In essence, the saving of buffalo focused on two major factors.

On the one hand were westerners, both Native American and whites, who saw what was happening to the buffalo and cared about saving them.

With boots on the ground, these people rescued, nourished and protected fragile buffalo calves until they multiplied into healthy and prolific herds.

Without them American bison would likely have gone extinct. There’d be no buffalo in North America today. It almost happened.

On the other hand were outstanding Conservationists from the east—who came west to hunt buffalo, yes—but who also understood what was going on and fought for refuges and wildlife parks where they could live out their lives in safety.

The Buffalo Conservationists we know best are President Theodore Roosevelt, William Hornaday and George Bird Grinnell. Each made a significant impact on wildlife conservation in the United States—particularly on buffalo.

As young men, their early lives were influenced by nature, by wildlife—and by the west and western values.

Theodore Roosevelt Travels West

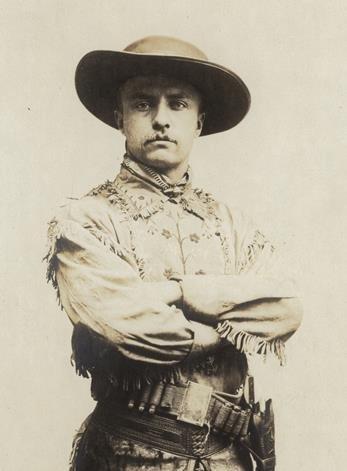

Theodore Roosevelt came west to hunt buffalo at age 24—just as the last of the great wild herds vanished forever. He nearly missed them all together.

Roosevelt was considered an eastern dude when he arrived in Medora. But he learned to love the badlands, developed a broad-minded viewpoint as a rancher, became an advocate for the strenuous life and the Conservationist President of the United States.

In fact, he arrived on September 8, 1883 in Medora, Dakota Territory, on the newly finished stretch of the Northern Pacific railway. It was only a month later—in mid-October—that Sitting Bull and his band killed the last 1,200 wild buffalo ranging on the nearby Great Sioux Reservation.

Born in 1858 in New York City into a wealthy family, he struggled as a frail child, was taught by a private tutor and quickly discovered a passion for the outdoors and nature.

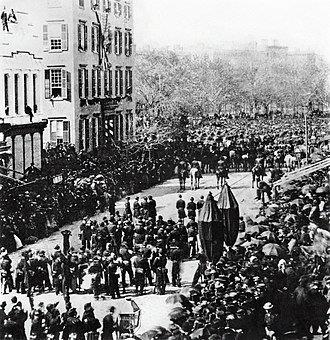

A 6-year-old Roosevelt with his younger brother Elliott watched Lincoln’s funeral procession from the second-floor window of their grandfather’s mansion (building at center far left). Photographed at the window, as confirmed by wife Edith, who was also there as a childhood friend. Manhattan, April 25, 1865.

His favorite activities included hiking, rowing, swimming, riding, bird-watching, hunting and taxidermy.

Creating a vast collection of specimens, he filled his boyhood home and later his adult estate with insect collections and mounted animals. Some are still on display in the Smithsonian.

Roosevelt’s youth was dominated by poor health and asthma. He suffered sudden nighttime asthma attacks that terrified both him and his parents. Doctors had no cure. Here photographed in Paris at age 11.

Roosevelt graduated from Harvard and studied law at Columbia. In 1880 he married Alice Lee, a socialite he met there.

Then, deciding not to finish law school, he took an opportunity that opened to him in politics.

Elected as a Republican to the New York State Assembly at 23, Roosevelt quickly made a name for himself as a foe of corrupt machine politics.

In Medora Roosevelt found and hired a local guide, Joe Ferris. Riding horseback on a 10-day hunt well outside the reservation they flushed out a few lone bulls and one small band of buffalo in the badlands of the Little Missouri River Valley, southwest of Medora.

In his book The Works of T Roosevelt, Memorial Edition, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, Roosevelt writes about that hunting adventure.

As he relates it, the first buffalo bull they saw plunged out of a little side coulee, taking both he and the guide by surprise.

“A shabby looking old bull bison galloped out and, without an instant’s hesitation, plunged over a steep bank into a patch of broken ground around the base of a high butte.

“So quickly did he disappear that we had not time to dismount and fire. Getting our horses over the broken ground as fast as possible, we rode round the butte only to see the buffalo come out and climb up the side of another butte over a quarter of a mile off.

“In spite of his great weight and cumbersome, heavy gait, he climbed up the steep bluff with ease and even agility, and when he had reached the ridge stood and looked back at us for a moment.

“In another second he made off . . . he must have traveled a long distance before stopping, for we followed his trail for some miles, yet did not again catch so much as a glimpse of him.”

Later they saw three black specks—three more old bulls. They dismounted and crawled on hands and knees.

“We got within about 125 yards and as all between was bare ground I drew up and fired. The bullet told on his body with a loud crack, the dust flying up from his hide; but did not in the least hinder him, and away went all three with their tails up.

“I drew up and fired. The bullet told on his body . . . but did not in the least hinder him, and away went all three with their tails up.” Credit Missoulian, Kurt Wilson.

“For seven or eight miles we loped our jaded horses, occasionally seeing the buffalo far ahead.

“When the sun had just set, we saw all three had come to a stand in a gentle hollow. They faced us and made off, while the ponies put on a burst that enabled us to close in with the wounded one.

“Within 20 feet I fired my rifle, but the darkness and violent labored motion of my pony made me miss.

“I tried to get in closer, when suddenly up went the bull’s tail and, wheeling, he charged with lowered horns. My pony spun round and tossed his head.

“My companion jumped off and took a couple of shots, missed in the dim moonlight and to our unutterable chagrin the wounded bull vanished in the darkness.

A day or so later in the rain they came over a low divide and saw black objects in the distance. Again they crept toward them on hands and knees upwind.

“The rain was beating in my eyes and the drops stood out in the sights of the rifle so I could hardly draw a bead—and I either overshot or else at the last moment must have given a nervous jerk and pulled the rifle clear off the mark.

“At any rate, I missed clean and the whole band plunged down into a hollow and were off before I could get another shot.”

Finally, on the 10th day they passed the mouth of a steep ravine along the Little Missouri River, on Cannonball Creek, close to the Montana border.

Suddenly both horses threw up their heads and looked with alarm toward the head of the gully.

“I slipped off and ran quickly but cautiously up along the valley. Before I had gone a hundred yards, I noticed in the soft soil at the bottom the round prints of a bison’s hooves and immediately afterward got a glimpse of the animal himself—a great bison bull—as he fed slowly up the ravine not 50 yards off.

“As I rose above the crest of the hill he held up his head and cocked his tail in the air. Before he could get off I put the bullet in behind his shoulder.

“The wound was an almost immediately fatal one.

“Yet with surprising agility for so large and heavy an animal, he bounded up the opposite side of the ravine, heedless of two more balls, both of which went into his flank and ranged forward—and disappeared over the ridge at a lumbering gallop, the blood pouring from his mouth and nostrils.

“In the next gully we found him stark dead, lying almost on his back, having pitched over the side when he tried to go down it.

“He was a splendid old bull, still in his full vigor, with large, sharp horns and heavy mane and glossy coat, and I felt the most exulting pride as I handled and examined him.”

Roosevelt shot his buffalo on September 20, 1883 on upper Little Cannonball Creek near where it is joined by the Little Missouri, just across the Dakota Territorial line into Montana, according to Joe Wiegand, Theodore Roosevelt scholar, who portrays TR with the Theodore Roosevelt Medora Foundation in Medora.

At the time Wiegand says Roosevelt and Joe Ferris were using the Nemilla Ranch as a base camp, hosted by Gregor Lang and his 16-year-old son Lincoln, north of today’s Marmarth, ND.

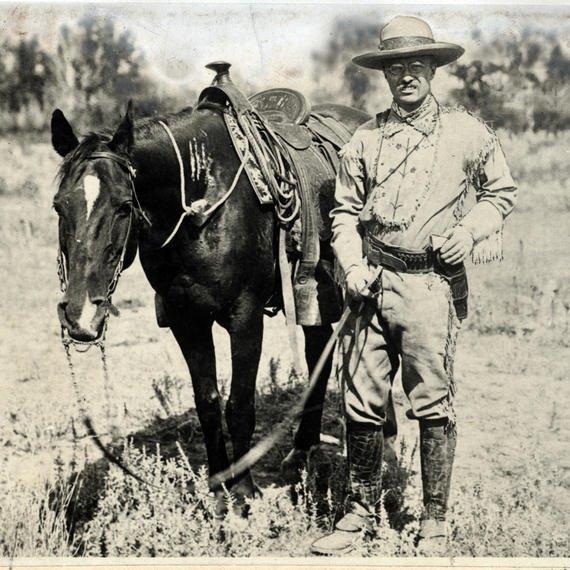

Roosevelt was so delighted with his hunting adventure in the scenic badlands with rugged buttes and fertile green bottoms all around that he impulsively decided to become a cattle rancher.

Painted Canyon, TR National Park, at sunset. Roosevelt was so delighted with his hunting adventures in the badlands with its rugged buttes and fertile green bottoms that he invested in two cattle ranches. Medora Foundation.

He invested in two cattle ranches—the Maltese Cross seven miles south of Medora and the Elkhorn, 35 miles north.

The next year TR suffered a double tragedy when his mother and his wife both died on the same day—Valentine’s Day. His wife had given birth two days before to a daughter, also named Alice.

He returned to Medora and spent much of the next two years on his ranch in the Badlands of Dakota Territory.

Roosevelt threw himself into ranching, determined to get a taste of the American frontier before it was gone forever, and to restore his health by living a vigorous life.

In Medora, Roosevelt lived in the saddle, learning to be an authentic cowboy, ranching, driving cattle, hunting—and at the same time overcame his physical weaknesses.

He fell in love with the Little Missouri badlands and admired the strenuous life of the outdoorsmen who lived and worked there, trying to follow their example.

In the North Dakota badlands he lived in the saddle, learning to be an authentic cowboy ranching, driving cattle—he even captured an outlaw and at the same time overcame his physical infirmities.

In Dakota Territory Roosevelt changed from the frail, New York “dude” who arrived there—into a democratic advocate for ranching and the strenuous life who became the 26th President of the United States.

William Hornaday Seeks Buffalo Carcasses

in 1886 William Temple Hornaday also came west to hunt buffalo—if he could find any.

As chief taxidermist of the Smithsonian Museum, when he learned that buffalo were almost extinct, he surveyed the Smithsonian’s storage closets for buffalo bones and carcasses.

Shocked, he found only one poorly mounted female, a few tattered bison hides and an incomplete skeleton.

How would future generations of Americans be able to visualize the magnificent mammal that once stampeded across the plains and prairies by the millions, if the greatest museums in the nation had none?

He wanted some buffalo carcasses for mounting, so that future Americans could view them.

William Hornaday and an unidentified man working in the taxidermy lab behind the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, DC. A bird hangs from the ceiling, and mounted animals line the shelves. Skulls and animal skins are scattered throughout the room. Credit Smithsonian Institution Archives, c. 1880.

Hornaday immediately requested permission to travel west to collect bison carcasses—dead buffalo—lots of them, preferably as many as 80. If that many still existed.

He planned to shape them into a dramatic new Smithsonian exhibit, unlike any seen before, and share the rest with the foremost museums in the United States, so that when buffalo became totally extinct—as he had no doubt would soon happen—future generations could still view the pinnacle of America’s great wildlife heritage.

Thus began Hornaday’s fascination with the buffalo that continued all his life.

Little did he know then that American Bison would become his obsession, that he’d spend the rest of his life fighting for their survival.

The last of the great wild buffalo herds had disappeared in October 1883, when Sitting Bull and his band killed the last 1,200 on the Great Sioux Reservation in Dakota Territory.

But, chasing rumors, Hornaday set forth by train with two museum assistants for the little cow town of Miles City, Montana on May 6, arriving after four days.

Since his journey was a government project, Hornaday had some clout, and managed to pry loose a few soldiers from nearby Fort Keogh to come along on a buffalo hunt.

All inquiries, both in Miles City and at Fort Keogh, two miles distant, got the same reply, “There are no buffalo anymore and you can’t get any anywhere!”

However, one distant rancher on the Little Dry Creek sent a message that was still a chance to find a few buffalo around the Big Dry.

Five days later their party crossed the Yellowstone River and headed up Sunday Creek to the northwest, where a few survivors might still be living farther north in the rough badlands country known as the Missouri River Brakes.

By this time they had an escort of a Sergeant and four soldiers from Fort Keogh, plus a cook, teamster, wagon, and six-mule team. They purchased two saddle horses for hunting.

His party rode horseback more than a hundred miles farther, deep into the most rugged country they had ever seen.

There they had a series of hunting adventures unlike any other, as detailed in Hornaday’s government report, later published as his despairing book on how the “extinction” came about.

They finally found and captured a lone buffalo calf, which exhausted, had been unable to catch up with its mother. But they never found the herd it came from.

On the 10th day they found a couple of bulls. They shot one and realized he was shedding his winter coat—leaving his hide so tattered and seedy looking it could not be mounted.

The Hornaday party arrived in May and hunted the remote badlands northwest of Miles City. But when they did shoot a bull, its hide was so tattered and seedy looking they decided to return in September for hides in prime winter condition. Credit NPS, J Schmidt, 1977.

They decided to wait till fall for hides in prime winter condition.

After beseeching local ranchers to spare their intended targets, they took the live calf and returned to Washington.

In late September they returned to the same remote badlands, some 135 miles northwest of Miles City.

“Wild and rugged butte country, its sides scored by intricate systems of great yawning ravines and hollows, steep-sided and very deep and bad lands of the worst description.

“Such as persecuted game loves to seek shelter in,” wrote Hornaday.

In two months of hard riding they found a few small bands of extremely wild stragglers—a lone buffalo bull here, two or three cows with calves there. Seven in one bunch.

By this time they had 10 saddle horses and the help of a few more soldiers from Ft. Keogh.

Splitting up, they rode 25 miles or more each day in different directions.

Searching out “the heads of those great ravines around the High Divide . . . where the buffalo were in the habit of hiding,” they eventually killed 22 buffalo—bulls, cows and calves.

Not the 80 carcasses Hornaday had hoped for, but a raging November blizzard with bitter cold cut short their hunt.

Hornaday felt some pride at the big bull he shot himself.

“A prize! A truly magnificent specimen. A stub-horn bull about 11 years old. His hair in remarkably fine condition, being long, fine, thick and well colored—16 inches in length in his frontlet.”

His bull stood a full six feet tall when they added the four-inch-long hair on the hump—standing two inches taller than their next largest bull.

He was nine-feet-two inches, head to tail. In circumference, eight-foot-four around the chest just behind the foreleg.

The bull had been shot several times before. Within the carcass he carried four old bullets of various sizes—as did nearly every bull they killed in those hidden canyons.

Cover of Hornaday’s book Campfires in the Canadian Rockies. This is the story of a trip he made in 1905 with John M. Phillips to high mountain crags and ledges in the Canadian Rockies. They spent more than a month studying, as no trained naturalists ever had before, the habits of the mountain goat at close range. Phillips photographed them, he said “under conditions of utmost peril.” Photo by JM Phillips.

Returning to Washington, Hornaday and his assistants set to work.

After a full year they unveiled their masterpiece.

There in a huge glass case, visitors to the Smithsonian Museum viewed an enchanting scene.

The grouping of six buffalo in an authentic Montana setting, included Hornaday’s prize stub-horn bull.

The Washington Star described the exhibit on March 10, 1888:

A little bit of Montana—a small square patch from the wildest part of the wild West—has

been transferred to the National Museum. . .The hummocky prairie, the buffalo-grass, the sagebrush, and the buffalo.

It is as though a little group of buffalo that have come to drink at a pool had been suddenly struck motionless by some magic spell, each in a natural attitude, and then the section of prairie, pool, buffalo, and all had been carefully cut out and brought to the National Museum.

A triumph of the taxidermist’s art!

It was a sight Hornaday feared no one would ever see alive again.

He hid a message voicing his despair in a small sealed metal box in the Montana dirt of the display.

Discovered nearly 75 years later when the exhibit was moved to Montana, curators read Hornaday’s heartfelt plea:

My illustrious Successor

Enclosed please find a brief and truthful account of the capture of the specimens which compose this group.

When I am dust and ashes, I beg you to protect these specimens from deterioration and destruction.

W.T. Hornaday

Chief Taxidermist, March 7, 1888

But Hornaday was not finished. He still had his official report to write: (ital) The Extermination of the American Bison, for the National Museum’s 1887 annual report. It was reprinted as a book in 1889.

George Bird Grinnell Joins the Cause

George Bird Grinnell and hiking party on Grinnell Glacier, Glacier National Park, MT. Credit Morton Elrod, University of Montana, Mansfield Library.

George Bird Grinnell joined the cause of saving buffalo early.

Like fellow conservationists Hornaday and Theodore Roosevelt, Grinnell had a special interest in the west—where he made more than 40 trips from his New York headquarters.

Like them he had hunted buffalo, and in fact, joined the Pawnee’s last great buffalo hunt in 1872, at the age of 22, while still in college.

That year in August Grinnell and a friend took the train to what they considered an exciting new travel destination: Nebraska.

The Pawnee were living on a small reservation along Nebraska’s Loup River. Twice a year, the army allowed the tribe to travel south to hunt buffalo in their historic Kansas hunting grounds.

These “hunts of the Indians [had] been described to me with a graphic eloquence that filled me with enthusiasm as I listened to the recital, and I determined that if ever the opportunity offered I would take part in one,” wrote Grinnell.

With the help of a guide, they found the Pawnee hunting village of 200 lodges spread across the prairie.

The head chief received them warmly telling them the hunt so far, had not been successful.

“But tomorrow,” he promised, “a grand surround will be made.” His young scouts had reported a large herd about 20 miles away.

“Here were 800 warriors, stark naked, and mounted on naked animals,” said Grinnell. “A strip of rawhide, or a lariat, knotted about the lower jaw, was all their horses’ furniture.

“Among all these men there was not a gun nor a pistol, nor any indication that they had ever met with the white men . . . Their bows and arrows they held in their hands.”

Grinnell and 800 hunters thundered across the Kansas plains.

He marveled at the skill of the bareback riders, so perfectly in tune with their horses, that the plains appeared to be “peopled with Centaurs.”

Despite the excitement of the hunters, tight discipline governed their advance. At regular intervals in the front of the procession rode the “Pawnee Police,” whose authority during the hunt was absolute.

Much was at stake. The food supply of the tribe for the next six months would be determined in the moments about to unfold.

Ten miles from camp, the lead riders, Grinnell among them, carefully crested a high bluff.

“I see on the prairie four or five miles away clusters of dark spots that I know must be the buffalo.

“Close now, the hunters change course, using the line of bluffs to conceal their advance.”

Finally, only a single ridgeline separated the mass of hunters from the mass of their prey.

“The place could not have been more favorable for a surround had it been chosen for the purpose,” according to Grinnell.

The terrain before them consisted of an open plain, two miles wide, surrounded by high bluffs.

“At least a thousand buffalo were lying down in the midst of this amphitheater.”

In a classic surround, Indians encircled the herd before the great charge. In this hunt, though, they would employ a variant of the strategy.

“All 800 hunters would ride into the herd from the same side. The objective was for the fastest riders to pass all the way through the herd, then turn back to face it.

Grinnell said great clouds of dust quickly filled the air, along with flying pebbles and clods kicked up by fleeing hooves. He realized that some buffalo were now coming back—directly at him. The herd had been turned. CM Russell painting.

“If successful, the herd too would turn—into the charging bulk of the hunters.”

Behind the ridgeline, the hunters assembled in a long, crescent-shaped formation. Then over the hill they rode.

“[W]hen we are within half a mile of the ruminating herd a few rise to their feet and soon all spring up and stare at us for a few seconds.

“Then down go their heads and in a dense mass they rush off toward the bluffs.

“The leader of the Pawnee Police gave a cry, “Lo?-ah!”

“Like an arrow from a bow each horse darted forward,” recalled Grinnell. “Now all restraint was removed, and each man might do his best.”

Grinnell, who had only one horse, soon fell behind the Indians on fresh mounts. Great clouds of dust quickly filled the air, along with flying pebbles and clods kicked up by fleeing hooves.

As he galloped forward, Grinnell could just make out the fastest riders, disappearing into the herd. Soon he could no longer see the ground, relying completely on his horse to navigate the field, aware that falling could mean death.

Halfway across the valley, Grinnell realized that some buffalo were now coming back—directly at him. The herd had been turned.

“I soon found myself in the midst of a throng of buffalo, horses and Indians.”

Grinnell began shooting, “and to some purpose.”

Two-thousand-pound animals tumbled and skidded to the earth around him. Shooting from a galloping horse required a skilled mount, steady hands, and even steadier nerve.

Riders attempted to come alongside a running buffalo, aiming behind the shoulder. It was difficult and dangerous.

“The scene that we now beheld was such as might have been witnessed here a hundred years ago. It is one that can never be seen again.”

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Grinnell lived in Audubon Park as a young man, on what was previously the estate of John James Audubon. His school, conducted by Madame Audubon likely encouraged his interest in the natural world.

As a graduate student and naturalist he rode with General Custer’s 1874 Black Hills expedition. The next year he went with Col. William Ludlow’s expedition to Yellowstone Park, and wrote a scathing report on the poaching of buffalo, deer, elk and antelope that was going on there.

While still a student, George Bird Grinnell went with Col. Ludlow’s expedition to Yellowstone Park and wrote a scathing document relating the disastrous poaching of buffalo and other wildlife, attached to Ludlow’s report.

Grinnell graduated from Yale University in 1870, earned a PhD in 1880 and became an anthropologist, historian, naturalist and prolific writer.

In 1876 Grinnell became editor of Field and Stream magazine and remained there as senior editor and publisher for 35 years. This gave him an excellent platform for his writings on conservation and environmental issues.

He took hunting trips with the well-known guide James Willard Schultz. During a 1885 visit they hiked over the St. Mary Lakes region, naming many of the features in what is now Glacier National Park in Montana—including Grinnell Glacier.

About this area he wrote:

“Far away in Montana, hidden from view by clustering mountain-peaks, lies an unmapped northwestern corner—the Crown of the Continent.

“The water from the crusted snowdrift which caps the peak of a lofty mountain there trickles into tiny rills, which hurry along north, south, east and west, and growing to rivers, at last pour their currents into three seas.

“From this mountain-peak the Pacific and the Arctic oceans and the Gulf of Mexico receive each its tribute. Here is a land of striking scenery.

“There is a solitude, or perhaps a solemnity, in the few hours that precede the dawn of day which is unlike that of any others in the 24, and which I cannot explain or account for. Thoughts come to me at this time that I never have at any other.”

But he also wrote, “We are a water-drinking people and we are allowing every brook to be defiled.”

Hornaday Voices his Despair

In his 1889 book, The Extermination of the American Bison, Hornaday regarded the buffalo extinction as inevitable.

“There is no reason to hope that a single wild and unprotected individual will remain alive 10 years hence,” he wrote.

“And in a few more years, when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton shall have been picked up,” wrote Hornaday. “Nothing will remain of him save his old, well-worn trails along the water courses, a few museum specimens and regret for his fate.” NPS.

“The nearer the species approaches complete extermination, the more eagerly are the wretched fugitives pursued to the death whenever found.”

His official count of the surviving buffalo in 1889 totaled only 1,091 head for all of North America. Half of that total he credited to “very old rumors” of 550 wood buffalo in northern Canada.

That was likely an exaggeration, he admitted. But, “We will gladly accept it.”

However even this number was destined to drop lower. The lowest official number fell to 800 in 1895, according to the count of Canadian historian Ernest Thompson Seton.

The 200 counted in Yellowstone Park had dropped to a low of only 23, as the herd was nearly annihilated by hide hunters lurking at its borders and poachers within, according to the National Park Service.

Hornaday voiced his despair.

“If the majority of the people of America feel that so long as there is any game alive there must be an annual two months or four months open season for its slaughter, then assuredly we soon will have a game-less continent!” he said.

“The wild buffalo is practically gone forever.

“And in a few more years, when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton shall have been picked up and shipped East for commercial uses, nothing will remain of him save his old, well-worn trails along the water courses, a few museum specimens and regret for his fate.”

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog