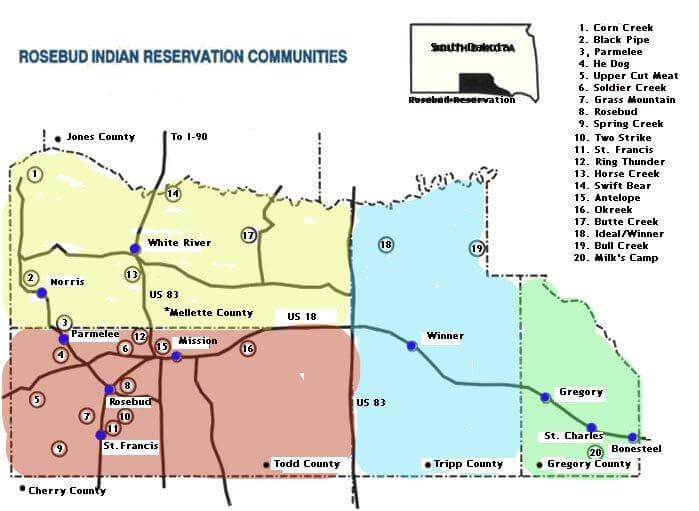

There are many versions of the White Buffalo Woman tradition, passed down in the Lakota Sioux culture from one storyteller to another. This version was told by John Fire Lame Deer at Winner on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, 1967. Although the White Buffalo Woman tradition differs in details, at its core it is the same—and each telling adds yet another layer of beauty to the traditional story.

Storytelling was an important way Native traditions and history were passed down through the generations. John Fire Lame Deer told of the White Buffalo Calf Woman tradition at a gathering in Winner in 1967.

One summer so long ago that nobody knows how long, the Oceti-Sakowin, the seven sacred council fires of the Lakota Oyate, the nation, came together and camped.

The sun shone all the time, but there was no game and the people were starving. Every day they sent scouts to look for game, but the scouts could find nothing.

Among the bands assembled were the Itazipcho, the Without-Bows, who had their own camp circle under their chief, Standing Hollow Horn.

Early one morning Chief Standing Hollow Horn sent two of his young men to hunt for game.

They went on foot, because at that time the Sioux didn’t yet have horses. They searched everywhere but could find nothing.

Seeing a high hill, they decided to climb it so they could look over the whole country. Halfway up, they saw something coming toward them from far off, but the figure was floating instead of walking.

Map of the Rosebud Reservation communities covers four counties in South Dakota. At a 1967 gathering in the town of Winner, Tripp County, John Fire Lame Deer told of the White Buffalo Calf Woman tradition on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

From this they knew that the person was “wakan”—or holy.

At first they could make out only a small moving speck and had to squint to see that it was a human form. But as it came nearer, they realized that it was a beautiful young woman, more beautiful than any they had ever seen, with two round, red dots of face paint on her cheeks.

She wore a wonderful white buckskin outfit, tanned until it shone a long way off in the sun. It was embroidered with sacred and marvelous designs of porcupine quill, in radiant colors no ordinary woman could have made.

This wakan stranger was Ptesan-Wi, White Buffalo Calf Woman.

In her hands she carried a large bundle and a fan of sage leaves. She wore her blue-black hair loose except for a strand at the left side, which was tied up with buffalo fur. Her eyes shone dark and sparkling, with great power in them.

The two men looked at her with mouths open. One was overawed, but the other desired her body and stretched his hand out to touch her.

This woman was ‘lila wakan,’ very sacred, and could not be treated with disrespect.

Lightning instantly struck the brash young man and burned him up, so that only a small heap of blackened bones was left. Or some say that he was suddenly covered by a cloud, and within it he was eaten up by snakes that left only his skeleton, just as a man can be eaten up by lust.

To the other scout who had behaved well, the White Buffalo Calf Woman said, “Good things I am bringing, something holy to your nation. A message I carry for your people from the buffalo nation.

“Go back to the camp and tell your people to prepare for my coming. Tell your chief to put up a medicine lodge with 24 poles. Let it be made holy for my coming.”

This young hunter returned to the camp. He told the chief, he told the people, what the sacred woman had commanded.

The chief told the ‘eyapaha,’ the crier.

And the crier went through the camp circle calling: “Someone sacred is coming. A holy woman approaches. Make all things ready for her.”

So the people put up the big medicine tepee with 24 poles and waited. After four days they saw the White Buffalo Calf Woman approaching, carrying her bundle before her.

Her wonderful white buckskin dress shone from afar. The chief, Standing Hollow Horn, invited her to enter the medicine lodge. She went in and circled the interior in the direction the sun moves through the sky.

The chief addressed her respectfully, saying: “Sister, we are glad you have come to instruct us.”

She told him what she wanted done. In the center of the tepee they were to put an ‘owanka wakan,’ a sacred altar, made of red earth, with a buffalo skull and a three- stick rack for a holy thing she was bringing.

They did as she directed, and she traced a design with her finger on the smoothed earth of the altar.

She showed them how to do all this, then circled the lodge again in the same direction. Halting before the chief, she now opened the bundle. The holy thing it contained was ‘chanunpa,’ the sacred pipe.

She held it out to the people and let them look at it. She was grasping the stem with her right hand and the bowl with her left, and thus the pipe has been held ever since.

Again the chief spoke, saying: “Sister, we are glad. We have had no meat for some time. All we can give you is water.”

They dipped some ‘wacanga,’ sweet grass, into a skin bag of water and gave it to her, and to this day the people dip sweet grass or an eagle wing in water and sprinkle it on a person to be purified.

White Buffalo Calf Woman showed the people how to use the pipe. She filled it with ‘chan-shasha,’ red willow-bark tobacco.

She walked around the lodge four times after the manner of Anpetu-Wi, the great sun. This represents the circle without end, the sacred hoop, the road of life.

The woman placed a dry buffalo chip on the fire and lit the pipe with it. This was ‘peta-owihankeshni,’ the fire without end, the flame to be passed on from generation to generation.

In the holy woman tradition the White Buffalo Woman brought the Pipe and showed the Lakota how to use it in a prayerful way. In this 1898 photo, Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud smokes the pipe on the South Dakota Rosebud Reservation. Photo by Jesse H. Bratley.

She told them that the smoke rising from the bowl was Tunkashila’s breath, the living breath of the great Grandfather Mystery.

The White Buffalo Calf Woman showed the people the right way to pray, the correct words and the gestures to use.

She taught them how to sing the pipe-filling song and how to lift the pipe up to the sky, toward Grandfather, and down toward Grandmother Earth, to Unci, and then to the four directions of the universe.

“With this holy pipe,” she said, “you will walk like a living prayer. With your feet resting upon the earth and the pipe stem reaching into the sky, your body forms a living bridge between the Sacred Beneath and the Sacred Above.

“Wakan Tanka smiles upon us, because now we are as one—earth, sky, all living things, the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged ones, the trees, the grasses. Together with the people, they are all related, one family. The pipe holds them all together.

“Look at this bowl,” said the White Buffalo Woman. “Its stone represents the buffalo, but also the flesh and blood of the red man. The buffalo represents the universe and the four directions, because he stands on four legs, for the four ages of creation.

“The buffalo was put in the west by Wakan Tanka at the making of the world, to hold back the waters. Every year he loses one hair, and in every one of the four ages he loses a leg.

“The sacred hoop will end when all the hair and legs of the great buffalo are gone, and the water comes back to cover the Earth. The wooden stem of this ‘chanunpa’ stands for all that grows on the earth.

“Twelve feathers hanging from where the stem—the backbone—joins the bowl—the skull—are from Wanblee Galeshka, the spotted eagle, the very sacred bird who is the Great Spirit’s messenger and the wisest of all flying ones. You are joined to all things of the universe, for they all cry out to Tunkashila.

“Look at the bowl: engraved in it are seven circles of various sizes. They stand for the seven sacred ceremonies you will practice with this pipe, and for the Oceti Sakowin, the seven sacred campfires of our Lakota nation.”

The White Buffalo Calf Woman then spoke to the women, telling them that it was the work of their hands and the fruit of their bodies which kept the people alive.

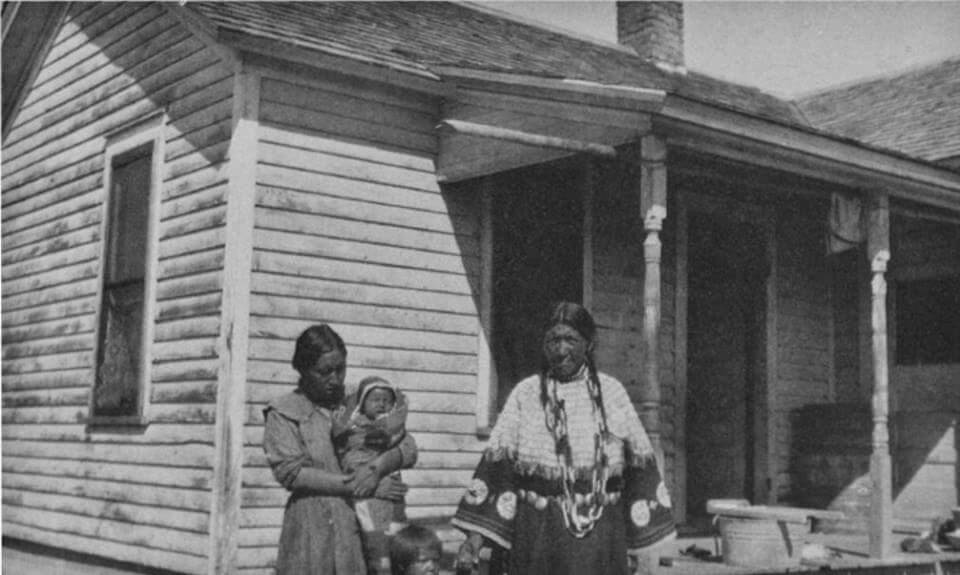

The White Buffalo Woman told Native American women “You are from Mother Earth. What you are doing is as great as what the warriors do.” In this 1923 photo Sicangu women with baby and young child show off their fine clothing on Rosebud Reservation.

“You are from the mother earth,” she told them. “What you are doing is as great as what the warriors do.”

And therefore the sacred pipe is also something that binds men and women together in a circle of love.

Man and woman with tepee. When a man takes a wife, they both hold the pipe at the same time and red trade cloth is wound around their hands, thus tying them together for life, said the White Buffalo woman. This photo is said to be of a Lakota wedding, possibly taken on the Rosebud reservation about 1912. Credit Tuell.

It is the one holy object in the making of which both men and women have a hand. The men carve the bowl and make the stem; the women decorate it with bands of colored porcupine quills.

When a man takes a wife, they both hold the pipe at the same time and red trade cloth is wound around their hands, thus tying them together for life.

The White Buffalo Woman had many things for her Lakota sisters in her sacred womb bag— corn, ‘wasna’ (pemmican), wild turnip. She taught them how to make the hearth fire.

She filled a buffalo paunch with cold water and dropped a red-hot stone into it. “This way you shall cook the corn and the meat,” she told them.

The White Buffalo Calf Woman also talked to the children, because they have an understanding beyond their years.

She told them that what their mothers and fathers did was for them, that their parents could remember being little once, and that they, the children, would grow up to have little ones of their own.

She told them: “You are the coming generation, that’s why you are the most important and precious ones. Some day you will hold this pipe and smoke it. Some day you will pray with it.”

She spoke once more to all the people: “The pipe is alive; it is a red being showing you a red life and a red road. And this is the first ceremony for which you will use the pipe. You will use it to keep the soul of a dead person, because through it you can talk to Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery Spirit.

The Buffalo woman spoke to the people telling them that they were the purest among tribes and that is why they were chosen to be caretakers of the pipe for all people. This early photo shows a group of Sicangu Lakota men and women leaders from Rosebud Reservation.

“The day a human dies is always a sacred day. The day when the soul is released to the Great Spirit is another. Four women will become sacred on such a day. They will be the one to cut the sacred tree—the ‘can-wakan’—for the sun dance.”

She told the Lakota that they were the purest among the tribes, and for that reason Tunkashila had bestowed upon them the holy ‘chanunpa,’ They had been chosen to take care of it for all the Indian people on this turtle continent.

She spoke one last time to Standing Hollow Horn, the chief, saying, “Remember: this pipe is very sacred. Respect it and it will take you to the end of the road.

“The four ages of creation are in me; I am the four ages. I will come to see you in every generation. I shall come back to you.”

The sacred woman then took leave of the people, saying: “Toksha ake wancinyankin (wacinyanktin) ktelo—I shall see you again.”

The people saw her walking off in the same direction from which she had come, outlined against the red ball of the setting sun.

As she went, she stopped and rolled over four times. The first time, she turned into a black buffalo; the second into a brown one; the third into a red one. And finally, the fourth time she rolled over she turned into a white female buffalo.

The fourth time she rolled over, the White Buffalo Woman turned into a white buffalo and disappeared over the horizon. Credit White Cloud mounted in the National Buffalo Museum, Jamestown Sun.

A white buffalo is the most sacred living thing you could ever encounter. The White Buffalo Calf Woman disappeared over the horizon. Sometime she might come back.

Great herds of buffalo came to the Lakota in the White Buffalo woman tradition—and she brought many other gifts. Today Native Americans celebrate their modern tribal Buffalo herd on the Rosebud Indian Reservation—as on most other reservations in the Plains states. Credit Rosebud Tribe.

As soon as she had vanished, buffalo in great herds appeared, allowing themselves to be killed so that the people might survive.

And from that day on, our relatives, the buffalo, furnished the people with everything they needed—meat, skins for their clothes and tepee’s and bones for their many tools.

Other versions:

www.ilhawaii.net/~stonylore30

www.blackelkspeaks.unl.edu/appendix2

www.think-aboutit.com

NEXT: Buffalo Trucker for 24 Years

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog