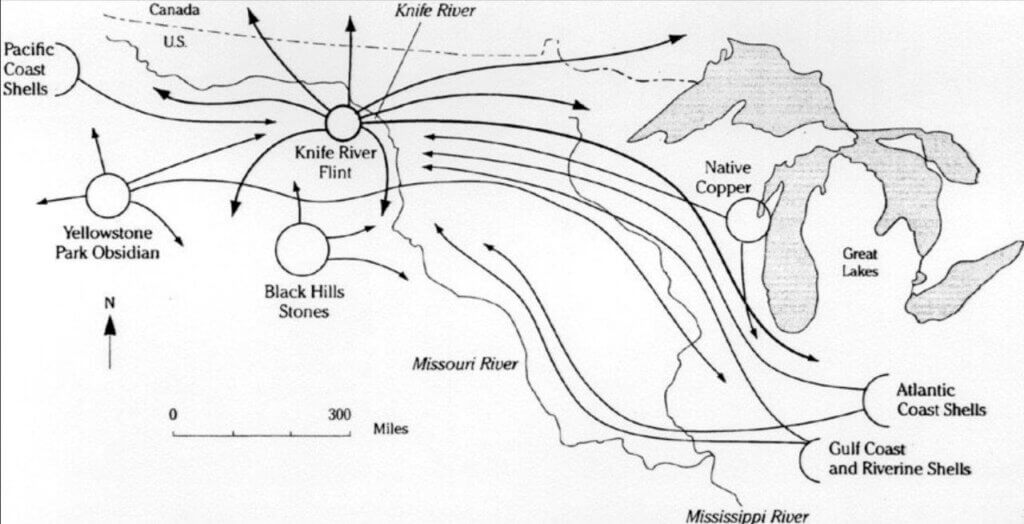

Knife River Flint from North Dakota as a trade commodity had wide distribution across the US and Canada. Library of Congress.

Nobody knows for certain where Knife River Flint was formed because the parent rock has not been identified with certainty. Most likely it was embedded in rock derived from a peat bog that existed about 50 million years ago. The strata in which it formed were probably part of the Killdeer Mountains.

The flint-bearing rock was apparently carried away by glacial ice or water and deposited in the gravel along what became the Knife River drainage.

Chunks of KRF with diameters of two feet have been found, but most nodules are much smaller. They are distributed in a relatively small stretch of the Knife River valley, but quarrying has been very intense in several small areas along the flood plain.

The largest quarry has been designated a National Historic Site. Another is in a National Wildlife Refuge.

Knife River Flint in the Trade Network

An impressive trade network linked many parts of North America hundreds of years before Europeans entered the continent and began trading for furs and other goods.

In what is now the Southwest US, pueblo Indians at Chaco Can[1]yon and other sites carried on extensive trade extending in several directions, especially to Mexico and Central America.

In the Northern Plains, Mandan and Hidatsa Indians were the great entrepreneurs. From their earthlodge villages along the Middle Missouri River, the Mandans and Hidatsas often traded part of their abundant corn, bean and squash products for buffalo meat and hides with the hunting tribes that surrounded them.

More than that, they became the middle men and importers where tribes throughout the region came to acquire goods that did not occur where they lived. The Mandan/Hidatsa trade network extended well beyond North Dakota.

Mollusk shells from the Pacific Northwest, Gulf of Mexico and even the Atlantic Coast are found in excavations of Mandan villages Tribes along the Great Lakes were beginning to mine and smelt copper which also became a trade item.

What durable resource of their own did the Mandan and Hidatsa have to trade? Knife River Flint!

What’s This got to do with the Vore Buffalo Jump?

Not surprisingly, Knife River Flint is found among the bones at the Vore Site. About 7 per cent of the artifacts at the VBJ are made from KRF.

This point demonstrates the sharp edges and translucent properties of Knife River Flint. The brown flecks in the stone are fragments of tiny fossils.

While other types of stone from less distant quarries are dominant, the presence of KRF raises intriguing questions for archaeologists. KRF is so distinctive and the area where it was mined is so restricted, there is no question of where it originated. However, it is not certain who brought it to the Vore site.

A 10,000+ year old Clovis Point made from Knife River Flint that was found in southern Iowa.

Pairing modern tribes with prehistoric stone tools is not exact science. At best, its inferential /circumstantial “evidence.” Having acknowledged that, what inferences can be made about KRF and the VBJ?

Start with what’s known. The Hidatsa lived in large villages at the confluence of the Missouri and Knife Rivers and probably the dominant tribe along the latter during the period of Vore Site use. They are almost certainly among the tribes that quarried and /or traded the famous flint.

