BSC Bison Symposium, June 22-25, 2022, Part 2

On Friday afternoon, June 24, 2022, the two buses on tour for the BSC Dakota Bison Symposium continued by visiting the Johnson buffalo herd. Jim Strand—manager and herdsman—circles the herd with his feed wagon and the buffalo come running. Photo Credit Kathy Berg Walsh.

BSC Buffalo Symposium visitors stay on the buses and the buffalo mill around closely. This has always been a favorite sight for our visitors on tours. The yellow circles in the grass are buffalo wallows where bulls and others try to rub off their winter hair, pesky insects and can also be a mating challenge. Photo KBW.

Here you see the attentive mothers and some of the many young cinnamon-colored calves. When they are about 3 months old they begin to grow a hump and nubbins of horns and turn dark like their moms. Photo KBW.

Jim Strand steps onto the buses to explain how he handles his buffalo herd, answers questions and walks among the buffalo pointing out some of his favorite individuals as the buffalo continue to mill around. The rest of us stay on the buses, enjoying watching these magnificent animals close up, shooting photos and videos through the large bus windows. Photo KBW.

For the “Last Great” hunt here at Hiddenwood, 2,000 men, women and children traveled here from Ft. Yates on about June 20, 1882. Quietly the hunters rode up HIddenwood Creek (from the far left) spread out onto the hills on all sides, where as Agent James McLaughlin’s wrote, “50,000 buffalo” were grazing. They killed 2,000 buffalo the first day. The 2nd day they quick-butchered and cared for the meat and on the 3rd day they hunted again since the buffalo had not moved far, killing 3,000 more.

Then they camped for a time to dry and preserve the meat. Everyone knew their tasks: the men cut apart the large bones and hauled the meat into camp, while women cut it into thin sheets and hung them on willow branch frames and stretched and pegged hides to the ground to dry in the sun. Photo KBW.

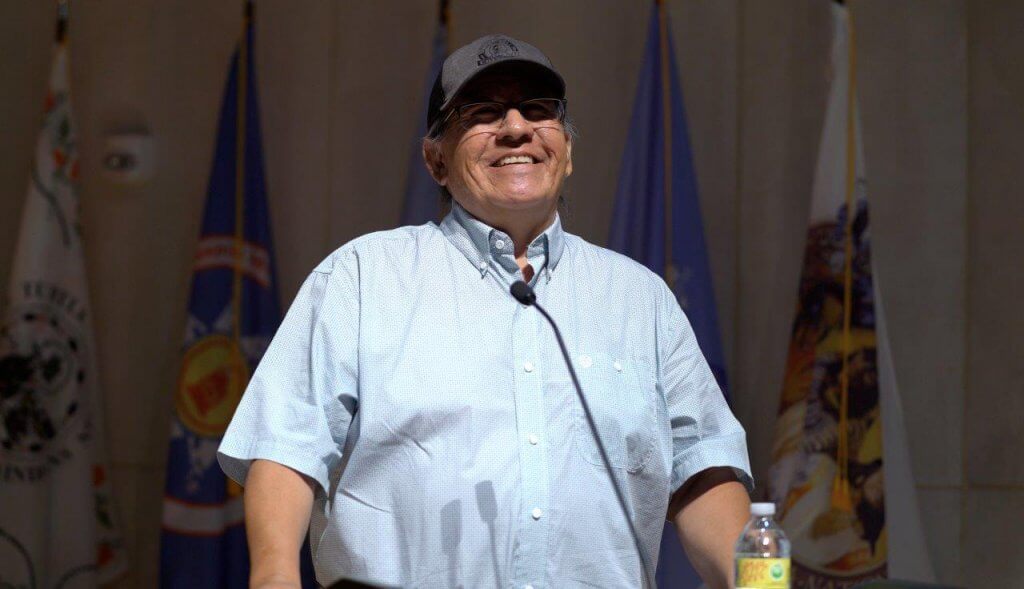

Dakota Goodhouse of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe gives his perceptions at Hiddenwood Historic Site on US Highway 12, halfway between Hettinger and Lemmon SD. A PhD candidate at NDSU in History and Native American Studies at United Tribes Technical College, he was one of the Native American storytellers on the bus from Bismarck. Photo credit James Kambeitz.

Young people enjoy the authentic tipi set up at the Hiddenwood Historic Site on the highway—also known as the Yellowstone Trail in this area. This tipi framework represents the many stone circles that filled this broad valley when first settlers arrived and the thousands of years before that when various Plains tribes came to hunt buffalo here and camped near the cliff which they called Hiddenwood. So named because it could not be seen until just before they came over the nearest hills. (The canvas tipi coverings made and set up by skilled Lakota craftsmen have been vandalized twice, so instead the poles are now anchored in place to suggest the proper tipi framework.) Photo KBW.

Once called the Butchering Site because of the abundance of buffalo skulls and bones found here when settlers arrived—we now call this the “Sitting Bull Hunt Site.”

Sitting Bull and his band came from their agency west of Mobridge—either to this place or within a few miles and killed the very last great herds of buffalo—about 1,200—on October 12 and 13, 1883. This was the Last Stand of the great herds of wild Buffalo.

William Hornaday, head taxidermist at the Smithsonian Museum, who wrote “The Extermination of the American Bison” in 1887 and predicted the buffalo would soon be extinct wrote “There was not a hoof left!” His book was published in 1889 by the US Government Printing Office.

The BSC visitors were encouraged to visualize significant events that took place here in this “most beautiful valley in our area,” where the land which looks much as it did 150 years ago:

In the centuries before they owned horses and guns, ancient Native Americans hunted here with homemade weapons and cared for their meat. Women dried buffalo meat on willow racks and stretched their hides.

in 1823 Major Henry came up the North Grand River with his fur trading party, although one of his tough mountain men, Hugh Glass, was severely injured by a grizzly bear and left to die near Shadehill without his weapons.

General Custer rode through here with 1,200 men of the 7th cavalry, 200 covered wagons pulled by 6 mules each, a medical team, gold miners, reporters of leading newspapers, Native American scouts, his 7th Cavalry band—in the mornings dispatched to play military airs including Custer’s favorite (“The Girl I left Behind”) from a nearby butte as the Calvary rode by with flags flying. In addition, 300 head of beef cattle were driven along by cowboys to be butchered and fed as needed to the two thousand men on the expedition to the Black Hills in 1874.

And finally in this place we can imagine “Ghost riders in the Sky.” Texas cowboys trailed great herds of longhorn steers, a thousand at a time, from over the far horizon. The steers fattened and grew larger as they grazed our high-protein grasses. Some said so did horses and even the cowboys when they came up north! Photo Credit Kendra Rosencrans.

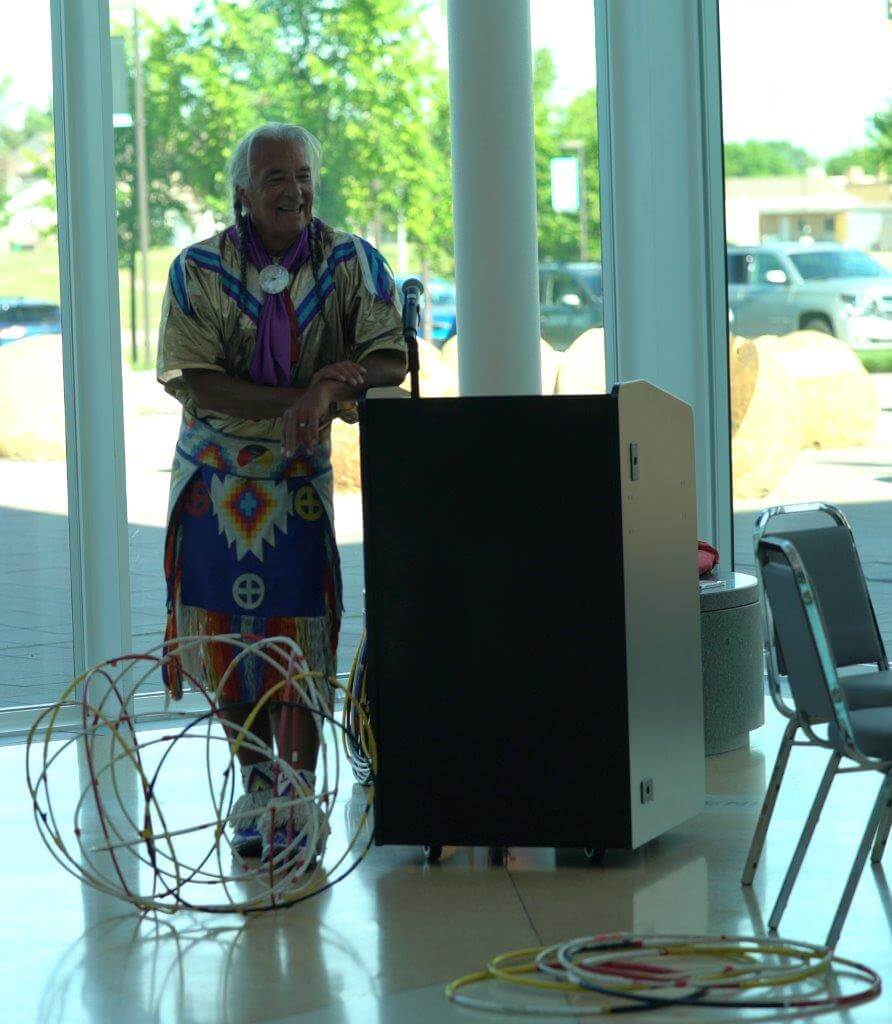

Kevin Locke, Lakota and Anishnabe, is a world-famous Hoop Dancer, flute player, traditional storyteller, cultural ambassador, recording artist and educator. Here he speaks of his cultural traditions and view of this North Grand Valley where significant historic events have occurred. Photo KBW.

Local school buses bring participants here on the last leg—on rougher roads—to the top of the ridge for a spectacular view of the North Grand drainage. These US Forest Service lands are managed with a dual purpose—for cattle grazing and public recreation.

While camping here, Native American women and children undoubtedly dug ‘Indian Turnips’ here, where they still grow abundantly. Photo JK.

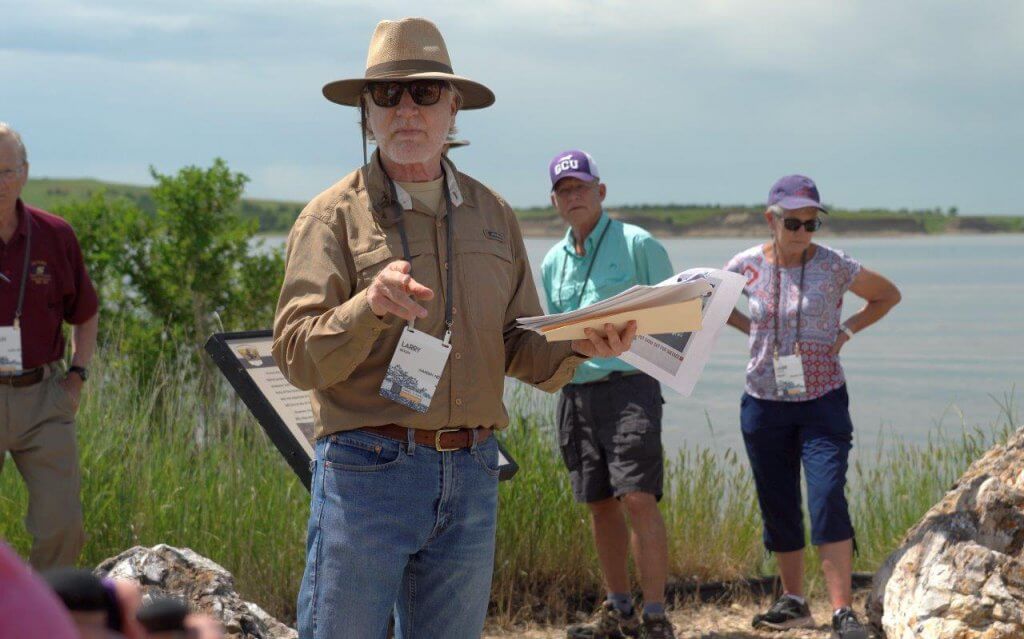

Over 90 people enjoyed the final bison supper of the BSC Buffalo Symposium at Dakota Buttes Museum Friday evening catered by The Peacock of Hettinger. Larry Skogen, center, thanks the people who made this happen and all who attended. Photo KBW.

Then everyone took a second look at Prairie Thunder, the museum’s full-size mounted buffalo bull, and climbed back on the buses for Bismarck. Photo JK.

Day 3—Saturday, June 25, 2022

On the third day, participants brought grandchildren to the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum for hands-on activities, treasure hunts, crafts and discoveries as well as gallery excursions and learning experiences for everyone.

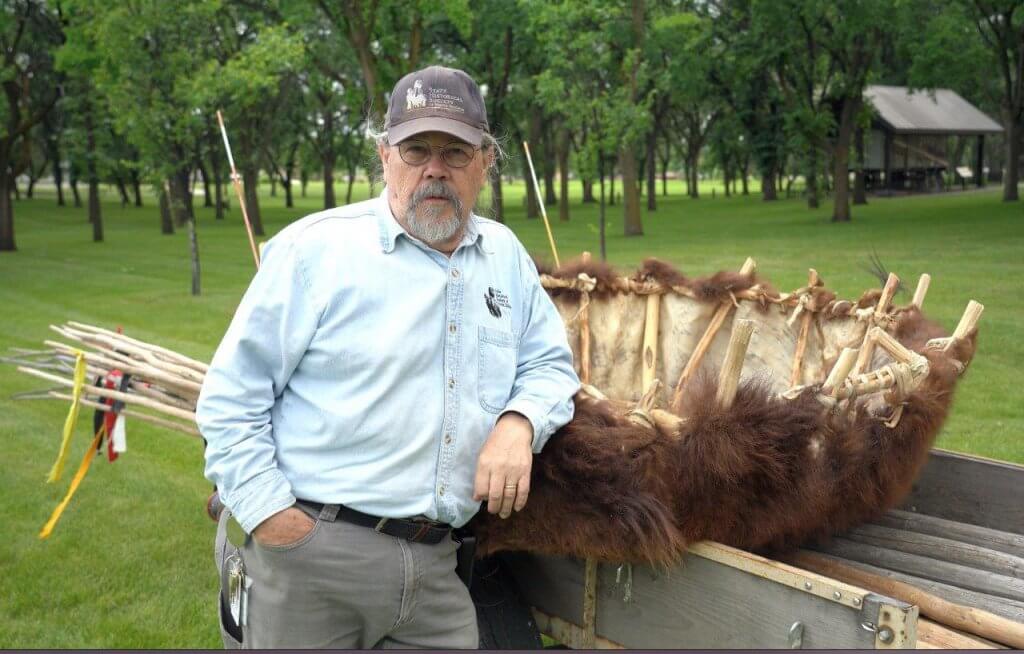

Erik Holland discusses the bullboat—often used by Mandans in crossing the Missouri River and hauling goods short distances by water. It was shaped of a single buffalo hide stretched and dried over willow framework—hair to the outside and tail left on. Photo JK.

In demonstration of proper tipi set-up on the ND Heritage Center lawn, the more recently used canvas covering is compared with a traditional cover made of buffalo hides. Photo JK.

Buffalo hide, bones and artifacts found in North Dakota are displayed and gently handled outside the Heritage Center on a warm and sunny Saturday morning in June. Photo JK.

Holland discusses the finer details of the large original painting depicting traditional homes in a Mandan village. The wall mural was painted on site. Photo JK.

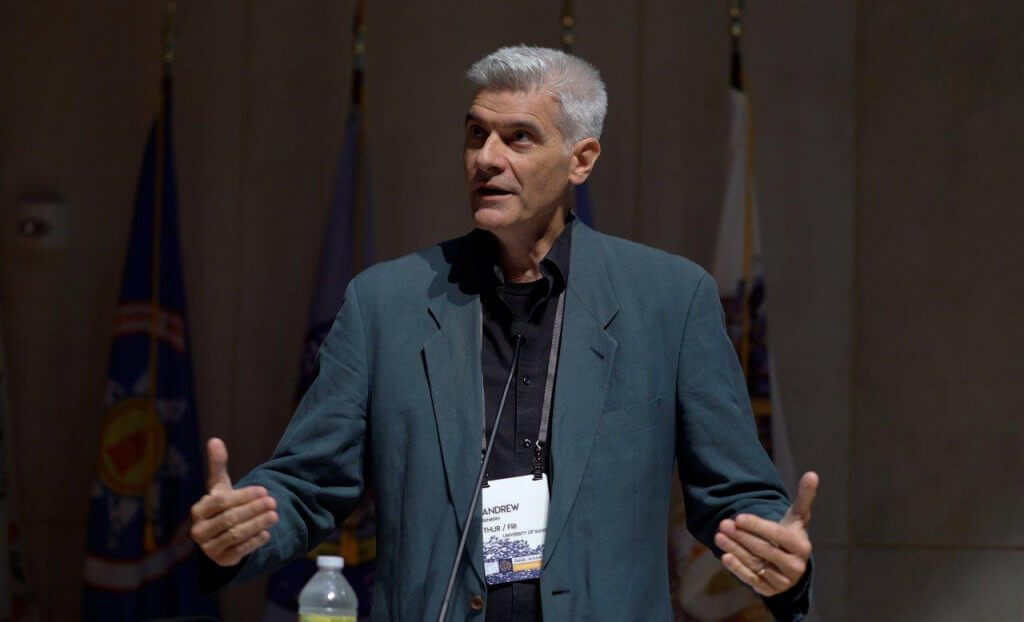

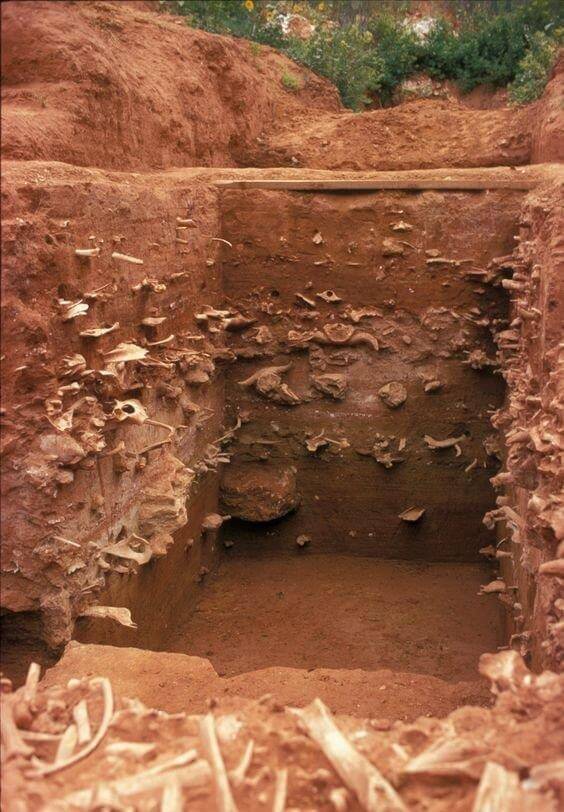

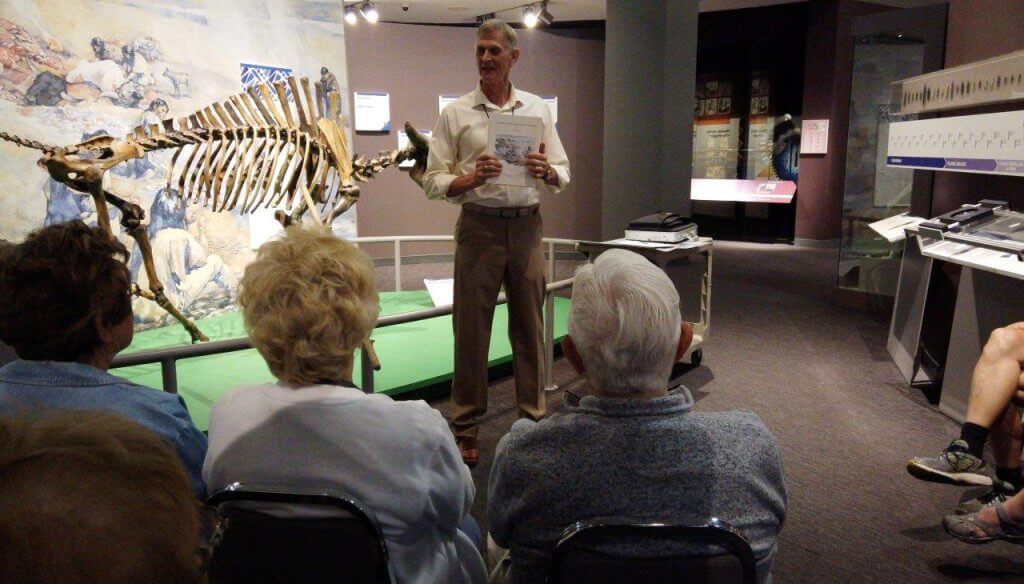

A volunteer with the State Historical Society explained the archeological study at Beacon Island in Lake Sakakawea. Excavation at the site revealed that roughly 10,000 years ago “hunters killed at least 29 Bison antiquus in early-to mid-winter (November to January) and the carcasses were moved a short distance for processing. The archeological record indicates the hunters butchered some of the animals on-site, preparing and packing a portion of meat for transport, breaking open log bones with cobble to extract marrow, and re-tooling for the next kill.” Photo JK.

Lots of things to do at the Heritage Center for young people. Paying close attention to a speaker are these two children. Photo JK.

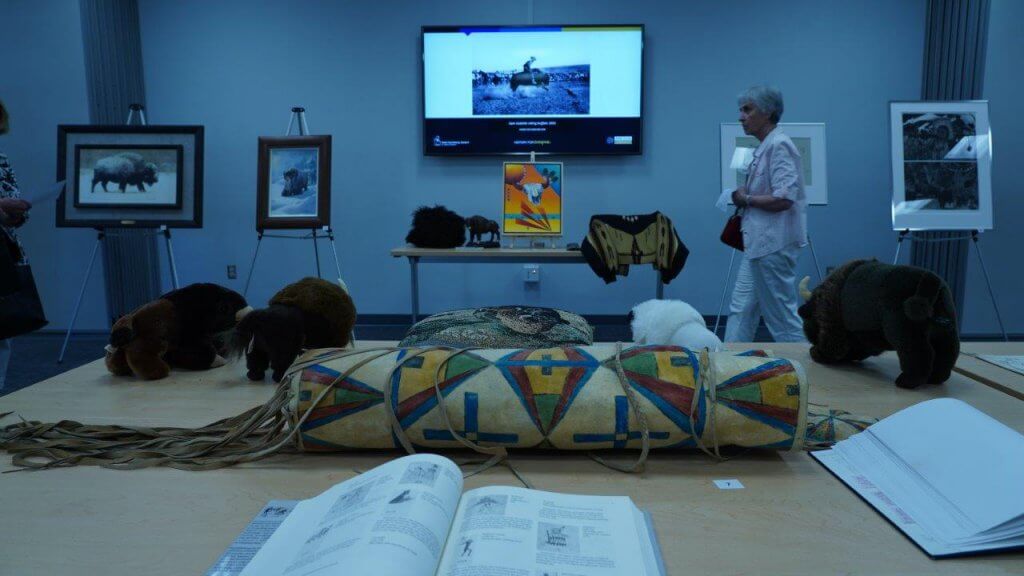

Bison Art Room: Andrea Fagerstorm, BSC art faculty member, organized a wonderful art display that included bison-themed art from a number of contributors including ten from Dr Thomas Jacobson, Hettinger, the Northwest Arts Center at Minot State University, Dakota Goodhouse, one of the presenters, and others. Included in the art room was a buffalo music display on loan from the National Buffalo Museum in Jamestown. Photo JK.

Tom Jacobsen, MD, discusses his Ledger Art and other early Sioux paintings that his great-aunt, Mary C. Collins, Congregational missionary from 1885 to 1910, collected from Native Americans on the Great Sioux Reservation at Little Eagle, SD. These two paintings depict Buffalo Hunts. Mary was the niece of his grandmother Ethel Collins, who came to teach at Day School in little Eagle from 1889 to 1892, before her marriage. Photo JK.

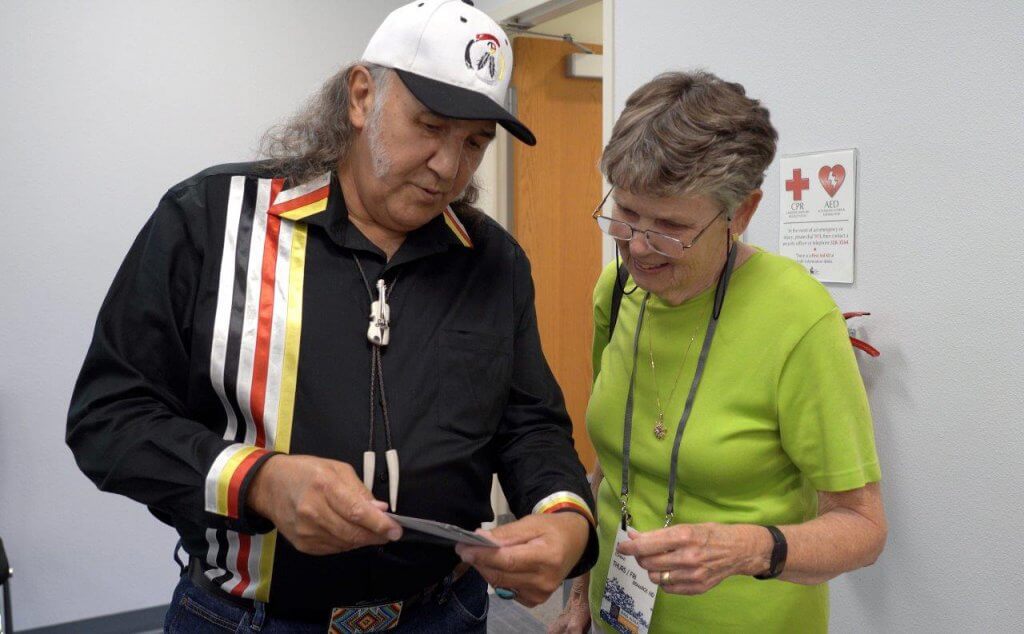

Les Thomas, North Dakota Native Tourism Alliance Board Vice President, engages with a participant and discusses the mystic of a white buffalo painting, Photos JK.

Floral bison quilt stitched by Val Braun of Hettinger depicts the Last Great Wild Buffalo Hunt that took place near there at the Sitting Bull Hunt Site on October 12 and 13, 1883. Photo JK.

Participants take time for a mid-morning break to get better acquainted with new friends and discuss their special interests with various experts. Photo JK.

by Francie M Berg 7/5/2022

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog