Big buffalo herds ranged over the buttes and badlands of Monana and the western Dakotas until the 1880s. Photo by Jim Kambeitz.

My interest in buffalo began when I rode the buttes and badlands of our ranch east of Miles City, MT as a kid.

One time my younger sister Anne and I found a buffalo skull.

The snow melted early that spring, sending rushing waters to flush out dry creek beds.

Riding the higher reaches of our range we were looking for a lost heifer.

In a glint of bright sunlight we saw something peeking out from under a sagebrush that had been partly torn loose from a sandy bank.

“What’s that?” Anne circled her horse across the gravel creek bed.

“Looks like a bone—a horn.”

Sliding off our horses we scrambled up the bank for a closer look.

Yes! Not just a horn—but a horn solidly attached to the rest of the head. As we freed it from the scraggly sagebrush tangle, out came a nearly perfect skull with stout curved horns—gleaming white in the sun. We hefted the weight of it, bigger and bulkier than any skull we had ever seen.

Which Skull is best??

A relic of long ago—a buffalo skull. The black horn caps had loosened and washed away in the 70-some years since wild buffalo had roamed these ranges.

In the 1940s it had been only 70 years since the huge herds of buffalo grazed those ranges.

We’d seen the famous photos of dead buffalo, slaughtered across this very range by hide hunters, as photographed by L.A. Huffman. He set up his studio in our town, Miles City, just in time to record that final kill.

LA Huffman arrived in Miles City just in time to film the last slaughter of the great herds. Photo by LA Huffman, 1880.

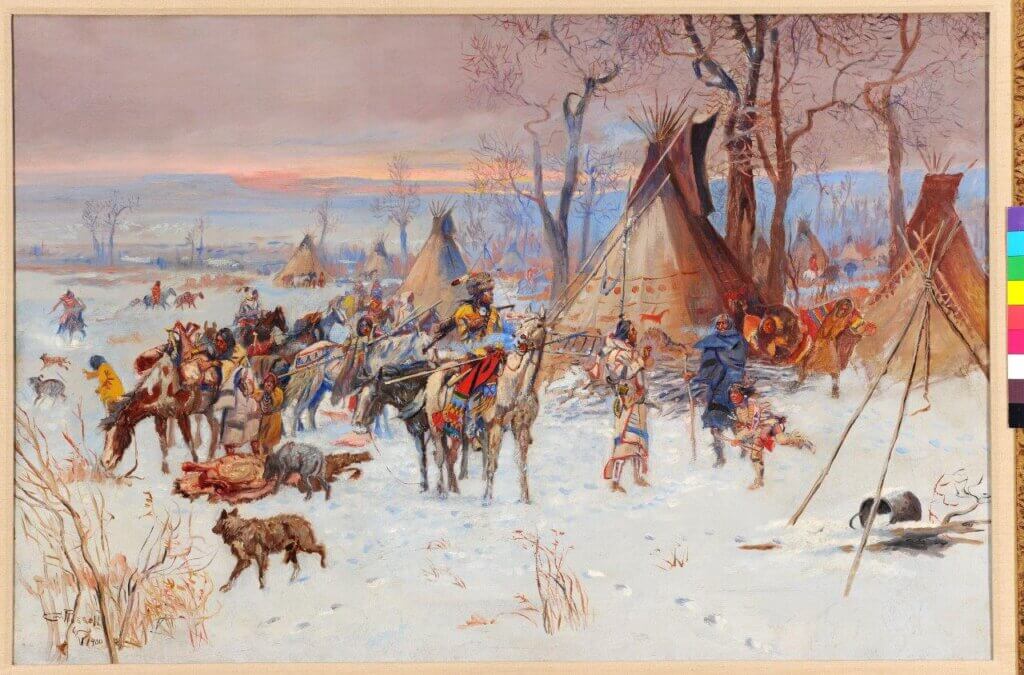

Safe on Great Sioux Reservation, 1880

The southern herd was already gone.

Buffalo didn’t migrate north in the fall. But by all accounts, these last buffalo did. This last desperate herd of around a hundred thousand buffalo weren’t seeking warmer climate that fall, but safety.

Blazing guns right behind, they trekked up from Wyoming and hit the little cow town of Miles City on the run.

When they hit the Yellowstone River, half the big herd plunged in, swam across and travelled north—right into the fierce guns of hundreds of white and Native hide hunters. They didn’t survive long. Within months all were gone.

Some wild instinct led the other half—the last big herd of many millions—more directly northeast—on our side of the Yellowstone, the south side.

Apparently, they turned east where the Powder River and O’Fallon Creek flowed into the Yellowstone River, then followed those plateaus and valleys into Dakota Territory.

There they found safety for a time in the pine hills of the Slim Buttes. And just beyond that, onto the Great Sioux Indian Reservation.

The last big herds found safety for a time on the Great Sioux Indian Reservation where white hide hunters were not allowed. Photo by Kathy Berg Walsh.

This was about 150 miles east of Miles City on the border of what became North and South Dakota, where these last 50,000 from the great northern herd made their last stand.

That big old sagebrush stood along their trail. We’d ridden past it dozens of times. Anne and I wrapped the skull in a jacket and tied it behind my saddle.

At home we cleared a place in Mom’s flower garden near our front door, next to her yellow rosebush.

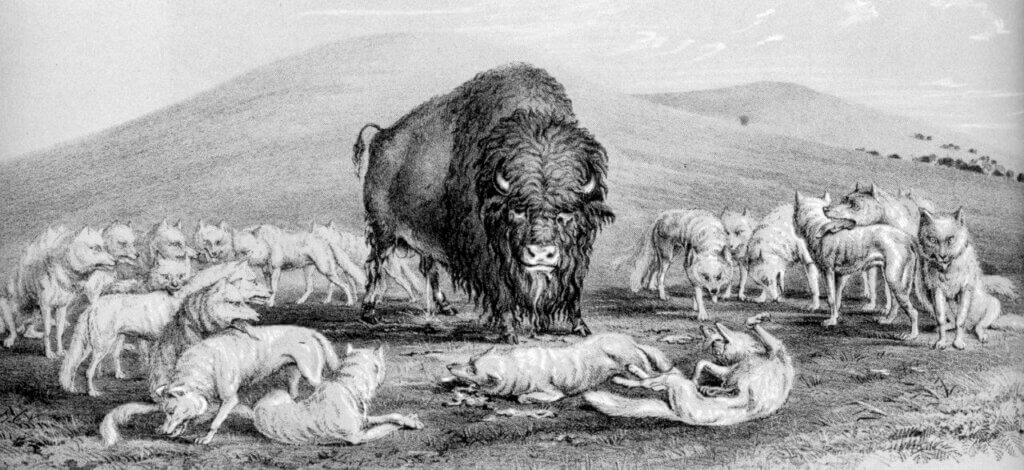

Hungry wolf packs followed the wild buffalo herds and picked off the old and weak who did not keep up. Alone, they didn’t last long. Catlin sketch from David Dary.

Many times our family and visitors speculated and argued over how that old bull had lived and died.

Searching Local History

Years later when our family moved to Hettinger ND the summer of 1966, my husband Bert as the new veterinarian was eager to help local ranchers care for their cattle, horses, sheep, sheep dogs. And, yes, a few herds of buffalo.

We didn’t know we were coming to the place where those very buffalo from Miles City had made their last stand in 1880.

We built our home at the edge of town with barn, corrals and 40 acres of pasture. We also didn’t know that my grandparents—the Tom Barretts had staked out their first homestead claim on Lodgepole Creek where it flowed into the South Grand River. They lived in a dugout in the side of a hill.

As newcomers to Hettinger we heard a few rumblings from old-timers. “The last big buffalo hunts were here,” they told us.

“What? What do you mean?” we asked. “The last hunts where? In North America? Or in North Dakota?”

“I don’t know—that’s what they say,” came the inevitable answer.

I wanted to know more. What did that mean? I started a search. I wanted to read it in a book.

Sure enough, several books held promise—claiming special knowledge of the very last hunts. But their “last hunt” always turned out to be the worst scenario—big guns, big slaughter, rotting carcasses left all across the Plains—in Kansas or somewhere else even farther south.

Everyone knew that shameful history, the scar on our national wildlife story. Depressing.

Three Last Hunts

Then one day, browsing our local library, I came across a little-known book of memoirs, My Friend the Indian, by James McLaughlin, Indian Agent at Ft. Yates.

Flipping pages, back to front, I found myself reading an amazing tale in a chapter called “The Great Buffalo Hunt.”

Suddenly there it was—all laid out, step by step—the Hiddenwood hunt in complete and fascinating detail by a man who was here and on that hunt.

McLaughlin described the Native march out of Fort Yates, all resplendent in their best hunting attire.

Six hundred mounted riders wove in and out among those walking and riding in buckboard wagons, their prancing horses painted in traditional ways, as they struck out for the ancient buffalo ranges 100 miles away—to Hiddenwood Cliff right in our Hettinger community.

McLaughlin hunted here, with 2,000 Native Americans, right outside our living room window, riding up Hiddenwood Creek, which runs through our town.

Later another jewel appeared in a dusty collection. The memoirs of a Congregational Missionary Thomas Riggs, stationed at Oahe offered another Buffalo Hunt section.

Again, an amazing story, told by an articulate and sympathetic man who was there—with a small band of traditional Lakota hunters on a long, cold winter hunting adventure in the pine hills of the Slim Buttes.

The missionary Thomas Riggs spent three months with traditional Lakota hunters on one of the last great hunts in the Slim Buttes. Photo courtesy Montana Hist Soc.

Riggs described the trip—religious traditions held along the way. Thanks and prayers to Mother Earth and to the Buffalo themselves for their generosity in caring for their human relatives.

Both these hunts were traditional, conducted with religious fervor and ancient ceremony. Both fit perfectly into William Hornaday’s well-documented history of 1889, The Extermination of the American Bison.

William Hornaday reported the final hunt of the big herds happened when Sitting Bull and his band arrived in Oct 12 and 13, 1883. “There was not a hoof left!” he wrote. Photo by J Schmidt, NPS.

After the wild herds were gone the Smithsonian Museum sent Hornaday—their leading taxidermist—out west to report how this buffalo destruction could have possibly happened and to bring back some museum-worthy carcasses if possible.

In researching his book, Hornaday really thought he was writing about the final hours of what he called “this magnificent animal.” Determined to get it right, he spared no effort in contacting every possible source of buffalo knowledge, from Army officers at far-flung western forts to fur traders, railroaders, hide hunters and cowboys.

Hornaday learned that the end came right here, but offered few details. Except he wrote that Sitting Bull was right here at the end and his band killed the last 1,200 buffalo. He even had the exact dates—October 12 and 13, 1883.

These last buffalo hunt details were virtually unknown in 1995. Just word of mouth stories from pioneers who settled here on what had been once designated Indian reservation lands by treaty.

Someone needed to get all this together on paper. But it seemed no one was interested. This history would soon be forgotten. If I didn’t write it, who would?

From these three sources came our small book, in which I brought together for the first time the full story of the last stand of the American buffalo and their last dramatic moments The Last Great Buffalo Hunts: Traditional Hunts in 1880 to 1883 by Teton Lakota People.

Our Dakota Buttes Visitors Council of which I had been a charter member since arriving in Hettinger agreed to pay for printing and distribution.

We sponsored free tours of our Last Hunt Sites. Photo at left the Sitting Bull Site. At right Historic Site Hiddenwood Cliff can be seen in distance at right. Photos KBW.

We started taking local people on bus tours of our three Historic Last Great Traditional Native Hunts. For the first time ever people learned the full story of the last stand of the American buffalo and these last dramatic moments.

Buffalo have always grazed these western lands. Courtesy SD Tourism.

It was a heroic legacy told by Native Americans and early settlers. Until then, somehow this final triumph of the buffalo saga fell through the cracks in our national and state histories.

End of story.

But wait! There’s more.

______

NEXT

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog

Great article Francie. Hope to pass that way in late summer after crossing Canada on the Trans Canadian Highway. Currently reading Alexander Henry the Younger’s Journals. Mind boggling the herds that existed in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Thank you, Michael

Hi Michael

Thanks again for visiting our historic buffalo sites. Glad you’ll be returning. It’s difficult to see all our buffalo sites all at once, and to wrap your mind around them. It’s too much. And now we’ve identified buffalo trails and wallows!

Best Wishes, Francie

Loved reading your story this morning Francie. I’ve been to the High Divide north & west of Miles City where Hornaday got the specimins. Your story brings it all to light.

Thanks,

P.S. my dad’s name was Bert

Hi Doc Woerner

Nice to hear from you again. So now you’ve seen where I was born at home on a cattle/sheep ranch in the rugged Missouri River Breaks. In a house built from Cottonwood logs hauled up from the Missouri River alfalfa flats. During the worst time of the depression and drought. No wonder my folks looked for irrigated land on the Yellowstone River!

Francie

Your articles on the West are so rich in local history and detail from those that lived it! I enjoy each one, thank you. The ones on the last buffalo are fancinating. You think we could learn from history to treasure what we have and protect- seems not. Maybe there are some that will make a difference after reading these stories. Thank you again for sharing. It is so important to share and spread the experiences. Let they be known.

It’s great to hear from you, Kate! We all have much to learn if we want to know and understand the magnificent buffalo and their long history interlinked with human culture and belief. Learning is a real pleasure, isn’t it! Thanks for writing.

Sincerely, Francie