The Vore Buffalo Jump—Part 1

Photo courtesy Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation.

Vore Buffalo Jump in northeastern Wyoming does not involve a cliff at all, but rather, a trap.

It developed when a sinkhole opened up at the western edge of the Black Hills cave system and was used as a jump to trap bison by Native American hunters for about 250 years.

When the hole was first used some 450 years ago, it was 75 feet deep and narrower than now. Today, it is about 50 feet deep and more than 200 feet across.

The buffalo bones are in 22 layers laid down one by one and are regarded by archeologists as the remains of 22 separate hunts that happened from 1559 to about 1800. An average of fewer than one hunt every 10 years. All except two were fall hunts as determined by tooth age of calf skulls found.

By the time homesteaders began to claim land in the area, there was no evidence on the surface of the sinkhole floor that this site had been used as a bison trap. As it did after each hunt, the sinkhole had blown in with silt and grassed over.

Named for the Vore ranching family who donated the land, the jump itself is a large natural sinkhole at the base of a long sloping ravine that opens out into a broad, flat valley.

It is located only 5 miles west of the South Dakota line, not far from Spearfish, SD or Devil’s Tower in northeast Wyoming and directly in the path of Interstate-90, which crosses the nation from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

An Era of Dramatic Change

The last jump at the Vore site happened sometime between 1770 and 1800. The technique was being made obsolete by the advent of horses and guns.

One of the rare and interesting things about the Vore site is that it lasted only 250 years as a buffalo jump—from 1550 to 1800.

Those were years of dramatic change for Native Americans who lived on the plains. The changes clearly played out and revealed themselves in the research coming from Vore Buffalo

The first walking trail follows the slope in gradual descent into the sinkhole at the bottom. In building below is where the original research began and continues, layer by layer. With permission, courtesy VBJ Foundation.

One of the rare and interesting things about the Vore site is that it lasted only 250 years as a buffalo jump—from 1550 to 1800.

Those were years of dramatic change for Native Americans who lived on the plains. The changes clearly played out and revealed themselves in the research coming from Vore Buffalo Jump.

Before they had horses Native Americans depended on dogs for transporting their goods. Courtesy VBJF.

The era began before the time of horses on the Plains when humans depended on dogs for transportation of their goods. Gradually there came an acceptance of European trade goods such as metal knives and guns that began reaching remote corners of the west.

Then came the flowering of an amazing horse culture that brought Native Americans great freedom of movement and established them as some of the greatest horseback riders the world has ever known.

At the same time, many tribes began moving west where they took up a nomadic lifestyle following herds of buffalo and developing a culture dependent and spiritually interrelated with them.

Thus the Vore jump tells us a great deal about who these people were, where they came from, and how they lived during that time of transition. It is being revealed by cuts in the bones and other evidence found there.

Colorful badlands formations and higher altitude pine-covered hills and rocky ridges enhance the exotic scenery surrounding the Black Hills to the west into Wyoming. Courtesy VBJF.

How the Sinkhole was Used

Buffalo or bison ranged from what is now Canada to Texas when the Vore Site was first used, according to the Vore manual for guides.

At that time the Native Americans way of life on the Great Plains depended on bison. Before Europeans brought the horse to the Americas, they were hunted on foot, a few at a time, or communally by driving the animals into pounds (essentially corrals) or off precipices.

At the Vore Site, the sinkhole was the trap, and bison butchering took place down in the 60-foot hole. The bones of the bison and the stone tools left by the hunters are found in the layers of sediment that make up the sinkhole floor.

“Archaeologists estimate that around 200 people would have come together for a big jump. They would have belonged to one tribe, but the Vore Site was used by a number of different tribes over a period of about 250 years,” says the manual.

“Just to the west of the site would have been good pastures, and about three and a half miles to the east were good camping sites, water and wood, along Sand Creek near what is now the town of Beulah.”

These may have been places where a tribe camped for the longer time needed to dry out the buffalo hides and make jerky and pemmican after a successful hunt.

“In the fall (after the breeding season) bulls would have wandered off and cows and calves split into small herds of 40 to 60 head.

“Late October and early November a tribe would plan a hunt. Runners would go to the far side of a small herd and worry the bison, which caused the smaller herds to gather. The bison thought there was safety in numbers. The large herd, of some 500 or more, would be worked slowly toward the trap.

“There are remnants of drivelines formed by rock cairns (similar to our replicas to the west of the sinkhole) in the pastures southwest of the site that point toward the sinkhole. The lay of the land around this sinkhole made it possible for the hunters to use it as a trap.”

Before the interstate highway changed the area, a draw provided a natural funnel leading into the sinkhole.

Hunters were stationed up along the sides and when the herd was a short distance from the sinkhole, they started a stampede.

If the bison herd was strung out running down the draw, many might have dodged around the trap down below when they came to it.

But with the full mass of bison stampeding and threatened by the sharp horns of those behind, they’d be down in the draw with the hole in front of them before they knew what was happening.

Bringing them narrowly into the hole tested the skill and bravery of hunters who clearly understood buffalo behavior. They had to keep the stampeding herd headed directly into the opening and not allow them to escape to the side. If even a few escaped, likely others would follow.

Then it was easy. Hunters gathered at the rim, shooting with lances or bows and arrows the buffalo down below not killed by the fall.

The sinkhole floor was a place of butchering. A trap with no escape.

The sinkhole was a trap with no escape, but could be dangerous with plunging, dying buffalo. VBJF.

Yet it must have been a dangerous place for hunters who entered the pit filled with dead and injured buffalo.

Then the meat had to be carried up and out or pulled up with hide ropes.

“These hunts happened before the local Native American tribes had horses. The bison had to be cut into pieces small enough to be pulled up and out of the sinkhole.

“Most likely men did the butchering. The women probably began work in camp right away, tanning hides and stripping and drying the meat. Meat and hides and large bones would have been transported on backs and via dog travois.”

Discovery of Vore Sinkhole

The Vore Buffalo Jump was discovered in 1969 by the Wyoming Highway Department while planning Interstate-90 Highway, according to Ted Vore.

Right-of-way purchased from the Vore Ranch encroached approximately 30 ft. over the edge of the sinkhole.

Highway engineers were concerned about gypsum sinkholes that might affect the stability of the highway and asked permission to build a road down into the sinkhole and drill.

Woodrow Vore, Ted’s father, suggested they drill up where the road was to be as gypsum sinks could be anywhere.

They trespassed anyway, bulldozed a crude road into the sinkhole, and sent a truck with an auger to check out its floor.

Wherever they punched a hole, they encountered buffalo bones within a few feet of the surface. Clearly this was an archaeological site, but the construction leaders would have preferred to keep quiet about the discovery and continue building the highway as planned.

Wherever they punched a hole the engineers brought up buffalo bones close to the surface. Cross trenches were dug to a variety of depths and investigated. VBJF.

However, an engineer on the crew blew the whistle and contacted George Frison, who at that time was a professor at the University of Wyoming, later to become Wyoming State Archaeologist, reportedly bringing with him a box of buffalo bones from the site.

Frison went to the Wyoming Department of Transportation and convinced them the site must be investigated. The story told is that Frison dumped the box of bones on the DOT director’s desk.

As he hoped, the decision was made to move I-90 a few hundred feet south and do an archaeological survey of the sinkhole.

Frison received permission from the Vores to excavate the bottom of the sinkhole to find the extent of the bone bed. During the summers of 1971 and 1972, excavations by Frison, his staff and students discovered that the bone bed covered the entire floor of the sink hole.

These first archaeologists also dug a shaft that went down about 25 feet. They discovered 22 layers of bones—each the remains of a single jump.

The Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation was locally formed as a vehicle to help the University in site development.

Unfortunately, you can no longer see the bones they dug up. When they left in 1972 they back-filled the trenches and shaft to protect the remaining artifacts. As they left, the team took about 4 tons of bones and many stone tools with them to the U of Wyoming to study.

In the fall of 1989, the Vores deeded the site to the University to be developed as strictly an education and research facility. The University was given 12 years to develop the site and open it to the public.

In the 12 years the University conducted studies and used the site for archaeology field school activities. However, they made no progress toward opening the site to public viewing. The excavation was covered up and nothing more was done.

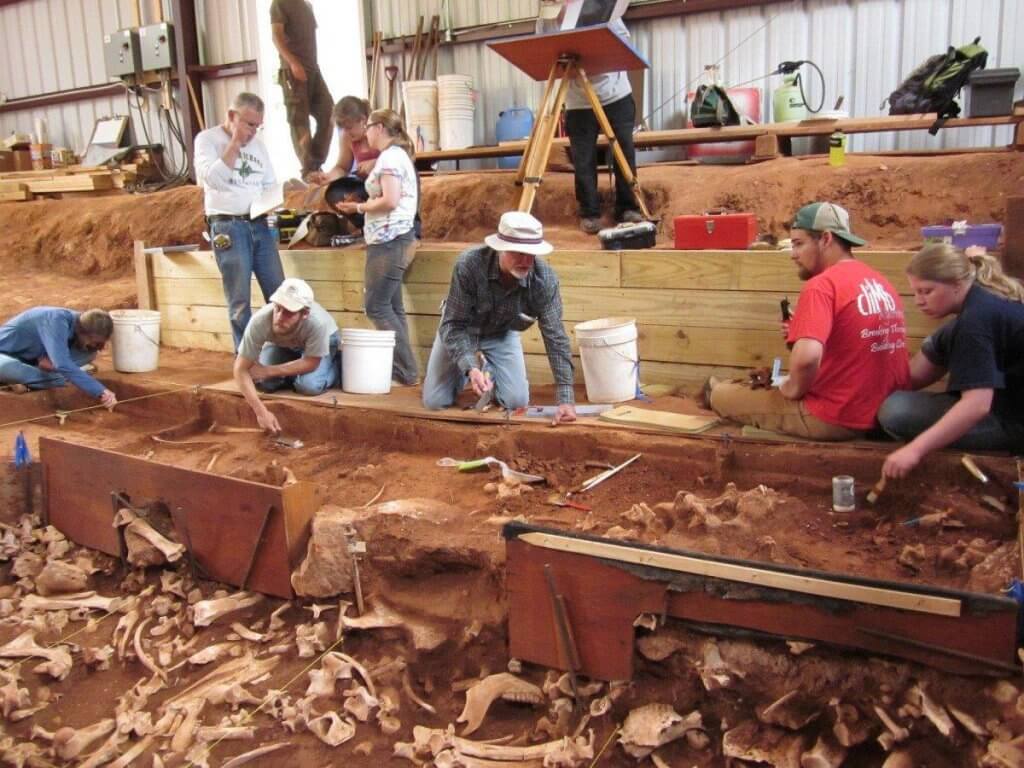

Working the bones. Excavation work resumed in 1995. Crew includes archaeologists, students and volunteers. VBJF.

Since the University did not meet the deed restriction of 12 years, the site was deeded back to the Vore Ranch and immediately deeded to the Foundation.

Excavation work began again at the Vore Jump site in 1995. The bones seen in open excavation units are from hunts that occurred from the mid to late 1700s—in other words, the most recently butchered.

The first hunt at Vore was in 1559, according to the experts. It is still deeply underground.

What caused the Sinkhole?

“To understand Black Hills geology generally and the Vore site sinkhole specifically, one needs to understand some properties of gypsum and limestone,” write Megan Schnorenberg and Gene Gade in their article ‘Geology of the Vore Buffalo Jump.’

We do not know when the Vore Site sinkhole formed but it was presumably hundreds of years before it was first used as a bison trap. Sinkholes result from the collapse of the roof of a cave formed in the underlying rocks.

Throughout the Black Hills rocks such as limestone or gypsum are dissolved by ground water to form caves. Both these types of rock are visible here at the Vore.

Sinkholes may be dry, as is the case at the Vore Site, or filled with water as observed a few miles to the east in South Dakota at the McNenney Fish Hatchery at Mirror Lake.

At Hot Springs, in the southern Black Hills, a sinkhole in the Spearfish Formation was the spectacular death scene for over 60 mammoths and is now the Mammoth Site and Museum, a popular tourist destination.

The formation of the sinkhole is related and similar to the caves that are interconnected throughout the Black Hills. Some have water and springs; some are dry.

Gypsum and limestone have in common the fact that both contain positively charged calcium ions. They differ in that the predominate negative ion in gypsum is sulfate (SO4) while the negative ion in limestone is carbonate (CO3). Both gypsum and limestone are somewhat soluble in water, but water can only hold a certain amount of either of them in solution. Gypsum is more soluble than limestone so gypsum usually dissolves first when they are in water together, according to the authors.

The opposite is true when they settle out of the water solution or ‘precipitate’ back into a solid—i.e. lime will precipitate before gypsum. Both are less soluble than some other compounds that are commonly dissolved in water, such as table salt (sodium chloride or NaCl).

When a body of water that contains all three compounds starts to evaporate (as in a shallow sea, desert lake or swamp), lime will precipitate into a solid first, then gypsum and, finally, salt.

If water returns the system later, they’ll generally dissolve in the opposite order . . . salt first, then gypsum, then limestone.

In the Black Hills, the Madison Formation formed from shells and dissolved calcium carbonate precipitated out of an ancient shallow sea, forming limestone. However, within the limestone, were lenses of gypsum.

Over time, cracks formed in the limestone and gypsum layer. Groundwater filled the cracks. The gypsum dissolved away leaving cavities in the limestone.

Additional water, combined with organic acids the water picked up as it soaked into the ground and percolated into fissures in the rock, dissolved some of the limestone.

The result is some of the largest caves in the world. Wind Cave in the Black Hills is not only one of the longest cave systems in the world—140 miles explored, the sixth longest cave—and is also the most dense (passages per mile) in the world.

Wind Cave has 95% of the world’s discovered boxwork rock formations, which are thin blades of calcite that project from the cave walls or ceilings. It is a sacred site for the Lakota people, as creation stories say this is where their people emerged from the earth, according to the Black Hills Visitor.

Jewel Cave has 132 miles surveyed and is also one of the world’s longest.

“About 60 million years ago, igneous (molten) rock pushed up and formed the bulge that ultimately became the Black Hills. During this uplift, the overlying sedimentary rocks (limestones, sandstones, shales, etc.) were tilted up.

“Eventually most of these overlying sedimentary rocks eroded away from the highest points in the Hills, leaving the granite core exposed in places like Terry and Harney Peaks.

“Erosion exposed the no-longer horizontal sedimentary layers around its flanks. These exposed sedimentary rocks on the so-called ‘limestone plateau’ are now the primary ‘recharge areas’ where water enters formations like the Pahasapa-Madison and Minnelusa Limestone formations.

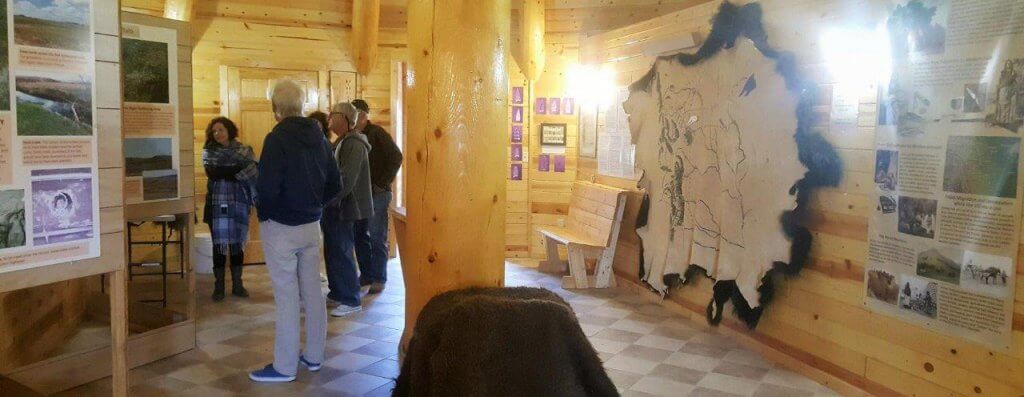

Each building houses exhibits on the hunters who used the site, how they jumped the buffalo and used the meat and hides. And the dogs that traveled with them. VBJF.

“Once in the rocks, the water flows downhill through fissures creating considerable gravitational pressure on this groundwater at lower elevations around the base of the Black Hills.

“Due to pressure, water from underground aquifers will flow upward into overlying strata if it can. If the water reaches the surface, the water will form a spring or artesian well, thus relieving the pressure.

“Major springs such as those that create Sand Creek (a perennial stream 3 miles east of Vore Jump) are an example. However, if, on its path to the surface, the pressurized groundwater passes through rock that is particularly soluble, a cave may form.

“That is exactly what the current theory suggests in the Vore Buffalo Jump sinkhole. U.S. Geological Survey geologist, Dr. Jack B. Epstein, who has been studying the Spearfish Formation sinkholes believes that the Vore Buffalo Jump sinkhole did not result from a collapse directly into a large cave in the underlying limestone.”

Rather, says Epstein, pressurized water in the tilted limestones rose through fissures until it reached the soluble gypsum at the base of the Spearfish formation.

“The gypsum dissolved, creating a solution cavern near the surface. The overlying ‘red bed’ sediments then collapsed at points into the void where the gypsum used to be, creating the Vore site sinkhole and others (such as the one just north and west of it).

“If the bottom of the new sinkhole is above the ‘potentiometric surface,’ (the level to which water in an aquifer would rise due to the natural pressure in the rocks), then the sinkhole is dry, if not, the sinkhole will contain a spring.”

“The sinkhole which is the focus of the Vore Buffalo Jump is surrounded by several gypsum beds, each 8-10 feet thick.

“Although no gypsum is present in the current bottom of the sinkhole, gypsum veinlets can be seen in the walls of the sinkhole, and are probably a result of the expansion of the gypsum and fracturing of the surrounding rock.

“The layers of bone which are found to extend 20 feet below what is now the natural bottom of the sinkhole indicate that sediment was rapidly deposited over the 300-year use of the sinkhole,” Gade and Schnorenberg report.

The Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation

All buildings and development of the site today has come through the efforts of the VBJ Foundation.

Three buildings currently make up the Vore Site. A small cabin serves as a place to greet visitors. The tipi on the sinkhole rim houses exhibits and restrooms.

The building on the sinkhole floor covers open excavation units where the work continues. Each building houses exhibits on the hunters who used the site, how they jumped the buffalo and used the meat and hides and the dogs that traveled with them.

Visitors see bones, not fossils. The floor is a work in progress, ongoing active excavations. VBJF.

What visitors see are bones, not fossils. This is not a museum exhibit but an active excavation. The bones in the unit on the southwest corner are from the very last hunt at the Vore Site and are about 250 years old.

This is essentially the garbage left behind after the butchering was completed.

“The Vore Site is managed by the 501(c)(3) non-profit Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation (VBJF) board. All board members are volunteers,” according to their website www.VoreBuffaloJump.org

“We have virtually no administrative costs. The admission charged visitors during the summer season pays the salaries of the interpretive staff. The buildings and exhibits have been funded through grants and donations.

“The VBJF took out a loan in 2013 to put up the tipi and drill a well, which allowed us to put in restrooms.

The Vore Site is open to visitors in summer (June 1-Labor Day) and off-season to school field trips by appointment. VBJF.

“The Vore Site is open to visitors from June 1 through Labor Day (8 am to 6 pm). The off-season field trip program hosts about 1000 students each year.”

(Based on information from the Vore Buffalo Jump website www.VoreBuffaloJump.org, the VBJF Interpreters manual and articles by Gene Gade. With permission from Gade and the Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation.

NEXT: THE VORE BUFFALO JUMP—PART 2

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog