Interview with Marko Manoukian, Phillips County Extension Agent, Malta, Montana.

In our BLOG of June 23, 2020, we published “American Serengeti—What is going on in Montana?,” which discusses the enormous wildlife project that is shaking the foundations of community development and progress in Phillips County, Montana, and Malta, its county seat, and nearby communities.

The American Prairie Reserve—APR, or simply the Prairie Reserve–on the upper Missouri River is a plan to develop a huge grazing unit—the largest nature reserve in the continental United States.

American Prairie Reserve buffalo graze along Telegraph Creek on Sun Prairie. Photo by APR, Dennis Lingohr.

On this land APR aims to turn back the clock and restore the wildlife that roamed here two centuries ago, along with its large predators—grizzly bears, packs of wolves, mountain lions—and great herds of wild buffalo.

The idea grew from casual roots when this Montana area was “discovered” in 2000 by a group of environmentalists who proclaimed it critical for preserving grassland biodiversity.

One year later, in Silicon Valley, San Francisco, a member of that group, a biologist named Curt Freese, teamed up with a Montana native named Sean Gerrity and together they formed the American Prairie Reserve (APR).

Gerrity, a Silicon Valley consultant, says the idea was to “move fast and be nimble,” in the manner of high-tech start-ups.

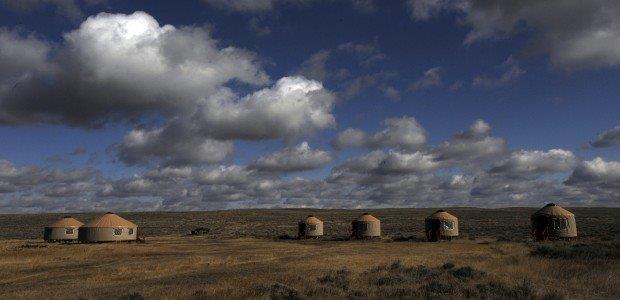

They would remove the thousands of cattle grazing public land, stock it with 10,000 buffalo, tear out divider fences, restore native vegetation, and add missing wildlife in a pristine natural setting. This would be much appreciated by their wealthy donors from all over the world who could visit occasionally, staying in opulent yurts.

In the 19 years since, the Prairie Reserve group has moved ahead, raising $160 million in private donations, nearly all of it from out-of-state high-tech and business entrepreneurs across the U.S. and Europe.

They have acquired 30 properties—cattle ranches—totaling 104,000 acres. To this they added about three times that—more than 300,000 acres—in grazing leases on adjacent federal and state land—as owners are allowed when they purchase land with grazing rights.

Plans are to purchase about 20 more ranches.

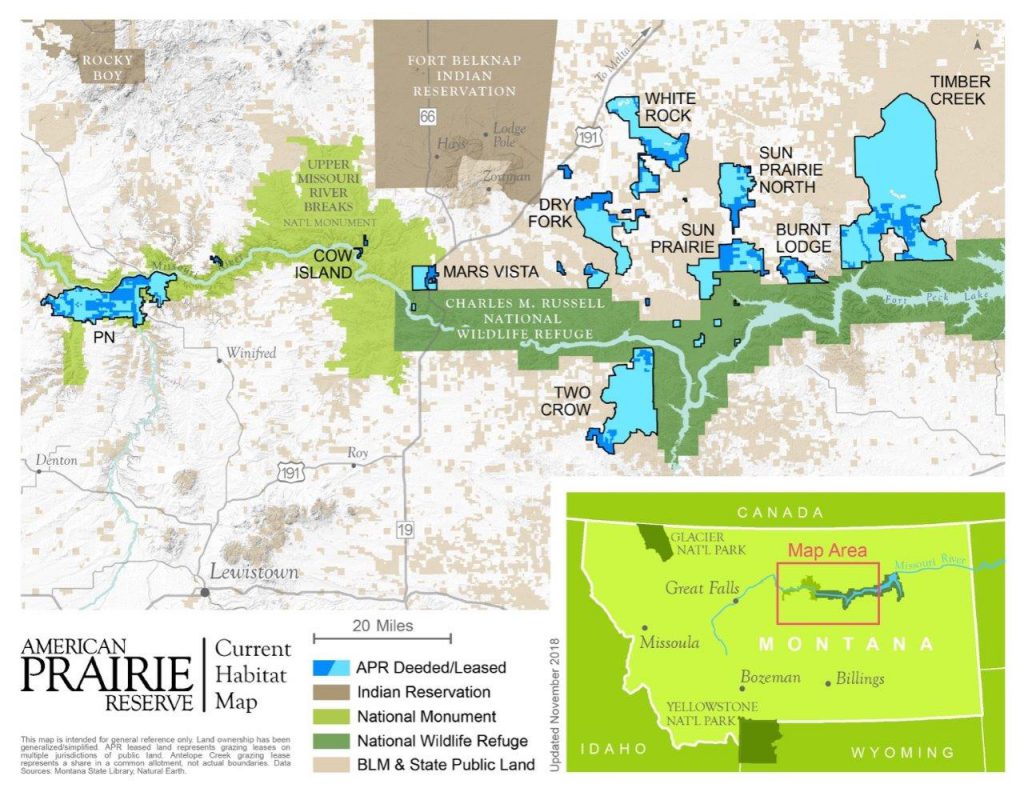

In this American Prairie map of the proposed area, blue areas depict lands purchased and leased by the American Prairie Reserve in the last 19 years. The plan is to connect these with Federal lands, including the Charlie Russell National Wildlife Refuge (dark green) and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument (light green) and other state and federal and perhaps Indian lands (brown). APR Map.

The properties purchased are all strategically located near two federally protected areas: the 1.1 million-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the 377,000-acre Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, according to National Geographic (Feb.2020, p69-89), which partners with Prairie Reserve in the Last Wild Places initiative. Other Federal and State lands intersect as well. Most of these lands are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a division of the Department of Interior (DOT).

Other environmentalists, such as The Nature Conservancy, have long purchased lands for conservation, but none have done it in the large-scale APR proposes, according to National Geographic. Few have had the ambition as the Prairie Reserve does, of retaining long-term ownership and management authority of that land as well as adjoining publicly-owned lands.

Needless to say, cattle ranchers and many local townspeople—who have been watching the inevitable disintegration of formerly close communities, as one rancher after another sells out to APR, and families and businesses leave—are not pleased with what is happening.

We invited Marko Manoukian, Phillips County Extension Agent, of Malta, Montana, representing the Philllips County Livestock Association, to give us the cattle ranchers side of this Montana controversy.

Below is our interview with Marko Manoukian.

Marko Manoukian, Phillips County Extension Agent, of Malta, Montana, surveys the irrigation system in his county. He represents the Philllips County Livestock Association in presenting the cattle ranchers side of Montana controversy over APR. Photo submitted by M Manoukian.

Francie Berg: What is the American Prairie Reserve (APR) doing that upsets the local ranchers so much?

Marko Manoukian: Principally, they are crowding out the ability of ranchers to compete economically for agricultural land—in this case grazing land.

Because APR pays a premium for the property—more than a neighboring rancher could pay off with cows—this doesn’t allow for young people to come back and be engaged in livestock production.

Francie: Do you disagree with APR’s statement that they pay the regular, going price for land?

Marko: Correct, principally because, they are a 501C3 charitable organization so they get tax-free dollars to compete.

The tax code under charity is reserved for those things related to health or education. APR getting that designation is far outside the scope of the tax code.

But they got it somehow.

Francie: So they have already got from the BLM what they want?

Marko: Well, competition for the land is one issue.

Malta is losing its population of 2,000, say ranchers. They worry that each ranch APR acquires is one lost to the community, draining taxes from the county treasury, children from schools, and business from stores. Photo by maltachamber.com.

Another issue is that they’ve made application to BLM for year-around grazing and to alter the fence perimeter.

Neighboring ranchers or permitees are required to make application through the BLM and have been denied those things.

Francie: Denied what?

Marko: Year-around grazing and fence altercation. There’s supposed to be an environment assessment made by the BLM to be approved before any fences are changed.

None of that has happened—and I suppose in Phillips County alone they’ve probably altered 100 miles of BLM perimeter fence already.

Some neighboring operators are angry because now the fences are electric and that’s a hazard for them and their cattle.

Francie: Why is that a hazard?

Marko: Well as a neighboring rancher, yes it is. Because you’re not in charge of energizing the fence. They are.

So if your cow somehow got across the fence you might not know how to turn the fence off to get to the other side.

This would be the same for recreation, crawling around hunting—hunters may not know how to turn the fence off or even know that it is electric before they get zapped.

Francie: You’re saying electric fences are a problem for recreation?

Marko: Yes. Electric fences are a limitation to recreation.

Francie: The BLM land is supposed to be open for recreation, isn’t it?

Hand Lettered sign objects to federal decisions overriding local input. Photo by Shawn Regan.

Marko: Correct. That’s not multiple use. We’ve argued that electric fence is not multiple use.

Francie: So you think the BLM is treating the cattle ranchers unfairly.

Marko: Yes, they are.

Francie: And what course do the ranchers have?

Marko: Two actions that ranchers have taken.

BLM has said we’re going to change the allotment from cattle to bison. And the ranchers have objected to that. One is to object to change grazing from cattle to bison.

Francie: Can they just change it without consulting anyone?

Marko: True. Well they haven’t changed it yet. But early on the neighboring permitees could see that there is favoritism going on. So they’ve challenged everything that BLM has done.

Francie: You’ve done this in a legal way?

Marko: Yep. We’ve hired an attorney to review and represent us in that process.

I think there are 5 allotments now. Originally it was 18 allotments that they wanted to change to year-around grazing and bison grazing only. But now they have requested permits for just 5 allotments.

Francie: The ranchers are challenging this?

Marko: Yep.

Francie: What will happen next?

Marko: Eventually BLM will provide a document suggesting the best management alternatives they see under that request. So we’re just waiting for that environmental assessment document to come forward. Or they can deny the request all together.

Francie: So they can deny APR s request—or your request?

Marko: Yes, either of them.

So then the other action the livestock operators have taken. The citizens of the county have passed an ordinance that bison must be handled like livestock.

The citizens have said all bison have to be managed like cattle. This means owners have to do disease testing and some identification of their animals.

Signs in Malta oppose bison ranging free. “What APR really wants is a takeover of Federal land and control of how it’s managed,” says Deanna Robbins, a rancher in Roy.

But APR has asked for a variance from that ordinance So we’re working through that process.

Francie: I also noticed—BLM is saying that the bison are fine with just 1 single fence around the outside. In our area BLM is telling the ranchers they have to build inner dividing fences and rotate their cattle quite frequently.

Marko: Yes, all BLM pemitees are required to rotate their animals on BLM Land.

It’s the biggest change that BLM has taken on over the course of its existence. And now they want to go back to one giant pasture and keep the same animals in there all year around.

Francie: I read that the APR goal is to get 10,000 bison in their one large, single pasture. Do you think 10,000 would be fully stocked for that amount of land?

Marko: Yes, that’s more than a full load.

Francie: So won’t they graze it down even faster if they do it without rotation?

Marko: Yes, that’s our claim.

Francie: Montana is a big producer of cattle, right? So if this happens to that big chunk of grazing land, it will cut Montana’s beef production. Any speculation on this?

Marko: Oh, Yes. APR is planning on taking productive land and turning it into no production. That hurts our economy. Both regional and local economy are impacted. Also they are impacted because the APR operations aren’t buying fuel, fertilizer, net wrap and tires.

Francie: And it seems kind of deceptive that these people are outsiders from Silicon Valley, but making a case that they are Montanans, even placing their so-called national headquarters in Bozeman.

Marko: That’s their story, yes. Well some of them are, I guess.

Francie: What about the luxury yurts they are advertising for their donors? Are they available for use by everyone?

Marko: Well, it does appear that the preserve is used mostly by the upper class. Some of their packages are priced at $2,500 occupancy per person—that doesn’t include their traveling to get here.

Yurts on the plains may look as simple as granaries. But according to photos in Prairie Reserve’s advertising material the luxury is all inside. They are draped in opulent hangings and furnished with exotic items for lavish living in the manner of Arab tents awaiting Lawrence of Arabia. David Grubbs, Billings Gazette.

Francie: What about local people? Do they have a lower price for ordinary people to stay overnight?

Marko: I don’t know if they advertise a local or lower price.

Francie: They say they don’t charge people to come onto their lands. Is it free to come into their refuges?

Marko: They don’t have any legal authority to regulate how people enter the BLM land, which is the majority of their holdings. I’m suspicious that on their deeded land—some people may be charged and some not.

Francie: Right now do they only run bison on their purchased land, not BLM lands?

Marko: I believe they do have 1 BLM permit licensed for bison, but no other bison as yet on BLM land.

Francie: Sounds as if they are trying to totally change the livestock from cattle to bison. I also heard a complaint that this will give APR long-term power about how the bison pastures are handled.

Marko: I don’t know that they’re going to have a lot of repeat customers to come out to the prairie. We haven’t had rain on the prairie for most of the summer. So the grasshoppers are horrible.

I know there are going to be ranchers who have to adjust the livestock they have on BLM land.

Francie: So how are they going to adjust the bison numbers in a dry year if they already have too many head? If there are too many grasshoppers and too little moisture—have they planned for that?

Marko: No they don’t plan for those kinds of environmental impacts.

Like in 2010 and 2011 we had 100 inches of snow. APR didn’t have any hay. The buffalo broke out. Left their property, traveled a long ways, and had to be brought back by helicopter.

Francie: Why did they break out?

Marko: The buffalo broke out because they were hungry!

Hopefully long-term BLM will stick to the rules.

Francie: Do you have a good case?

Marko: I think we do. And hopefully the rules of management of our public land will hold. Congress hasn’t overturned the Taylor Grazing Act. So if they stick to the rules, they’ll have to make application and not be allowed to run free-range.

Francie: So they won’t be able to just run freely under 1 big fence. You’re saying that most of the cattle ranchers agree on this?

Marko: Yes—they would be against changing the rules.

Francie: Doesn’t APR plan to link all this land with just 1 perimeter fence around it?

Marko: That’s their theory. But they’re pretty well spread across our county and across the river and they’re not necessarily connected.

DOI Presents 10-year Plan for Bison

Geese fly over a semi truck emblazoned with a banner promoting private land ownership in Lewistown on Thursday, Jan. 24. Across the street the American Prairie Reserve was holding a public conference for agricultural producers on Living with Wildlife. Photo Bret French, Billings Gazette.

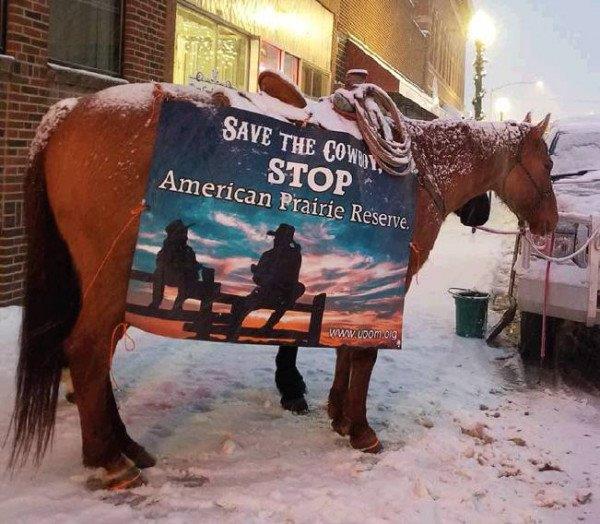

Francie: It’s interesting, the “Save the Cowboy” signs we see around your county and other counties close by. I think their point is quite clear—a lot of local people don’t like what they are seeing.

However, I see that the Department of the Interior (DOI) of which BLM and the government grazing lands are a part, has a new 10-year plan concerning Bison.

That powerful department—DOI which governs one eighth of the land mass of the United States—recently announced their commitment to establish and maintain large, wide-ranging bison herds on “appropriate large landscapes.”

Their 10-year plan, called the Bison Conservation Initiative, is a new cooperative program that will coordinate conservation strategies and approaches for the wild American Bison over the next 10 years. They mention working with tribal herds in North and South Dakota.

What do you think of that, Marko?

Marko: In Interior’s press release I don’t see any mention of tribes in Montana, so hard to say what impact this will have in other states.

With the smallest cow herds in the US at least since 1950 one would wonder why the US government would help tribes remove more cattle. But if the tribes want to do that just on tribal lands that would be ok, of course.

Francie: Right, both the projects mentioned in the press release are quite limited, and have to do with increasing tribal buffalo herds and genetics of the Theodore Roosevelt Park herd.

On the other hand—when we look at DOI’s 10-year goals organized around five central themes,

it sounds as if they might have wider plans than that.

Here are DOI’s announced 10-year goals:

1.Wild, Healthy Bison Herds: A commitment to conserve bison as healthy wildlife

2.Genetic Conservation: A commitment to an interagency, science-based approach to support genetic diversity across DOI bison conservation herds

3.Shared Stewardship: A commitment to shared stewardship of wild bison in cooperation with states, tribes and other stakeholders

4.Ecological Restoration: A commitment to establish and maintain large, wide-ranging bison herds on appropriate large landscapes where their role as ecosystem engineers shape healthy and diverse ecological communities

5.Cultural Restoration: A commitment to restore cultural connections to honor and promote the unique status of bison as an American icon for all people (Department of Interior Press Release 5/7/2020)

“Ecological Restoration and establishing and maintaining large, wide-ranging bison herds” sounds eerily like what the Prairie Reserve is trying to do.

Yet if that commitment is to be tempered by the “Shared Stewardship,” pledge to cooperate with “states, tribes and other stakeholders,” surely DOI will not participate in deliberate breaking up of close communities against the desires of local residents.

When there is a strong cultural backlash from 100-year residents—as there is from Malta and the Phillips County cattle ranchers—certainly that needs to be considered.

DOI and BLM when acting locally will surely recognize heavy-handedness when they participate in it.

If they think they can override local protests, the “Save the Cowboy” signs make the issues clear. Montana ranchers are making them plain with both lawyers and hand-made signs.

A pair of horses on Lewistown’s Main Street helped spread a message of support for cowboys and opposition to the American Prairie Reserve during the Living With Wildlife Conference last winter, for which the APR was a co-sponsor. Photo by Danica Rutten.

It seems that DOI and BLM need to back off and recognize that the arrogance of these environmental outsiders does not sit well with Montanans.

Their heavy-handedness can in no way be called “Shared Stewardship” with “states and other stakeholders” even when they can “move fast and be nimble,” in the words of Sean Gerrity.

Indeed, maybe 10,000 sometimes-hungry buffalo under one single electric-fenced pasture is not such a lofty goal, after all.

Right DOI? And if you’ve been thinking so, please tell us why.

What gives them—and you—the right to destroy living communities?

Maybe it only proves the arrogance and pig-headedness of those who have “discovered” this little gem of 100 years of shared conservation efforts at such a late date?

For more on how DOI is working “to improve the conservation and management of bison,” contact Interior_Press@ios.doi.gov)

Francie M Berg

Author of the Buffalo Tales &Trails blog