In the late-1500’s the Hidatsa had a major family feud. The schism was significant enough that some portions of the tribe moved away from the central farming area along the Missouri and shifted their economy toward nomadic buffalo hunting.

As they adapted to the mobile life on the Plains, the breakaway group developed its distinctive identity. They maintained a trade relationship with their farming cousins, but they continued to adapt to the tipi-dwelling hunting culture. They referred to themselves as “the people of the long-beaked bird,” possibly referring to cranes as a spiritual totem.

However, other tribes, referred to them (perhaps in a derogatory way) by the name of another bird species. They became known as Crows and that name is still applied to them.

It’s known from oral history, supplemented by archaeology, that the Crows migrated toward the Black Hills and that they were dominant in the region during much of the 1600’s. The artifacts of Knife River Flint that are found at the Vore Site are mostly from that century.

From archaeological sites such as one along the base of the Bighorn Mountains, the Crows are known to have conducted communal buffalo jumps. If they did buffalo jumps where the Plains meet the Black Hills, they may very well have used the Vore Site.

So, the inference is that the ancestors of the Crows may well have brought Knife River Flint to use at the VBJ. Additional research is needed to test such inferences and there’s no better place to do the archaeological component than at the Vore Buffalo Jump.

Guest Article by Gene Gade. As the County Extension Agent in Sundance Wyoming, Gene Gade served 20 years as president of the non-profit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation, helping to develop and guide the research, education and economic potentials of the Vore site until his retirement to Oregon, where he continued to write for the VBJF Newsletter. Reprinted from the VBJF Newsletter with permission: Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation, 369 Old US 14, Sundance WY 82729; Tel: (307) 266-9530, email: <info@vorebuffalojump.org>

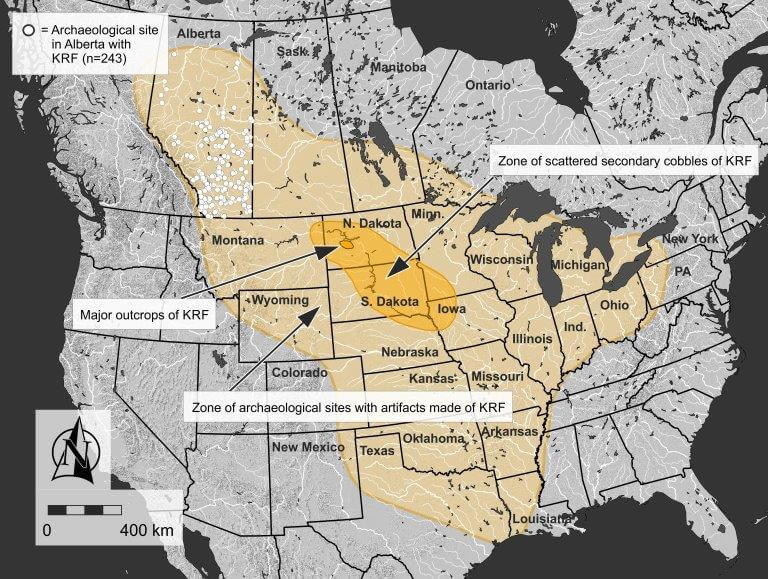

Artifacts made from KRF have been found thousands of miles from the North Dakota quarries in every direction. Clearly, it was highly valued as a trade item over 10,000 years ago.

Most likely the nodules were embedded in rock derived from a peat bog that existed about 50 million years ago. Archeologists suggest the strata in which it formed may have been part of the Killdeer Mountains.

Knife River Flint as a trade commodity—(Library of Congress)

Knife River Flint Artifacts Found in Alberta

Map shows distribution of 243 Knife River Flint artifacts found in Alberta (white dots) and widely across the US and Canada (tan color). Gold color circle shows major outcrops of KRF in western North Dakota and somewhat larger zone of scattered secondary cobbles. Source: Todd Kristensen, ND.

Anthropologists in Alberta Canada have documented 243 Knife River Flint artifacts found throughout the province, as reported by Emily Moffat, Regulatory Approvals Coordinator, Archaeological Survey of Alberta, Canada.

Over the course of the past 13,000 years, Knife River Flint was shaped into projectile points, tools and some unusual eccentric forms.

Moffat notes that this was a time of limited human mobility—with only dog travois to carry their goods in travelling—compared with modern times.

Yet Knife River Flint items were regularly transported hundreds of miles from their source in North Dakota, where it was quarried for all those thousands of years. All of it originated in a relatively small region which contains the majority of quarry pits.

The qualities in the Knife River artifacts that made them so desirable to primitive people were no doubt their ability to flake predictably and stay sharp.

However, in addition, some speculate that bison-hunting peoples of the past may have attributed spiritual properties to these rocks of beauty which often have translucent colors described as root beer or coffee. Often tiny fossils are visible within.

Knife River Flint (KRF) was apparently considered significantly more valuable than other flint materials, so great efforts were invested in procuring it, Moffat says.

Dunn and Mercer Counties of North Dakota were the most intensively quarried regions, and evidence of those activities is still found on the landscape today. Pre-contact quarry pits appear as pock marks on LiDAR imagery, a remote sensing technique that removes surface vegetation.

The primary source area is about 200 hectares and contains 29 pit complexes, each with up to 75 individual pits per hectare. On average these pits are 6 metres in diameter and 1 metre deep, with the largest reaching 20 metres in diameter and 2 metres deep.

The pits visible on imagery represent the most recent quarrying activities but many were excavated two or three times prior, illustrating the high demand for KRF.

Dunn and Mercer Counties of North Dakota were the most intensively quarried regions. Pre-contact quarry pits appear as pock marks on LiDAR imagery, a remote sensing technique that removes surface vegetation. Source: Todd Kristensen with LiDAR data provided by the North Dakota Geological Survey, 2017.

Moffat notes that KRF was first formed when low-grade coal, or lignite, was turned to stone by silica (or quartz) mineralization. These original rock formations, thought to be about 50 to 30 million years old, were eroded by glaciers and water, resulting in secondary deposits of loose pebbles and cobbles.

KRF could therefore be pried from the ground quite easily as opposed to chipped from a rock face or collected as river cobbles like some other lithic materials. Tools typical to the period, such as fire-hardened digging sticks and bison scapula hoes and shovels, would have been used to unearth KRF.

There are difficulties identifying which artifacts are indeed KRF. Moffat says there is an abundance of similar materials in North America made from other silica-rich rocks such as chert, chalcedony and petrified wood which can resemble KRF. Larger pieces of KRF may even have plant fossils embedded within it, similar to petrified wood. The geochemistry of KRF is quite variable.

Ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence can be used to tell some rock types apart. KRF was once thought to fluoresce a specific color, which helped archaeologists identify it, but recent work suggests that it fluoresces a range of colors under longwave UV light—from yellow-gray to orange, with some specimens of KRF that do not fluoresce at all.

The chain of interactions that transported KRF to Alberta and other far-reaching regions thousands of years ago is remarkable, according to Moffatt. KRF cobbles, cores and tools were passed between countless hands to get from the quarries to the people who used the stone on a daily basis.

The presence of KRF and any other exotic material at archaeological sites therefore signals a rich history of human connection and an incredible journey across cultural landscapes of the past.

For more information:

Ahler, S.A. 1986. Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations at Site 32DU508. State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck, North Dakota.

Clayton, L., W.B. Bickley, Jr., and W.J. Stone. 1970. Knife River Flint. Plains Anthropologist 15:282-290.

Clark, F. 1984. Knife River Flint and interregional exchange. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 9:173-198.

Dawe, R.J. 2013. A review of the Cody Complex in Alberta. In: Paleoindian Lifeways of the Cody Complex, edited by M.P. Muñiz and E.J. Knell, pp. 144-187. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Evilsizer, L.J. 2016. Knife River Flint Distribution and Identification in Montana. M.A. thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana.

Gregg, M.L. 1987. Knife River Flint in the northeastern Plains. Plains Anthropologist 32:367-377.

Hickey, L.J. 1977. Stratigraphy and Paleobotany and of the Golden Valley Formation (Early Tertiary) of Western North Dakota. Geological Society of America Memoirs 150, Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado.

Kirchmeir, P.F.R. 2011. A Knife River Flint Identification Model and its Application to Three Alberta Ecozone Archaeological Assemblages. M.A. thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Kristensen, T., E. Moffat, M. J. M. Duke, A. J. Locock, C. Sharphead, and J. W. Ives. 2018. Identifying Knife River Flint in Alberta: A Silicified Lignite Toolstone from North Dakota. Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper 38:1-24.

Root, M.J. 1992. The Knife River Flint Quarries: The Organization of Stone Tool Production. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington.

Root, M.J. 1997. Production for exchange at the Knife River Flint quarries, North Dakota. Lithic Technology 22:33-50.

Steuber, K.I. 2018. Geochemical Characterization of Brown Chalcedony during the Besant/Sonota Period. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

VanNest, J. 1985. Patination of Knife River Flint artifacts. Plains Anthropologist 30:325-339.

Written by Emily Moffat, Regulatory Approvals Coordinator, Archaeological Survey of Alberta, Canada.

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog